In a small lab at the Lilly Library, Jim Canary operates on an irreplaceable piece of United States history.

With a scalpel, he carefully scrapes off the leather lining underneath a fragment of a book’s spine. He must not let the tool break the intricate design on the other side.

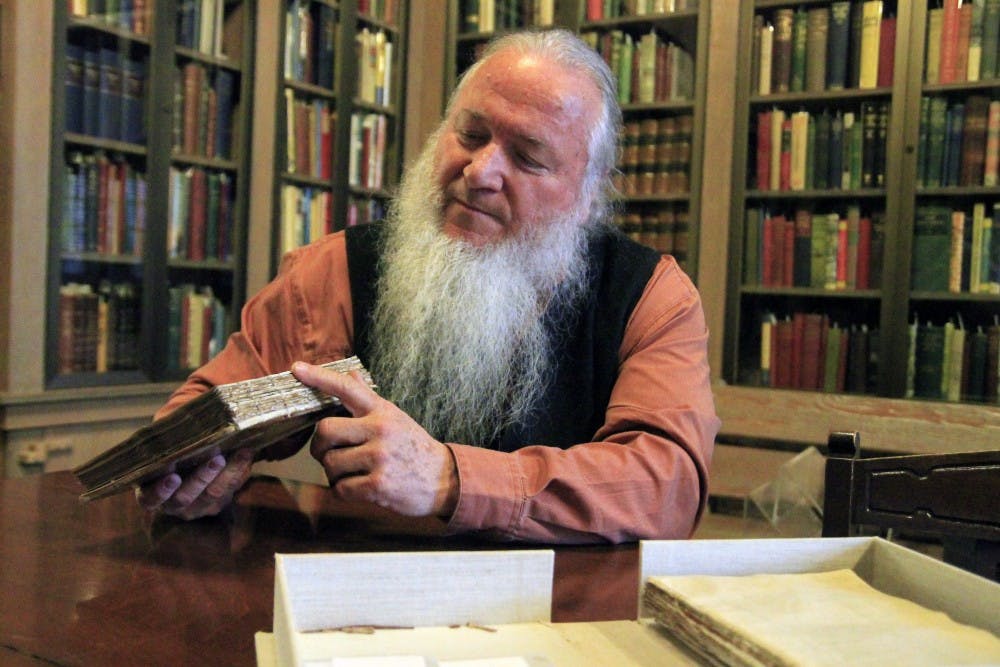

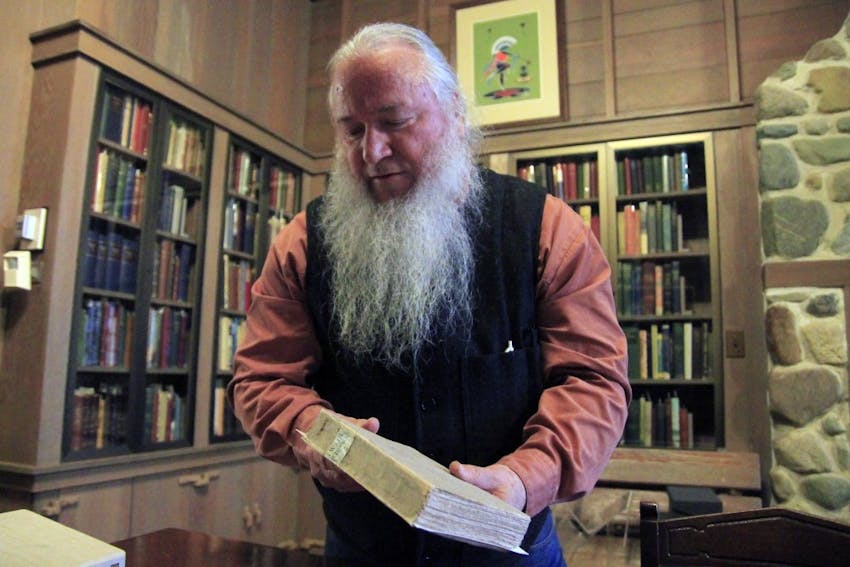

Canary, the Lilly’s head conservator, is repairing Thomas Jefferson’s personal copy of “Acts Passed at a Congress of the United States of America.”

