Shortly after President-elect Donald Trump gave his victory speech around 3:30 a.m., Kirkwood Avenue was silent.

There was no music from any bars and no crowd celebrating $2 Tuesday.

A car rolled down Indiana Avenue, and the driver leaned out the window to shout at a few stragglers on the sidewalk.

“It’s the end of the world as we know it,” he sang. “It’s the end of the world as we know it, and I don’t feel fine.”

Many Hoosiers were asleep at this time. Some went to bed knowing who had won, and some woke up the next morning to discover who the next president would be.

Students, faculty and staff would spend the next 24 hours trying to understand the effect this decision would have on the country.

***

Tables were pushed aside in Elizabeth Dunn’s 9:30 a.m. I304: Refugees and Displaced People class. For the first time this semester, the class of about 30 sat in a circle. Forgetting lesson plans, students faced one another somberly addressing the decision that was made clear only hours before.

“What will this mean for refugees?” Dunn asked her class. “What will this mean for the families we are working to bring to Bloomington?”

With a Donald Trump presidency, an executive order could potentially halt refugee acceptance in the United States, reversing a recent decision by the state department to allow about 60 refugees to relocate to Bloomington in March.

This could place the class’ semester-long project on hold indefinitely.

“This election leaves us in a really uncertain state,” Dunn said. “We’re extremely disappointed at the misinformation circulating about refugees during the campaign and extremely worried about the future of those who are being targeted in addition to already having lost everything.”

***

The Circle Café was warm and smelled of toasted bagels around 11 a.m. On the wall, Tim Kaine’s face flashed across the television screen, the election poll numbers scrolling beneath him.

“It hasn’t hit me yet,” a barista said as he snapped the lid onto a white mocha. “I feel like I’m going to wake up.”

His coworker shook her head. Suddenly, the screen switched. And there she was walking on stage, her purple suit lapel shimmering.

After one year, six months and 28 days since announcing her second run for President of the United States, Hillary Clinton was giving her concession speech.

Earbuds came out. Phones were placed down. Faces turned up to the screen. Nobody spoke. Only the fridge hummed quietly behind the counter.

Junior Chloe Rahimzadeh twisted around in her chair.

“This is painful and it will be for a long time,” Clinton said.

Rahimzadeh wore a black baseball cap low over her face, trying to shield tears welling in her eyes. She absently picked at the cardboard sleeve of her coffee cup.

She had gone home to Hamilton County to place her vote. Many of her friends hadn’t voted at all.

Rahimzadeh had watched the results come in until 11:30 p.m., when she couldn’t take it anymore and went to Kilroy’s Dunnkirk. She learned the final results later that night at a friend’s house.

She immediately started to cry and texted her parents. They didn’t want Donald Trump to be president as much as she hadn’t.

Above her, Clinton continued her message of gratitude, hope and unification.

“This loss hurts, but please never stop believing that fighting for what’s right is worth it,” Clinton said.

***

More than 50 people gathered around 12:30 in the Neal-Marshall Black Culture Center Grand Hall, as a spread of fried chicken, potato salad, cookies and more waited behind them.

“You can get two pieces of chicken,” Monica Johnson, director of the Neal-Marshall Black Culture Center, said to smiles and laughs. “Don’t get more than two pieces or I’m gonna clown you.”

More laughter.

Green had organized this event, called the “Relax Release Relate Luncheon,” first thing in the morning after seeing the results of the election. She wanted to provide a place for people to gather to vent, tune out or do anything in between.

Students, faculty and staff clustered at tables around the room. Niaima Geresu, an IU senior, sat surrounded by a handful of people speaking rapidly, often over one another.

“There’s a fan,” Geresu said. “And they strategically placed shit in front of it. And last night they turned the fan on.”

Some people sitting around her laughed. Others in the room stayed silent, zoned into their phones, headphones in their ears.

Geresu is an immigrant from Ethiopia, whose parents moved their family to the United States when she was only 1 year old. On Tuesday, Geresu cast her vote for Hillary Clinton, who she thought had a clear path to victory.

On Wednesday, she didn’t know exactly how she felt.

