During their rise in the 1920s, Nazis drew parallels between prostitutes and Jews, two groups they opposed, to convince Germans of a conspiracy against their country, IU professor Julia Roos said Wednesday afternoon at the Eskenazi Museum of Art.

The association was part of what Roos discussed as a volatile history of opinions around sex work.

“Prostitution is so emotionally, politically charged that people’s sensitivity varies,” Roos said.

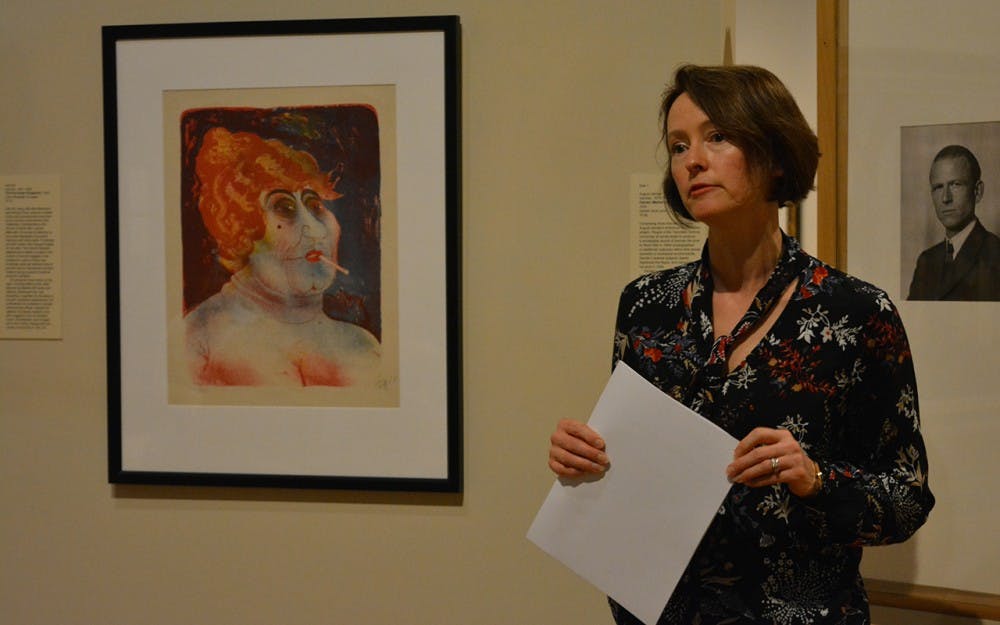

During her Noon Talk, one of an ongoing series of lectures at the museum, the associate professor of history stood next to a print called “Kupplerin,” or in English “The Procuress,” a piece by German artist Otto Dix, in the Gallery of the Art of the Western World on the first floor. The work tied Roos’ research to the museum.

“The Procuress” depicts a heavyset prostitute from the shoulders up. Her skin is blue-white against a dark background, and the color of her bright orange hair is also used in muted tones on her cheeks and around her eyes. She has a mole on her left cheek. A cigarette hangs down between her bright red lips.

Prostitution was decriminalized in Germany in 1927, Roos said. Police would usually ignore the problem before then, but this system often kept prostitutes from being able to use their legal rights.

Women tended to see sex work as a women’s rights issue that could help equalize men and women, she said.

“Even conservative, religious women are very upset by the sexual double standard,” Roos said, narrating the country’s history with sex work.

However, the Nazis began to turn the country’s feelings about sex work around, Roos said. They reached out to the conservatives who were against prostitution and made the party seem like Germany’s moral purifier. People began to hate prostitutes, and they were compared to sewage.

Although Nazis spoke strongly against prostitutes, they later went against their platform, Roos said. They added brothels to concentration camps and used prostitution in an attempt to limit homoerotic thoughts.

Art museum employee Janelle Beasley said she thought the topic of prostitution in Germany was perfect for International Women’s Day.

Even though she wants sex workers to have rights, she said many others are still generally against the idea of prostitution and often forget that it’s a way for others to earn a living.

“It is still work and completely valid of receiving the same rights that any worker would receive,” Beasley said.

Beasley works at the museum, where she frames art, like “The Procuress,” that was created on paper.

She said she goes to the Noon Talks as often as she can and especially tries to listen when the focal point is a piece she framed.

Lucinda Berry, 59, said she and her husband drove from Terre Haute, Indiana, after hearing about Roos’ talk on 103.7 WFIU FM.

She likes Dix’s work for its social commentary, even though the message isn’t always clear, she said.

“There’s sort of an ugliness to it that causes you to think,” Berry said. “Are you supposed to be sympathetic or judgmental?”

It was interesting for Berry to learn how the Nazis used morality to convince the Christian right. She said this perspective seems similar to American political conspiracy claims.

“It’s kind of sad that history repeats itself,” Berry said.