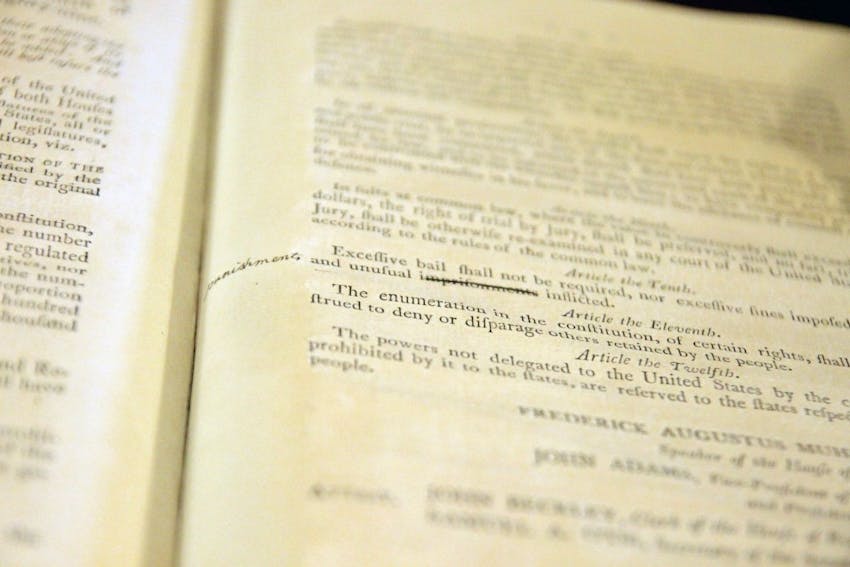

The book, one of only three known copies, contains the first published laws of the U.S., including the first printing of the Bill of Rights. The other two copies belonged to George Washington and John Jay. A red label on the front of the book reads “The Secretary of State” in gold letters. The book was presented to Jefferson from Washington.

The front cover of the book had become detached, so Canary has removed parts of the original binding from the rest of the book for his repairs. He will place a new piece of leather on the spine to stabilize the binding. The new leather will be dyed to blend in. He will attach the original fragments to the repaired spine.

As he works, he does not want any distractions. He won’t answer calls or listen to music. He prefers to keep his phone on silent. Like a surgeon, he needs to be completely focused.

He is operating on a book that describes the beginning of a nation.

* * *

Canary is a soft-spoken man with a long white beard and long braided ponytail. He has spent about half his life as the Lilly’s conservator. He is 64, and he has worked at the library for about 32 years.

The library opened in 1960 after the University received donations from philanthropist and book collector Josiah K. Lilly Jr., who gave IU more than 20,000 books and 18,000 manuscripts.

Now the library is home to about 450,000 rare books, 8.5 million manuscripts, 150,000 pieces of sheet music and 32,000 mechanical puzzles.

A Gutenberg Bible is on permanent display in the main gallery. Their 4,000-year-old Babylonian cuneiform tablets are the oldest objects in the Lilly. The collection includes a first printing of the Declaration of Independence. There are archives from writers like Sylvia Plath and Kurt Vonnegut. There are comic books, handwritten letters and a lock of Edgar Allan Poe’s hair.

These materials are slices of lives, Canary said. Inscriptions, marginalia and sketches provide insight into the people who owned and created them. Imperfections like torn-out pages and evidence of sloppy repairs tell stories about the objects’ histories.

Lilly director Joel Silver has worked with Canary for most of his career. He said the conservator brings passion and energy to his work.

“I don’t think there is anyone else who combines that enthusiasm with that specific level of experience with both Eastern and Western books,” Silver said. “He’s so deeply interested in all aspects of books, from early manuscripts through modern artist books. You can’t categorize him.”

The Lilly is open to everyone, and people can request to view materials in the Reading Room even if they not working on a specific research project. Yet the Lilly’s mission is also to make sure the collections are available hundreds of years into the future, Silver said. They have to balance the use of the materials with their preservation.

Canary’s conservation work is essential to the longevity of the collections.

The conservation department is small. There are only two full-time staff members working in conservation at the Lilly, including Canary and the exhibition assistant. Students also work part time in the conservation lab, working on projects like the construction of boxes or envelopes for the safe storage of materials.

Canary conducts repairs in the library’s conservation lab. The library also has access to the E. Lingle Craig Preservation Lab in the Ruth Lilly Auxiliary Library Facility, which is located on North Range Road near Fountain Park Apartments. Some of the Lilly’s materials are housed in the facility, and it has its own conservation staff.

Although preserving individual materials is a major part of his work, Canary’s main concern is the building as a whole. His responsibilities include protecting the whole collection by monitoring the environment in the library and preventing fluctuations.

Every morning, Canary receives a report on the temperature and humidity of the seven-story building. The ideal temperature is about 68 degrees. The humidity level should be about 47 percent.

The most valuable items in the Lilly are housed in vaults separate from the rest of the collection. They are monitored closely and have an extra layer of fire protection. Only a portion of the Lilly staff, including Canary, has access.

