A little girl, no more than 8 years old, sat across from me in a white plastic chair at a tanning salon downtown. Her baby fat-ridden body squirmed, and she played with her stringy blond hair nervously.

I was nervous, too.

Though I had 13 years of life experience on her, we had a strong nonverbal bond, as I waited on my roommate to emerge a bronzed goddess from one of the beds and she waited on an older sister or mother. Waiting was fine – what was nerve-wracking was being among the seven beautiful, twenty-something women waiting with us.

We both shot multiple glances at their perfectly toned and, well, tanned, bodies. Their manicured fingers and toes. Their Juicy sweatpants that fit just right.

The 8 year old and I, you see, were both pale. Not pasty, but we lacked that impeccable, perfectly pretty Cosmopolitan cover-worthy look the women around us absolutely achieved. We lacked perfectly straightened hair, firmed abs and pants that complemented the contours of our maybe not-so-supple thighs.

It took no words from the little girl’s pursed mouth to perceive her emotions. She felt ugly. She felt fat. She felt inferior.

I understood.

To be a beautiful young woman in a heterosexual mainstream American culture is to have power. It is to be admired and loved. At any typical bar on any typical night, it is the women – donning their lacy tanks and Silver jeans – being bought drinks (by the guys in the same shirt they wore to class that day). It is the women being gawked at. It is the women who are the gatekeepers of sex to the anxious, wide-eyed dudes.

“It’s a fucked up power,” says Jennifer Maher, who teaches a course called Gender, Sexuality, and Pop Culture for the Department of Gender Studies. Women absolutely attain power through appearing beautiful and meeting beauty standards set forth by and reinforced by advertisements, movies, television shows, and commercials for cameras, pudding, and air fresheners. This power is decided by, and therefore given by, men. They have to decide if a woman is worthy of it, Maher says.

“If you are cute, life is certainly easier. But A, it won’t last – no matter how much plastic surgery, eventually, we will all look old – and B, it is limited to how you are seen, not who you are,” Maher says.

Images of sexy women, which are ubiquitous in popular culture, shape people’s ideas about sexuality. What do we desire?

What the media teaches us to.

Women are the standard sex symbol in the U.S. media. Images of cleavage-exposing, lip-sticked, supple, creamy women’s bodies shimmy in music videos, dominate movie scenes and pervade magazine pages.

Women are not, as I’ve heard some of my peers say, “just naturally better looking than men.” There’s nothing biological about a woman’s body – her curves, her complexion, her hair, or her features – that are necessarily more attractive than a man. The notion that women’s bodies are more appealing is socially constructed. This means that consistent photographs, pictures, and images of sexy women’s bodies shape people’s idea about what is desirable.

Still, women who go to tanning salons, highlight their hair, and buy beautiful clothes to look like Maxim’s hotties or Laguna Beach babes aren’t wrong or shallow. After all, being pretty is fun, and taking pleasure in beauty is OK – I hate even going to Kroger without eyeliner.

This sexualization of the female body, Maher says, is not necessarily a “bad” thing. What is unfortunate, she says, is that a woman’s body is the prototype – as opposed to a man’s body – used to sell everything from soap to sports cars.

Maybe you’re familiar with the recent Nikon Coolpix camera commercial featuring a half-naked Kate Moss with bedroom eyes and a tight black mini dress. The commercial juxtaposes the camera’s sleek exterior with Kate’s equally... well... sleek exterior. This sort of advertising is what “the commodification of women’s bodies” means. The camera, like Kate’s body, is an object to be desired.

