Three years ago, the strangled body of a troubled Bloomington woman was discovered in a cornfield. With no arrests and no answers, Crystal Grubb’s family has been left to wonder what happened. Every day, they try to piece together who Crystal was and who

Three years ago, the strangled body of a troubled Bloomington woman was discovered in a cornfield. With no arrests and no answers, Crystal Grubb’s family has been left to wonder what happened. Every day, they try to piece together who Crystal was and who she might have become — in a town that has forgotten her name.

The 9-year-old sinks into the couch.

The tidy mobile home where Abby lives with her father and younger sister is quiet. Holding some crayons, she focuses on what will be the first entry inside her new pink journal — pink, like her alarm clock and makeup kit. Don’t call it a diary, she says, because it’s not.

On the first page, the third-grader carefully prints her name. On the second, she draws a smiling stick figure, a woman with an orange dress and a wave of yellow hair. The woman holds out her arms under a bright sun.

With her lime-green crayon, Abby draws an arrow pointing to the figure. Then she writes:

“My mom.”

After the murder, it’s how Abby remembers her.

***

Three years ago, Crystal Grubb’s body was discovered in a cornfield outside Bloomington. The 29-year-old Bloomington woman had been strangled to death. Her body, naked except for her underwear, laid among the stalks for 13 days before it was spotted by a farmer.

In the early weeks of the investigation, the detectives named persons of interest, but the case remains unsolved.

To those who knew her, Crystal remains a mystery. Her daughter Abby remembers her as a woman smiling in the sun. But the adults in her family recall someone far more complex. Long before she was reported missing, Crystal began disappearing before their eyes.

Crystal lived on the fringes most of her life. In her high school years, she struggled to remain motivated. She lost interest in school and turned to drugs. She dropped out when she was 16 and moved out of her parents’ home.

In her final years, a meth addiction and erratic behavior consumed Crystal. She spent her days alone in bed and went out with friends at night.

During the last decade, the shy-looking woman who wore her blonde hair in a tight bun and loved to play with kids began to fade.

Photos through the last few years of her life show a clear descent — her hair usually drawn back in a tangled ponytail, the soft features of her face became distorted, scratched and stretched. She didn’t have a job, so she sometimes used rent money from her boyfriend to pay for drugs.

In the long silence since her murder, her family has tried to remember who she was beyond the broken promises and the daily chaos that was her life.

“There ain’t nobody in this world that’s perfect,” says her mother, Janice Grubb.

Her family wants to remember the person she was before the addiction took over. The young woman who talked of becoming a nurse, who grew shy in the presence of a camera, who kept a collection of ceramic frogs. The mother who would play Candy Land with her daughters and hold them in her lap as they opened Christmas presents.

At night, before Abby would drift asleep, Crystal would sing their favorite song — Miley Cyrus’ “The Climb.”

“Every step I’m taking / Every move I make feels / Lost with no direction / My faith is shaking.”

Abby knows her mom died, but she doesn’t know the details. Abby understands that something went wrong, but she doesn’t know that the smiling woman she drew in her journal suffered from addiction. She does not realize that sometimes her mom wasn’t much of a mom at all.

***

On the afternoon of Sept. 18, 2010, Crystal went into the woods with three friends and never came back.

Most thought she’d return, until her body was found.

Crystal’s name — for the short time it was periodically splashed across headlines — was forgotten within months of her body being uncovered. Her face never blanketed a billboard. She was never the focus of community fundraising or volunteer efforts. In quiet, some say she was even fated to meet her violent end.

Her mother refuses to entertain the thought as she vigorously pursues her daughter’s case.

“This town’s all messed up because you can’t get justice,” Janice says.

