This week, the deputy director of the British Museum issued a memorandum of understanding to the Dja Dja Wurrung people, an Aboriginal tribe from Victoria, Australia, according to the Guardian.

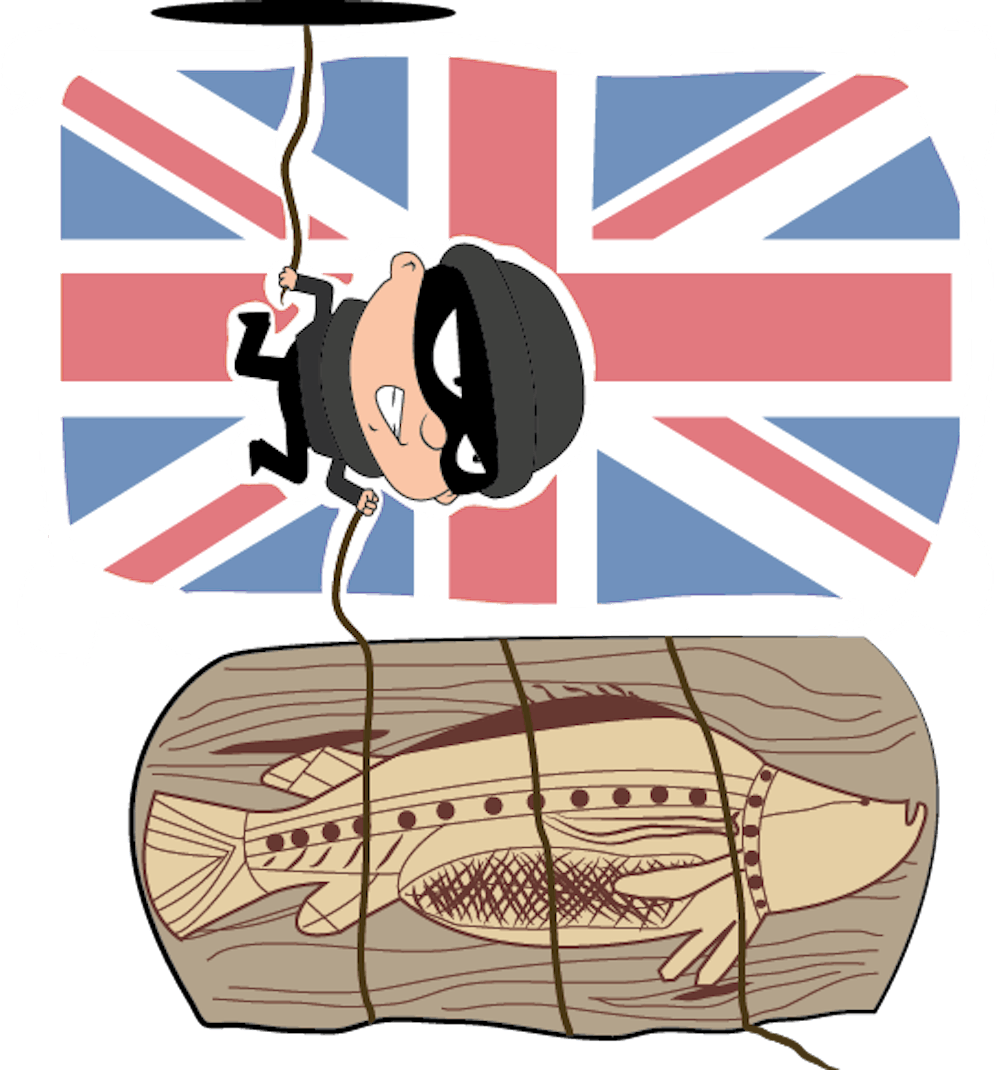

The memorandum concerns “shared interest relating to the objects associated with the Dja Dja Wurrung people in the British Museum,” referring to three bark artifacts sacred to the Dja Dja Wurrung that were stolen from them in 1950, reported the Guardian.

This memorandum is being seen by the museum and Aboriginal activist communities as a step toward the eventual return of these artifacts.

The Editorial Board believes it is absolutely necessary to settle disputes over ownership by returning items to their country of origin.

The items need not be given back in all cases nor without fair negotiation and trade.

This opinion excludes cases in which many countries claim ownership over a certain item, or if there is no dispute or claim from the originating country.

These factors complicate the matter and change a nation’s ethical responsibility.

The British Museum has very publicly come under fire for this in the past.

But museums all over the world house items and artifacts that don’t belong to the country in which the museum is located.

In instances like the case between the British Museum and the Dja Dja Wurrung from Australia however, the ethics are clear. Australia, first and foremost, is entitled to these artifacts.

The British Museum’s decision to work toward the restoration of these artifacts should take into account all of the ethical responsibilities of this practice.

And we should remember the historical significance ethical implications of the events such artifacts tell us about.

The museum’s website states, “The Trustees’ primary legal duty is to safeguard the museum’s collection for the benefit of present and future generations.”

However, the British Museum could make returns similarly to how other museums have returned artifacts.

In November 2006, the National History Museum in London, returned the remains of 18 Aboriginal people to the Australian government.

On some level, these things are part of human history.

Items and artifacts can be relevant to and appreciated by the entire world.

But Western nations cannot use this notion of a belonging to general humanity in order to justify keeping items from their rightful owners.

Appreciation of historical knowledge is quite different from appropriation of it.

Things would be different if this situation were the other way around.

Imagine a clan or tribe in an Eastern country possessed an artifact of great religious significance to a Western country.

Any Western country, such as Italy, England or the United States, would be held under the misconception the artifacts are safer in the host country’s hands.

For these reasons, we believe Western nations should consider negotiations to return these items.

We suspect neither England, nor Italy and especially not the U.S., would even consider the word “negotiation,” or stand for a “loan” period.

Western nations have perpetuated a paternalistic philosophy through colonization.

They would not necessarily be interested in completely respecting the rights of Aboriginal people.

These nations would simply demand the items returned.

Britain, in its colonialist days, had invaded 90 percent of the world’s countries using its massive military force.

Almost all of the items and artifacts in the British Museum were stolen in the days when Britain was a global empire.

But those days are gone.

It is past time those things be returned.

The restoration of a nation’s culture and heritage is a responsibility of humanity.

Such a solution should be embraced by all of us.