The lighting in the library is carefully controlled. Materials are covered in protective boxes and folders to prevent light damage. The light in exhibit cases is filtered, and the main gallery includes LEDs so that materials are not exposed to ultraviolet light.

If there’s a leak anywhere in the building, he has to address it immediately by moving collections to a safe place and arranging for repairs. Water could find its way through and under walls. It could reach the stacks and harm the materials.

Without a safe environment, whole collections would be at risk of collapse.

Another issue includes “slow fires” that devour pages from within their covers. Natural chemical processes can cause acidic paper to become brittle.

This means conserving modern materials can be more difficult than conserving old materials. Early printed books tend to be sturdier in both craftsmanship and paper quality, Canary said.

Following the growth of printing in the mid-19th century, books were generally created with acidic paper made from wood pulp instead of the linen and cotton rags that were used previously in most western paper production.

Objects like newspapers and early comic books are often printed on poor-quality paper. With such fragile pages, Canary might use sheets of a clear polyester film called Mylar to protect them.

“Some of the modern papers are so brittle, and they just crumble like dust,” he said.

* * *

Jack Kerouac changed Canary’s life.

He read “The Dharma Bums” as a high school student in South Bend, Indiana. The main character in the 1958 novel was inspired by the poet Gary Snyder, who was one of Kerouac's friends. The poet is known for practicing Zen Buddhism and living close to nature.

“I thought, that’s what I want to be when I grow up,” Canary said.

He learned to meditate. He became interested in practicing Buddhism, studying Asian languages and living in the woods.

Kerouac’s “On the Road” was also influential.

The novel, which was published in 1957, was based on the writer’s own life. It is about a group of friends who go on a cross-country road trip across America. It is one of the most famous works from the Beat Generation, a literary movement that included writers like Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs.

After graduating high school, Canary hitchhiked across the country. Like the main character in “On the Road,” he started his trip with $50 in his pocket. He continued these hitchhiking trips for multiple summers.

As he traveled, he collected books, including works by Beat and San Francisco writers. Canary also wrote his own poetry on these trips.

He met many people who knew Kerouac, including Snyder, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, David Amram and Neal Cassady’s family. He visited Ed White, an architect and close friend of Kerouac, and read letters the two friends had shared.

Canary said Kerouac’s writings about being on the road and being free appealed to him.

“I wasn’t so attracted by their radical lifestyle,” he said. “I was more attracted by his writing — his descriptions of people and places and just the immensity of the road and traveling.”

Canary started college at IU in the early 1970s. Although he started as a philosophy major, he later switched to an individualized major in Tibetan studies.

He took every class he could with the Dalai Lama’s older brother, Thubten Norbu, who was teaching at IU. He spent about seven years studying Tibetan language and culture with him.

As a student, he would skip classes to research at the Lilly Library.

When he walked through the doors of the library, he felt like its serene environment was separate from the outside world. He would often stay late to study materials related to the history of printing in Asia. As a student, he eventually got a part-time job in conservation at the Lilly.

During college, Canary lived in a cabin with his library of books, a collection of Asian artwork and notebooks of poetry he had written.

One day in 1978, a fire destroyed his home and his possessions. He lost his library, his art and his poems.

The fire showed him what it meant to lose almost everything.

* * *

A series of woodcuts at the Lilly portrays the end of the world.

The artwork depicts the Last Judgment of the New Testament. The black and white illustrations include images of angels, saints and a seven-headed dragon. Latin text from the Book of Revelation is printed on the back of the woodcuts. One print features a dramatic portrayal of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

The prints are part of Albrecht Dürer’s “Apocalypse,” which was published in Nuremberg in 1498. This work from the German Renaissance is one of the most valuable objects at the Lilly.

Canary’s job is to replace the binding of the woodcuts. The binding was too tight, causing the pages to break off after repeated handling.

To protect the book, Canary had to carefully take it apart. As he separated the pages, he used a magnifying headset to make sure he was not disturbing the paper fibers too much. He used a poultice to soften and swell the adhesive in order to remove the prints.

Now, Canary has to rebind the prints in a way that will not harm the woodcuts.

Conservation involves making a series of small decisions in an effort to preserve history. Canary tries to perform minimal interventions with the materials. He mainly wants to stabilize materials so they are safe enough to be used.

Exhibition assistant Jenny Mack has worked with Canary in conservation at the Lilly for about two years. Her job is to prepare materials for exhibition. She has worked for years at museums and libraries, but she had never worked in conservation to such a large extent before starting at the Lilly.

Canary is her mentor. He has taught her new techniques for conserving materials, including repairs and housing.

Canary has taught her how to create clamshell boxes, which are sturdy, custom-fit boxes for books that need additional support. She has learned to mend and flatten paper, needed when pages have been dogeared repeatedly and are at risk of tearing.