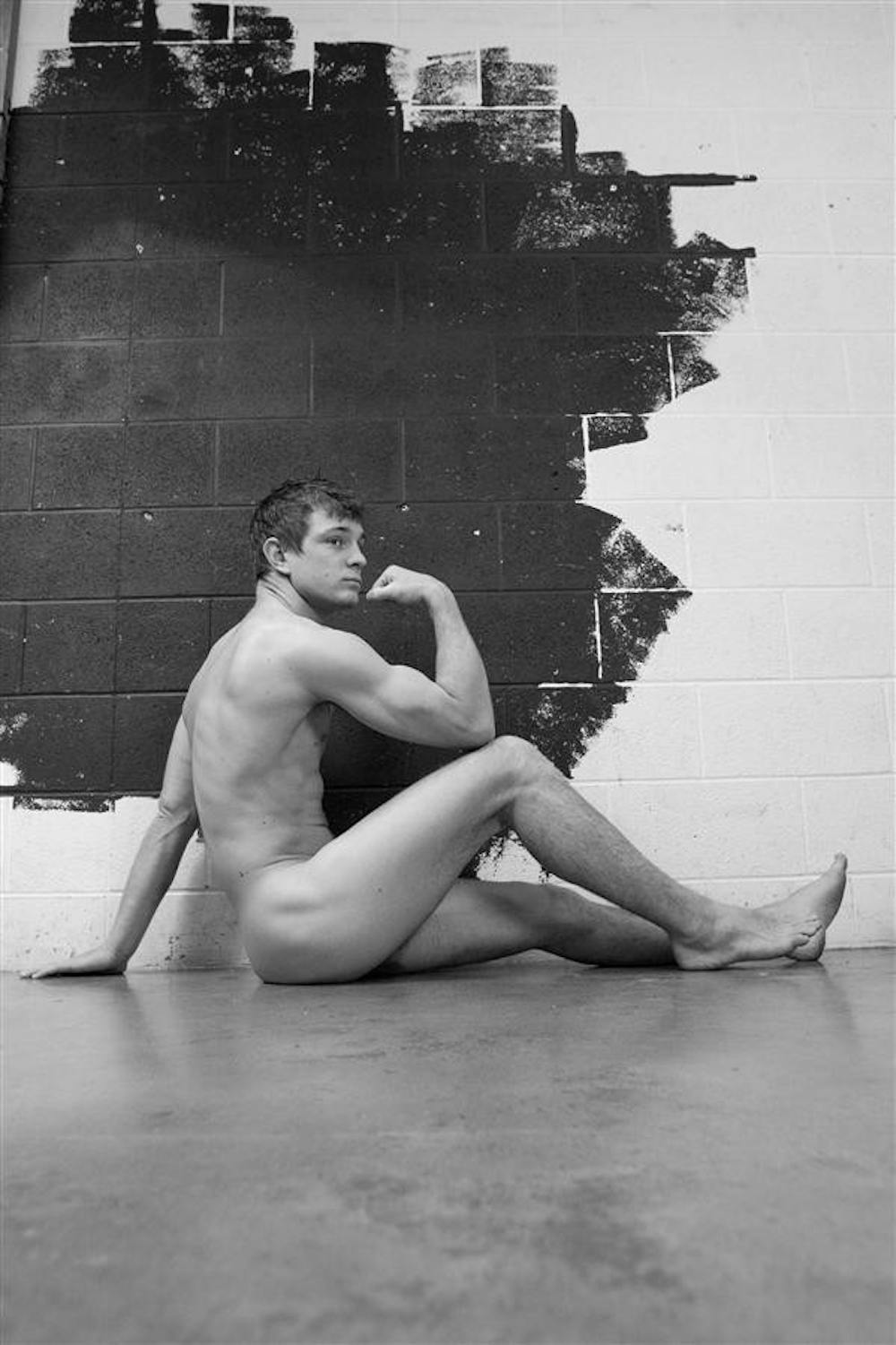

Can you imagine a more-than-half naked male’s body taking the place of Kate in the commercial? Would it work the same way if, instead of breasts, blond hair, and sinewy legs, the camera was associated with muscular thighs, six pack abs, and a sturdy jaw?

It would appeal to our sexuality in a different way, and, for the public, it would likely cause a stir.

While it’s true men’s bodies are becoming more objectified and lusted after in media, especially advertisements (Abercrombie and Fitch, anyone?), the dominant sexy body is that of a woman’s.

Heterosexual men easily take on their role as the viewer of sexy bodies because they get a lot of practice when images of women’s bodies are everywhere. How lucky for them.

