At a time of widespread uncertainty about the direction of South America, the disappearance and death of Argentinian activist Santiago Maldonado has rocked both Argentina and Latin America.

The case of Maldonado, who disappeared from a protest led by the indigenous Mapuche people Aug. 1, and whose body was found Oct. 17, is indicative of a troubling trend toward authoritarianism in Argentina. Such a controversy has deep roots.

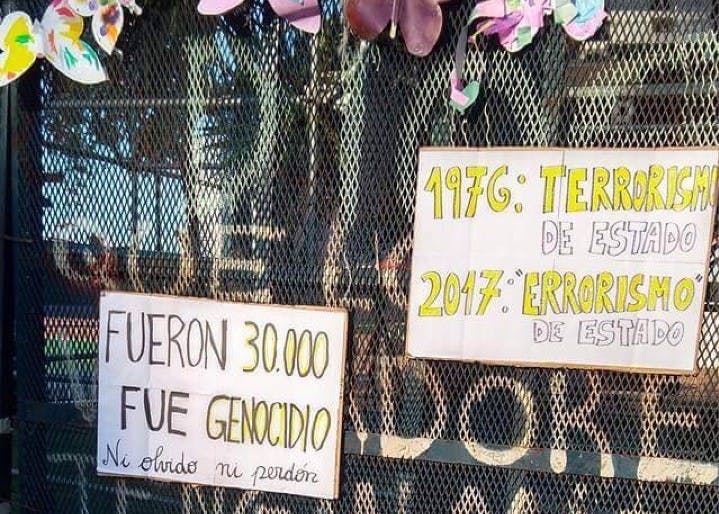

Invoking the 30,000 “forced disappearances” of the last U.S.-backed military dictatorship, Santiago’s disappearance highlights the growing use of political repression by President Mauricio Macri’s government. These recent efforts are largely meant to corral activists in a nation famous for its human rights and political activism.

Yet critically, the case of Santiago Maldonado should remind the world of the continuous, historic struggle of the Mapuche people, their fight against the Argentine state and a genocide of the nation’s indigenous peoples.

Despite his overt human rights violations, Macri remains one of the most popular leaders in Latin America with an approval rating near 47 percent.

Argentina is currently at inflection point in its history not known since its economic depression in 2001, when mass protests against an neo-liberal economic nightmare toppled five presidents in less than a month.

Since his ascension to office in late-2015, Macri has set out on a path to bring economically liberal values back to Argentina. However, the country rightly remains embittered by its parasitic relationship with international debtors and the disaster wrought by unrestrained, free-market capitalism in 2001.

One cannot downplay the effects of free-market reforms on Argentina during the 1990s. A report by the U.S. Congress from that time states reforms in Argentina were “faster and deeper than any country of the time outside the former communist bloc.”

By the late '90s, the effects of these reforms on GDP and poverty were stunning. Between 1998 and 2002, the economy contracted 28 percent, unemployment rose to 24 percent and the number of Argentinians living below the poverty line rose to 53 percent, including 70 percent of children.

Even in a nation that suffered on such a level less than 20 years ago, Macri’s government has sparked backlash not seen since 2001.

“What a time for you to be in Argentina,” I was repeatedly told during my travels through the country earlier this year, where I witnessed widespread protests against Macri’s reforms.

Macri continued his offensive against Argentina’s Left with his support for “dos por uno.” This law, ratified by two Macri-appointed Supreme Court judges, makes possible the release of hundreds of those convicted for human rights violations during the last military dictatorship.

Macri’s steadfast denial of the abuses of the military dictatorship are well known. He’s referred to the period between 1976 and 1982 as the “dirty war,” a propaganda phrase used by the dictatorship itself to justify its actions.

In a Buzzfeed interview, he even questioned the official number of “the disappeared” or los desaparecidos: “I have no idea. That’s a debate I’m not going to enter, whether they were 9,000 or 30,000.”

Macri’s own record on human rights is criticized the world over, most notably against indigenous activists. Milagro Sala, head of a well-known indigenous rights movement, has been jailed without charge since January 2016.

Like much of Latin America, Argentina finds itself in the dissipating shadow of the Pink Tide, an era that brought left-wing, populist governments across the continent during the 2000s.

President Nestor Kirchner, Argentina's iteration of the Pink Tide, ascended to the presidency on the politics of anti-neoliberalism, Latin American identity, human rights and promises of a “serious Argentina.”