“My family didn’t come here for this,” she said.

As a predominantly black crowd lined up to fill their plates, hundreds of miles away, the first black president spoke of a peaceful transition of power.

***

David Ruigh began his Y335: Western European Politics class with a joke.

“We’re going to talk about the only topic that matters: IU basketball starts this weekend,” Ruigh said. “Just kidding. Let’s talk about the election.”

He opened the class’ 75-minute block to talk about the election results and immediately drew the connection to Brexit, the United Kingdom’s June vote to leave the European Union.

“We need to appreciate how extraordinary the result was,” Ruigh said. “In a lot of ways, Trump’s election illustrates a dramatic departure from politics as we know it.”

Students nodded in agreement as Ruigh noted Trump’s existence as an atypical Republican candidate. He challenged his students with questions.

“If he’s not a typical conservative, what is he?”

“How can you win an election if you go against the fundamental platforms of your party?”

“Regardless of who you were supporting, do you feel like your interests were represented?”

Many in the class shook their heads no.

***

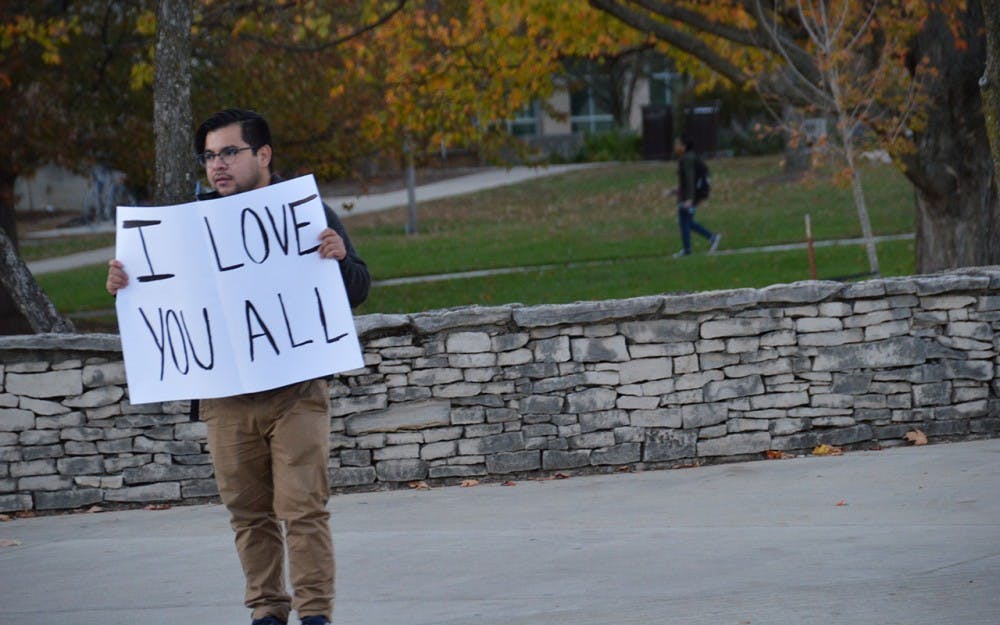

Jonathan De La Cruz, a first-year master’s student, stood on the corner of Jordan Avenue and Third Street around 6 p.m.. He had been there, next to the bus stop and across from Bear’s Place, for two hours. He never shouted or waved the sign he was holding in anyone’s face. He paced to stay warm and occasionally smiled when someone responded to him.

When De La Cruz found out about the outcome of the election, his heart sank, and he knew he had to do something. He was born in Texas but spent most of his life in Mexico. He said he couldn’t believe the country is in a state where people vote only out of impulse.

College students, men and women, drove by and honked. Mothers rolled down their window so their daughters could shout to him. Some thanked him, some cried. Some shouted negative thoughts, but De La Cruz didn’t care.

His message was simple, but he said recently it seemed it was becoming more and more difficult for people to understand. It was written in black Sharpie on a poster board De La Cruz bought after class.

“I LOVE YOU ALL”

This story was compiled by Laurel Demkovich, Nyssa Kruse, Carley Lanich and Liz Meuser.