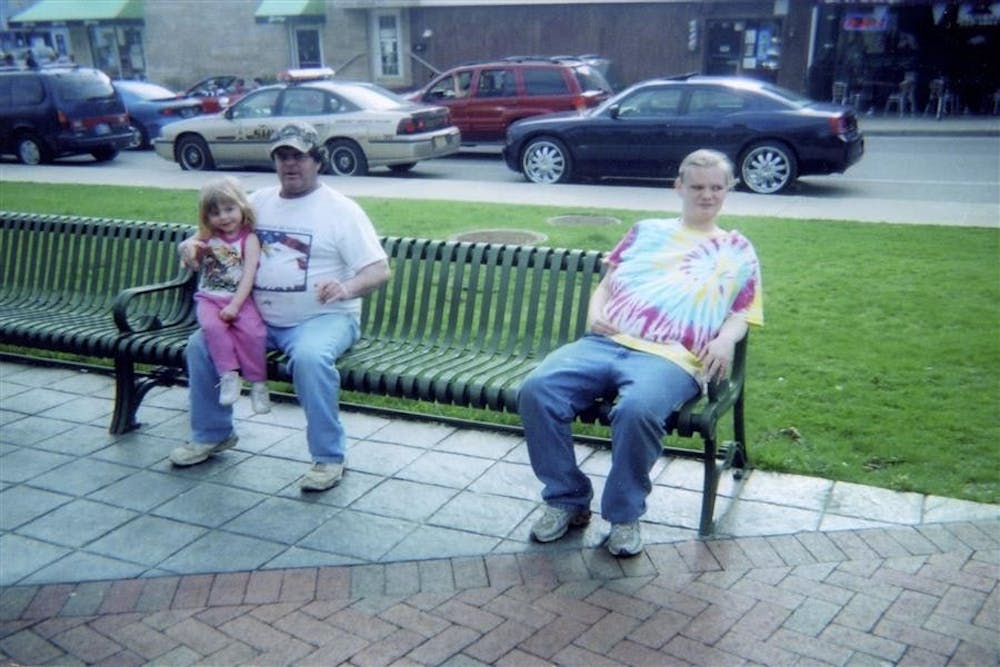

A family album tells the story of Crystal as a woman who usually smiled only when she held her daughters, Abby and Rosey. In the background of one photo, a sign reading “born to be wild” hangs behind Crystal.

She so deeply cared for others, Janice says, and was seldom alone. Crystal was constantly coming and going. But Janice could always expect a call when she’d take off without notice.

“Mom, I’m OK. You worry too much,” Crystal would say before hanging up. “I love you.”

In 2003, Crystal met Tony Williams. The day after they met, Crystal was sick with the flu. So Tony visited her with Tylenol and a can of chicken noodle soup. He loved that she wanted to be with him.

Tony was 21 years older than Crystal, and he tried his best to compensate for the age difference.

“She was young and pretty, and I was lonely,” he says. “We had fun together. I wanted someone to do things with.”

They would spend their days riding motorcycles, taking trips to the lake and playing Frisbee.

“I just tried to act young,” he says. “I was almost a father figure, showing her different things, teaching her about life.”

She was eccentric and unpredictable. He kept to himself.

She liked rap music. He liked rock ’n’ roll.

He knew about her drug use and wild streak, and for a while joined her in that life. They’d spend nights together sipping beer and getting high. But Tony couldn’t keep up.

They had two children together, Abby and Rosey, but never married. She continued using.

“I guess I thought I could save her,” says Tony, now 53.

For five years, the relationship dragged on. Of all their years together, he says, just the first stands out as a good one. They spent the others attempting to salvage their relationship for the two girls. It didn’t work.

In the mornings, Tony would leave for his tree-trimming job, with Crystal still asleep, exhausted from the night before. It wasn’t uncommon for her to get up in the dead of night and leave without saying a word.

Most days, he’d come home from his job by 4 p.m., and the home looked as it did when he left in the morning. Frustrated, he would return to the tower of dishes stacked precariously in the sink.

Eventually, Crystal’s lifestyle was too much for Tony. The kids stayed with him.

When they separated for good, Crystal kept in touch with the girls but struggled to maintain a consistent relationship with them.

“She was there on her convenience,” Tony says.

She could visit, but she had no home to welcome them to — no single beds or pink alarm clocks, no Justin Bieber posters on the wall like the one in Abby’s room. Nothing. She’d sleep on couches or at her new boyfriend’s.

In her last few years alive, Crystal’s presence in Tony and the girls’ lives grew more and more infrequent. But maybe, Tony says, that was for the best. It was slow and gradual.

And then she was gone.

Today, Tony is still trying to make sense of what happened. With the girls at school, he leans back in his armchair in the living room and takes in the quiet.

“I wish I could tell you 100 great things about her, but they just aren’t there, honestly,” Tony says. “She liked to play with the kids and games, but I guess she liked drugs better.”

***

The days before Crystal disappeared stick out in her mother’s mind. Janice was sipping coffee with her sister and husband when Crystal stopped by with her new boyfriend, Adrian Henley, to drop off some dirty laundry.

Janice heard them before she saw them. Crystal and Henley were screaming at each other as they stepped out of their car. The two had been dating since Crystal’s split with Tony.

“Here they come, fighting again,” Janice’s sister said.

Crystal stormed through the door, stopping in front of the table. Henley followed close behind.

Janice says she never liked Henley. In the past, she and Crystal would go back and forth in screaming matches because Janice wouldn’t allow him to stay in the house.

Crystal and Henley were always fighting. She’d follow him around like a lost puppy, Janice says, doing whatever he told her.

“Something’s gonna happen to me,” Crystal told them that day as they entered her mother’s kitchen, “and nobody’s gonna goddamn know.”

Two days after she came screaming into Janice’s house, Crystal, Henley and two other men drove to Bean Blossom Creek.

Vast and relatively secluded, the woods are a hideaway along a thin stretch of road west of Route 37.

When Crystal never returned, her family grew suspicious of the men she was with. The three men, Henley, Alvin Fry and John Sergent, eventually told detectives that they had been cooking meth in the woods with Crystal and that she had become angry and stormed off alone.

Almost two days after Crystal left for the woods, Janice grew worried. Crystal had never picked up the laundry she’d dropped off.

At first, Tony wasn’t concerned. Maybe she’d just run off, he thought. But then more days went by, and she wasn’t calling the girls. She’d never been away on a partying binge this long.

By the end of the second day, Crystal’s mother and sister reported her missing. Police searched the woods and surrounding areas by foot. The family wanted to do more. So they gathered what little money they had and taped Xerox copies of Crystal’s face around the city.