The policies of Kirchner helped lead Argentina out of the era of economic collapse and dictatorship. His tenure brought 11 million Argentines out of poverty, kicked the International Monetary Fund out of the country and doled out legal punishment for the human rights violators of the dictatorship.

Kirchner, succeeded after his death by his wife Cristina, both remain tribunes of Argentine populism much like former President Juan Perón and his wife Eva Perón.

However, their policies toward resource extraction laid the groundwork for Macri’s embrace of global agricultural and resource businesses, which spurred the oppression of the indigenous peoples and social movements trying to protect their land.

In the Kirchnerist era between 2003 and 2015, the number of mining projects and amount of hectares growing transgenic soy both grew, imposing on Mapuche land.

As noted by Argentinian journalist Darío Aranda, Macri “continues this trend: the removal of mining retentions, the lowering of agricultural retentions and labor flexibility for oil workers. More extractivism, more advancement over rural territories, where indigenous peoples and campesinos live.”

This bundle of trends in Argentina, Macri’s free-market policies and the longstanding struggles of indigenous peoples all intersected with the disappearance and death of Santiago Maldonado earlier this year.

Last seen by Mapuche activists under the detention of the Gendarmerie in the province of Chubut, Maldonado had committed himself to the Mapuche cause. The Mapuche’s fight for self-determination and the resistance of colonizers dates to the arrival of the Spanish crown.

Upon the establishment of the Argentine and Chilean states, a series of genocidal wars were launched to seize control of Mapuche territory to consolidate the rule of Buenos Aires over its periphery.

This genocide, euphemistically known as the "Conquest of the Desert” in Argentina, contextualizes the struggle of the Mapuche in the larger history of Argentine economic models and state repression.

Just as state violence against activists in the 1970s cleared the way for the implementation of a neo-liberal economic model, the genocide against the Mapuche and other indigenous peoples allowed for the early Argentine state’s agricultural-export model.

Identical tactics of the last military dictatorship — disappearance, torture, concentration camps and kidnapping — were also used against the Mapuche in the 19th century.

Yet despite mass organization of the indigenous since the last dictatorship and national laws recognizing their purview of their territory, this reclamation of land through state repression continues.

As Aranda succinctly states, like “the Campaign of the Desert, that had as its economic end the inclusion of lands to the capitalist market, the Argentina of the 21st century repeats the history of advancement over indigenous peoples.”

No other business has entrenched itself in the land-battles with the Mapuche more than Benneton, the Italian textile manufacturer. The firm owns over 2 million acres of land throughout Argentina, with 850,000 centered in the provinces of Chubut and Río Negro, the heart of Patagonia and Mapuche territory.

Disputes over land between the Mapuche and Benneton have been ongoing. Yet recent legal battles have led the company to retaliate with a lobbying and media campaign.

One cannot help but suspect the group’s influence in increased repression against Mapuche communities and the “application of anti-terrorist laws” against activists Human Rights Watch called a violation of the “fundamental processional guaranties” of “due process.”

In fact, it was at a protest of Benneton where military police sequestered Santiago Maldonado and in the region of the companies holdings where his body was found.

As the visibility of Argentina’s indigenous struggles increases, so does its established elite demonization of these groups in the media. The portrayal of the Mapuche as violent and the emphasis on the threat of “Mapuche terrorism” mars a lot of the media campaign, led namely by the newspaper Clarín.

The outlet described Facundo Jones Huala, a Mapuche held without charge by Chile, as “the violent Mapuche that declared war on Argentina and Chile.” Other headlines warn of “violence, anarchy and external support” and accusations of arms dealing and comparisons to ISIS.

Even with the finding Santiago Maldonado’s body in a river two days before recent mid-term elections Oct. 22, Macri’s coalition won half the country’s provinces and 42 percent of the vote.

The first man to break the Peron-esque hold on Argentina’s politics, Macri has led a quiet revolution out of the era of the Pink Tide and economic populism.

It is a revolution from the top, bolstered by the old forces of reaction: financial capital, social order and the view of Argentina as a pocket of Western civilization on a continent of “savages.”

Speaking from his bunker on election night, Macri declared “this is an era of permanent reformism.”

Should Macri saddle the nation with more debt, continue to shred labor rights and blatantly ignore the human rights of activists and the indigenous, then one of the great countries of Latin America could soon return to its darker era, one of dictatorship and economic brutality against the poor.

luwrobin@indiana.edu

@lucas__robinson