Between film events, screenings and guest speakers, the Black Film Center/Archive on the ground floor of Wells provides diverse programming for the Bloomington film sphere.

“We’re here for the preservation, the conservation, of the creative filmworks from people of African descent around the world,” director Terri Francis said. “We’re here for things that are already known as culturally and historically significant, and also those that are not known to be culturally and historically significant.”

One of its first programs will be the free-to-attend film series “Race Swap," which will be co-sponsored by the Black Film Center/Archive, Center for Research on Race and Ethnicity in Society, Cinema and Media Studies and IU Cinema, starting with the 1970 film “Watermelon Man” on Jan. 12. The film starts when a white insurance salesman wakes up to realize he’s turned into a black man overnight.

The second film, “The Thing with Two Heads,” will be screened on Feb. 2. The story follows a cancer-ridden white man who transplants his head onto the body of a black man.

The 1972 movie was advertised with the tagline, “They transplanted a WHITE BIGOT’S HEAD onto a SOUL BROTHER’S BODY!”

The third film, “Change of Mind” from 1969, will be screened on Feb. 23. The movie tells the story of a white district attorney having his brain transplanted into the skull of a black man and his new challenges involving a racially charged murder case.

“All of this is all based on people really feeling like black bodies and white bodies are very different and yet not different,” Francis said. “They really feel like they have a black brain, and that’s not how anything works.”

During the third week of January, film curator Greg de Cuir Jr. will visit campus for a workshop and screening series during his week long residency at the Black Film Center/Archive. This series is sponsored by the Black Film Center/Archive, College Arts and Humanities Institute, Underground Film Series, Center for Documentary Research and Practice, Cinema and Media Studies and IU Cinema.

Cuir Jr. will hold a series on avant-garde film on Jan. 19 at IU Cinema.

Next is “Cheryl Dunye: Blurring Distinctions,” a program co-sponsored by Black Film Center/Archive, IU Cinema and Bloomington PRIDE. Dunye emerged in the 1990s as part of the New Queer Cinema movement, and was awarded an internationally-recognized Teddy Award in 1996 and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2016. She was part of the directing crew for Queen Sugar, a drama series featured on the Oprah Winfrey Network.

A program of shorts by Dunye, created between 1990 and 1994, will be presented on Jan. 21. The program will discuss the influence Dunye had on documentaries and film of the time.

“Using a mixture of narratives and documentary techniques, ‘Dunyementary’ challenges social and cultural norms through a sharply funny and reflexive lens,” according to the Indiana University Cinema spring program.

Two films directed by Dunye, “The Watermelon Woman” and “Black is Blue,” will be presented on Jan. 22.

“The Watermelon Woman” follows a black lesbian actress in the ‘30s as she tries to answer questions about herself and her future. “Black is Blue” is the story of an African-American transgender man who is forced to confront his pre-transition past. Dunye is scheduled to be make an appearance on campus on Jan. 23.

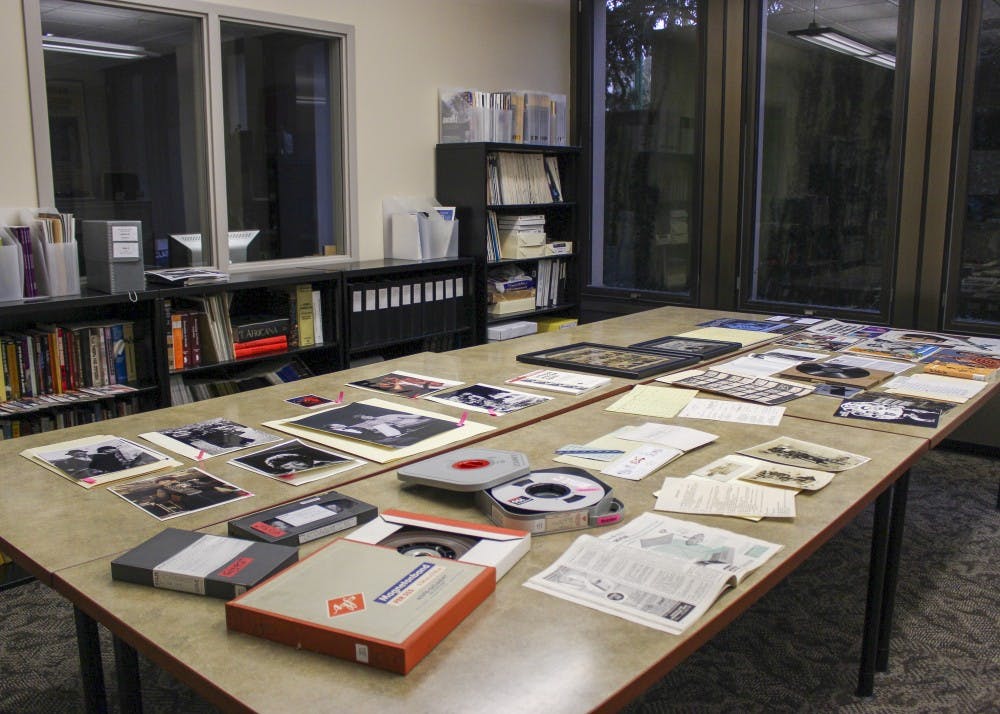

Between February and April, the Black Film Center/Archive will present the Black Film: Nontheatrical series, a monthly screening and lecture series revolving around films that were never aired on theater screens. The first archivist will be Candace Ming of the South Side Home Movie Project at the University of Chicago. The presentation will be on Feb. 8 at IU Library screening room in Wells Library.

Ina Archer from the Smithsonian African American Museum of History and Culture will visit in March.

A collection of film from African-American, LA-based Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company, housed at UCLA, will be presented by archivist Shani Miller in April.

“This African-American company based in LA took films of their picnics and their day-to-day work,” Francis said. “These are kind of corporate films. That preserves an incredibly rare history.”

By having these programs and keeping them safe and accessible, the central mission of preserving contemporary and historical African-American film promotes education, Francis said.

“You’re really looking at a kind of space that’s, on the one hand, an oasis, a kind of soft space, a quiet space for contemplating and studying this history,” Francis said. “It’s also very much a battleground space that’s also protecting these materials from being forgotten, and really laying the foundation for filmmakers to build on that heritage.”

After multiple fact and clarification errors, this story has been checked with sources for accuracy. IDS regrets these errors.