A week passed. Then almost two.

On the 13th day, Crystal’s body was found. The three men who were dubbed persons of interest maintained their innocence. Each of the men she was with has changed their version of events to police at least once.

They were brought up on drug-related charges, and Crystal’s driver’s license was found on Henley.

The day after the body was discovered, investigators asked Crystal’s mother to come to the sheriff’s office to provide an oral swab.

As she sat in the station, Janice’s thoughts raced.

Could it actually be Crystal? If so, what had happened? Nobody could tell her anything.

“Sorry,” said one of the detectives, “this is my first homicide.”

***

When the news reached Tony, he drove to Brown County where the girls were with his mother for the day. When he arrived, the sounds of the girls playing inside greeted him at the door.

Tony sat them down and explained that mommy was gone. That she was dead, her body found in a cornfield. He hardly knew what had happened himself, so he spared the details as Abby began to cry.

Maybe mommy had a heart attack, he told the girls. Maybe she had fallen and hit her head.

From that point, the girls were raised to believe their mother died of a heart attack.

Before Crystal disappeared, she’d remembered Abby’s sixth birthday and bought her a card. A Miley Cyrus card.

Tony was conflicted. He waited for weeks after Crystal’s body was found to give Abby the card. He feared the psychological implications of Abby associating her mother’s death with her birthday. Crystal had not yet written anything inside the card, leaving Tony to decide what their oldest daughter needed to hear.

There was no hesitation when he opened the card, trying his best to mask his own handwriting.

“Love, mommy,” he wrote.

Later on, Abby opened the Miley Cyrus card, and her favorite song began to play.

“There’s always gonna be another mountain / I’m always gonna wanna make it move / Always gonna be an uphill battle.”

***

Today, Janice sits on her bed, scrolling through the memorial page she made on Facebook. She posts another plea, praying that this time, someone might actually come forward.

On some afternoons, she relaxes by sketching ideas for memorial posters. It’s a temporary escape from the nightmares. In her dreams, she sees Crystal sitting on her old bed, puffing a cigarette, pleading with Janice for justice to be served.

Every other week, Janice speaks with Monroe County Sheriff’s Office Detective Sgt. Brad Swain on the phone. She knows the number by heart.

But with almost every call, it’s the same. No updates, he’d say, but maybe soon.

One afternoon, Janice was running errands when she heard a rumor from a city employee — there had been an arrest in Crystal’s case.

How could nobody have informed the family? She called Swain as soon as she could. The phone seemed to ring for hours. Nonetheless, it was a false alarm. Go figure, she thought.

Janice keeps a makeshift memorial in her kitchen that was once a china cabinet. It reminds her to keep pushing. Crystal’s ceramic frog collection is perched atop the cabinet. The frogs will be given to the girls, but they are still so young.

In the middle of the cabinet, there is a small wooden box.

Janice carefully fishes out the contents as she begins to weep. Three yellow kernels, plucked from a stalk in the cornfield where the remains were found. A crow’s feather also from the cornfield. A dried flower from Crystal’s burial service. A toy tractor, symbolic of the farmer who found her oldest daughter’s body that October morning.

Janice wrestles with the thought of Crystal’s unfinished life. The quality time they never spent together. The conversations they never had about the girls, about the meth. She was away with her boyfriend, Henley, most of the time. Long before she was killed, Crystal had been a ghost.

***

In their trailer on the west side of Bloomington, Tony raises his girls alone.

Sometimes he imagines how their lives might have turned out if Crystal never left that afternoon three Septembers ago.

Tony wants to believe that Crystal would have finally found a job and made something of herself. She’d be three-years sober and would spend time with their daughters. She’d do their hair and sing to them at night. When they were older, she’d take them shopping for their first bras.

“Who knows,” he says, “she might’ve even got back together with me.”

He used to have a photo of Crystal on the living room wall but took it down because it unnerved Abby.

“Mommy’s looking at me,” she told her dad.

Abby would talk about seeing her mother in the house, still alive, standing in her room. The visions made Tony nervous, but he tried not to dwell on it.

From the beginning, Abby asked questions about her mother and her death. Once, she asked her father why the casket hadn’t been open at the funeral.

“After you’re dead for a while,” he told her, “you kind of turn dark like a banana.”

As Abby grows older, her curiosity intensifies. Abby has already put it together that her mother did not die of a heart attack. She knows she was murdered. The 9-year-old’s questions keep coming.

“What do you think happened?”

As time goes on, Tony knows that Abby will ask more questions about what her mother was like when she was alive. She’ll want to know how her parents met, the things they did together.

When that day comes, Tony says he won’t talk about the drugs or about how she kept leaving and coming back. Instead, he’ll show his daughters pictures from family parties and the vacation he and their mom took in Tennessee, when Crystal was still a regular part of their lives.

He’ll tell the girls about their mother’s sense of humor and how she used to sing with them and play Candy Land and Ring around the Rosie.

Tony wants his daughters to remember their mother like the smiling woman in Abby’s journal, standing with her arms open wide. As far as he’s concerned, all of the bad things about Crystal disappeared with her.