In an ironic twist, the IU project studying the spread of misinformation across social media has fallen victim to this phenomenon itself.

The Truthy Project is run by the IU Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research via the School of Informatics and Computing.

The name is a reference to Stephen Colbert’s concept of “truthiness,” when something feels true but isn’t necessarily so.

Since 2011, the project has received almost $1 million from the National Science Foundation.

The goal of Truthy is to study how memes spread through social media.

Papers on Truthy’s findings have been published in about 30 peer-reviewed journals.

Products of the ongoing research are already available.

In short, it’s just like any other federally funded study.

Unless you are Federal Communications Commissioner Ajit Pai, who claimed “the government wants to study ‘social pollution’ on Twitter” in an opinion column published Oct. 17 in the Washington Post. He insisted the government’s interest in such a study is Orwellian, an attempt to silence opposition on social media.

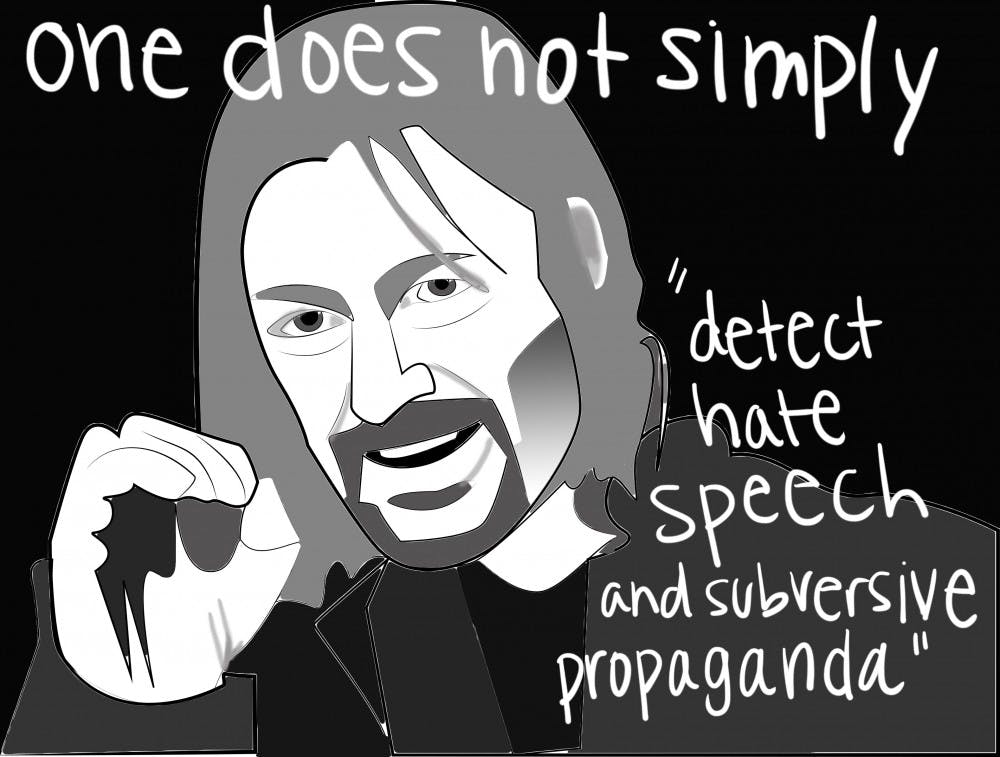

These claims arise in part from the researchers’ suggestion that their results might “mitigate the diffusion of false and misleading ideas, detect hate speech and subversive propaganda and assist in the preservation of open debate.”

Truthy’s results could be used that way — by average Twitter users, who now have access to tools that could help them sift through the clutter.

The government isn’t studying anything, let alone making any policies against so-called Twitter propaganda.

And yet, a congressional investigation is under way.

Political conservatives have been especially wary of the project.

Rep. Lamar Smith, R-Texas, chair of the United States House committee on Science, Space and Technology, called it a “misuse of public funds” that supports “limiting free speech” in a prepared statement.

Fox News’ Megyn Kelly wondered on air, “How is (Truthy) going to be used against the average Joe?”

In short, Megyn, it’s not.

If anything, the Average Joe will be more able to discern fact from fiction thanks to the work of IU researchers.

If Joe happens to be a student, he could gain valuable insight into human interaction with technology by working on the project or reading its results.

Many of us already read similar studies for class — on the partisan attitudes of likely voters across the United States, on the effect of new technologies on traditions and social systems and on political speech and participation. Truthy’s products will likely be assigned soon, if they haven’t been already.

It seems as though conservatives aren’t attacking this study because it’s actually dangerous but rather because it’s politically advantageous.

So while the government does have an archive of our tweets dating back to 2006 and has admitted to spying on our phone calls and emails, we’re busy trying to shut down a project hoping to promote productive political discourse.

And we wonder why Congress can’t get anything done.