Sometimes the books and manuscripts become dirty, so she and Canary use “dry cleaning" erasers to remove dirt. They have to be careful not to erase intentional marks, like notes or signatures.

Conservation is a specialized field that involves chemistry and craftsmanship, Mack said. It is important to know the chemical compounds of materials, whether they are made of paper, leather or metal, to effectively repair them.

“In a hundred years, you don’t want something to deteriorate because of your attempt at repair,” she said.

Although his job is to make the Lilly materials last, Canary is aware the books and manuscripts are not going to be around forever.

His beliefs guide him as the library’s caretaker. Buddhism includes the idea of impermanence. Everything eventually comes apart and dissolves.

His beliefs help him to appreciate the fragility of objects, he said.

“In conservation, you’re looking for permanence, but you have to keep in mind always that these things are composite things, and they will eventually decay,” Canary said. “But what we try to do is slow them down, to make them available for as long as possible for people to appreciate.”

* * *

The fire gave Canary a different perspective on life and objects. It was a reminder of mortality.

“It gives you a sense of that’s how the world works,” Canary said. “Nothing’s here forever. You don’t get to hold on and keep anything at all.”

After the shock of losing most of his own poetry in the fire, Canary stopped writing.

When the cabin burned down, he set up a 22-foot diameter teepee next to the burnt spot where he lived for a few years. Most of his books got moldy from exposure to the elements. He lived there during the Blizzard of '78. When he wasn’t living in the teepee, he lived in a small cell-like space beneath the stairwell of his friends’ apartment.

Even as he studied languages at IU, Canary knew he wanted a career where he could use his hands as well as his head. At the Lilly, he found a profession that combines craftsmanship and history.

He also learned leather working, cabinet making and bookbinding. He interned at the Indianapolis Museum of Art for one day a week as he started work in conservation. For a while, he owned a bookbindery in downtown Bloomington.

In 2001, Canary became the caretaker of the “On the Road” scroll.

Indianapolis Colts owner Jim Irsay bought the original manuscript of Kerouac’s “On the Road” for $2.43 million in 2001 at an auction house called Christie's.

The manuscript is a fragile, yellowing scroll made of taped sheets of paper. It is nearly 120 feet of text that Kerouac typed within three weeks in 1951. He typed about 100 words a minute.

The end of the manuscript is missing. Kerouac wrote on the scroll that it was eaten by a dog — a cocker spaniel named Potchky, who belonged to his friend Lucien Carr.

One of Canary’s jobs as the "keeper of the scroll" is to take care of the manuscript as it travels. He carefully rolls and unrolls the scroll at the museums and libraries where it is displayed. He makes repairs when necessary.

Canary has read the whole scroll, and he was fascinated to see the differences between it and the final version of “On the Road.” He said he considers parts of the manuscript to be more intense and insightful than the published version. The scroll also includes the real names of Kerouac's friends, which were later changed.

He was concerned about something happening to the scroll, so he and Irsay decided to digitize the entire manuscript using high-resolution scans.

“I thought that anytime this plane could go down, and it could be lost forever,” Canary said.

* * *

One night last year, the words came back to Canary.

He was in Chicago for the installation of the “On the Road” scroll at the American Writers Museum. He was particularly inspired by its “Word Waterfall” light installation, which features a wall covered in seemingly jumbled words. Literary quotations are illuminated in the collection of words before dissolving into the background.

“I could just feel these words coursing through my veins,” he said.

That night in Chicago, the sounds of sirens and the screeching of the train woke him up in the middle of the night.

Words and images were running through his head. He envisioned the riders on the “L” train as skeletons. He thought about all the unknown lives behind the windows in the buildings of Chicago. He thought about how he used to write poems all those years ago, before the fire took them away.

He could not simply stay in bed and fall back asleep. He had to capture the words before they faded away.

Canary grabbed a pen and started writing a poem.

“I look up and the words are returning like so many migratory birds/I greet them with love and provide them material for nests and seeds for food/There is life and for this I am grateful.”

* * *

In the conservation lab, Canary continues his surgery on the spine of Jefferson’s “Acts Passed at a Congress of the United States of America.”

After a while, he’ll have to stop to take a breath. He’ll take a break from the intense operation and move on to something else.

It will take him months to completely finish his repairs of the book. He still has to rebind Dürer’s “Apocalypse.” Other conservation projects are next in line, including the deathbed editions of Walt Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass.”

But for now, he wants to be right there with Jefferson’s book. As he cautiously scrapes underneath the leather spine with his scalpel, he wants to feel any resistance.

His focus becomes increasingly narrow, until that small fragment of a book is the only thing on his mind.

This is his world right now.