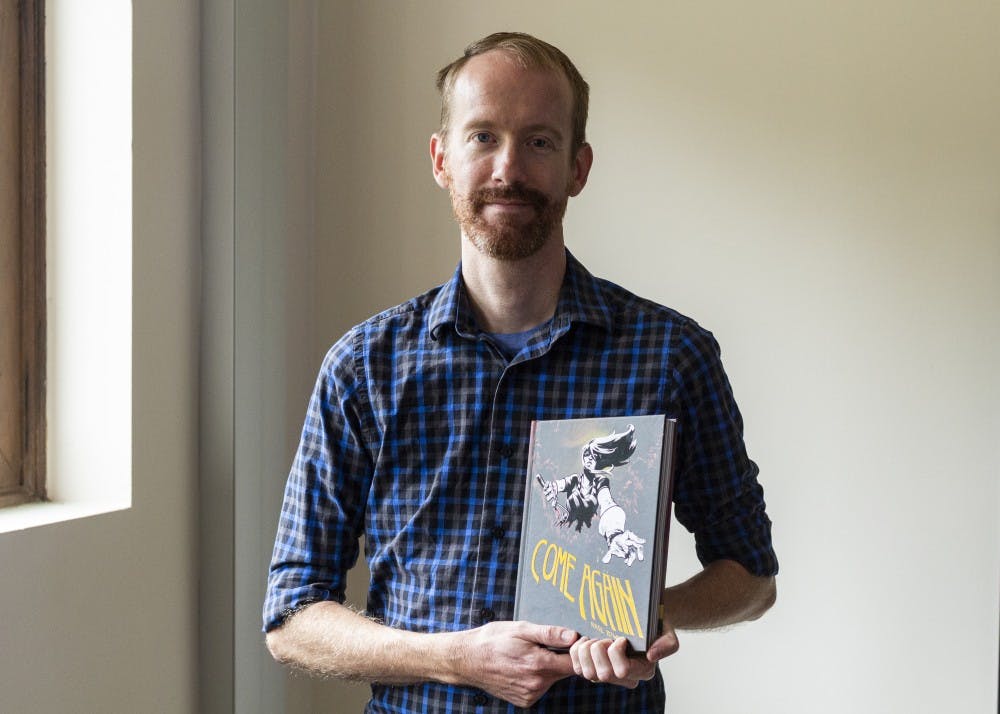

Graphic novelist, National Book Award winner and Bloomington resident Nate Powell sat down with the Indiana Daily Student to discuss his new novel, “Come Again.” Set in a 1970’s “intentional community” high up in the Ozarks, Haluska and her son, Jacob, have to battle with their own desires, secrets and love as a mysterious monster is out to destroy them.

Powell is co-author of the nonfiction “March” graphic novel series, which tells the story of Civil Rights activist John Lewis and won a National Book Award in 2016.

IDS: Tell me about the inspiration for “Come Again.”

Powell: It’s a book I actually started writing before the “March” trilogy. Back in 2010, 2011, I’ve been working on it and abandoned a sci-fi fantasy that involved the same protagonist, but as I became less interested in the story, certain themes started to emerge that I was more interested in. That’s around the same time, late 2011, I became a parent. There are these themes of secrecy, privacy, intimacy and tension between openness and privacy, and inherently unsupported structures, and also in the changing of ideals, reckoning with those, looking around and seeing that perhaps your ideals don’t line up with where your life is anymore. All these sort of more powerful voices for me as a I became a parent.

It’s a very interesting setting, one that I’ve never read out. Like you said, a hippie commune in the Ozarks. What was your process behind choosing that as a locale for this very remote story?

I’m from Arkansas. I’m from Little Rock. This is northwest Arkansas, but I’m familiar enough with the region and the ways in which remoteness allows for different communities of people to find their space, or to thrive. It has a really weird dynamic tension in the Ozarks, where you have fairly progressive, well-funded college towns, which are one county over from wretched, white supremacist havens, which are then one county over from hippie, crystal-selling tourist trap towns. It almost makes this Bermuda Triangle of weirdness and tension. Once I realized the story was going to be in the south, and I moved it back to my home state of Arkansas, the question was, “Where is the most like the alien landscape 10 years ago in the story? Oh, it’s obviously in the remote hills in the Ozarks.”

The color palette in this work, especially the reds and the blacks, do feel very remote, very Martian, but also sinister and dark. What went into approaching this palette and this artistic style?

This is my first full-length book that actually is colored. This reddish tone was what I knew I wanted to use for the book, but once I realized they were going to need to print it in full color no matter what, I thought, “Well, if I need to add any other colors here and there, I can.” All of a sudden, sort of like a visual coding system emerged, by which I could use color and negative space, or the absence of color, to denote shifts from past to present, from the overworld to within the reaches of the cave, memory to forgetting, internal-external landscapes. All these things sort of emerged, and if you’re using the power of the language of comics correctly, this is the kind of information you can hopefully communicate in a nonverbal way.

If there’s something you want readers to take away or experience in this graphic novel, what would that be?

One of them has much more to do with the existential relationship aspects, both within Haluska’s family unit, and in a romantic sense, in terms of the love and devotion she has with her friend group that she’s brought into adulthood. A lot of that is to look around and recognize when the shape of your life has already changed. Speaking for myself, there are times when I’ve discovered I’m kind of a ghost of my own life, and it’s kind of moved on without me, and I’m still living in a situation that doesn’t work for me, or I don’t realize that I’ve given up on the possibility of change for certain things in life, or doing what might be healthiest or best for me or my family or community, or whatever. Until you listen to that voice, you’re going to keep on being a ghost. It’s a poisonous thing, in the way that relates to the toxic nature of secrets, is that the more people try to justify and cover up the road that brought them to where they are, the deeper they dig themselves into something that’s fundamentally unsustainable. The other big takeaway, as far of the horror component of this book is concerned, I was really focused on illuminating the horror of a seeing so much casualness in the face an obvious crisis. We always have to have the voices ringing the alarms and shaking the scales from people’s eyes. It works in both apolitical and political ways. Ignoring the house being on fire is not going to keep the house from burning down.