The way that men see a woman – revealing soft, pink nipples on a Girls Gone Wild video, touching herself in Botticelli’s painting of Venus, or even just walking outside of Ballantine Hall – has always been a powerful force. How a woman should look has been constructed, throughout history, by men. And some women, in turn, work to conform to that projected image after all, it’s an easy access to free drinks, high self-esteem, and, most importantly, power.

Starting in the Renaissance era (we’re talking the 1300s here), wealthy men had pornographic paintings of female nudes in special “viewing rooms,” to which their male friends would occasionally be invited to indulge.

In the 1800s, fashion (like virtually everything else but babies) was designed and manufactured by men. Women wore billowy dresses designed to protect their perceived fragility. Later, they wore corsets to accentuate their often naturally ample curves.

In December 1953, Hugh Hefner began his regime over men’s magazines as the first Playboy landed on magazine racks (Marilyn Monroe, unsurprisingly, donned the cover). An abundant male readership got a glimpse of beautifully photographed, unclothed white women with bountiful breasts and skinny waists – images edited by men.

It was 11, and it was lunchtime in my sixth grade year. The boys circled around a copy of Britney Spears’ first album, the one on the cover of which is she posing with seductive innocence; a short blue skirt reveals her youthful – very sexy – legs. My fellow female peers watched and giggled at the boys’ expressed sexual interest, but I have to recall the deep dejection I felt knowing that I would never be sought-after like Britney.

Best-selling American writer Naomi Wolf understands my situation. She articulates in “The Beauty Myth” how, today, women’s sexuality works.

Little boys and little girls, she writes, both learn sexuality from a male perspective. After my prepubescent male peers expressed their desire for Britney’s body, I examined the CD cover more closely so that I could try to emulate her look (yeah, it never happened). I learned what was sexy for boys – but that was all.

Wolf concludes that the time girls spend learning the male perspective denies them the opportunity to discover their own desires.

“What little girls learn is not the desire for the other (sex), but the desire to be desired,” she writes.

“National Lampoon’s Van Wilder,” “The 40-Year-Old Virgin” and “Wedding Crashers” drew huge audiences of both men and women. All these movies feature male protagonists seeking sex from women. Extremely sexy female bodies are the norm. If you saw any single one of the noticeable actresses in these movies, she would be the most beautiful person you’d ever seen in real life. The real threat here is the normalization of this glamorous pretty that few women can imitate but all men learn to desire.

The scene in “Wedding Crashers” where women wearing (and not wearing) lingerie flop on beds isn’t included for a heterosexual woman’s libido. But they take it along with the males in the audience because they, too, experience sex from a male perspective.

Maher explains that mainstream culture is inherently masculine: taking our fathers’ and husbands’ last names, insults like “douche bag” and “sissy,” the fact that we use the phrase “mankind.” “Girls early on learn to identify with both genders,” she says. “To like most pop movies, you sort of have to ‘become’ male to identify with the film’s point of view – which is masculine.”

Since I identify as heterosexual and have learned to see myself as a man does, is it surprising that the purplish brown scar on my left lower shin bugs the hell out of me? I dread knowing I will develop the tiny blue varicose veins on my upper thigh that my mom complains about every time she puts on shorts. I worry that moles, pimples, pores, and tan lines make me appalling.

In 2005, women accounted for 91 percent of all cosmetic surgeries in the U.S. Last January, the Aesthetic Surgery Journal reported a study that found women who had body surgery – primarily liposuction or breast augmentation – reported a more active and fulfilling sex life. Some women even claimed they reached orgasm easier.

These women weren’t satisfied in bed until they drastically altered their bodies and emptied a remarkable portion of their bank account (Did you know the average cost of a breast augmentation is $5,500?) to fit an idealized standard of beauty.

Women who undergo plastic surgery didn’t construct the image of what they should look like on their own.

When women’s bodies are idealized and normalized as being without pubic hair, cellulite, boogers, and sweat, the perceived value of every woman’s body and her sense of self-worth and sexual value diminishes. More frighteningly, male desire for her may diminish, as well.

Wolf calls it “the deadening of the male libido to real women.”

Growing up, women are virtually on their own when it comes to learning to desire men. Women aren’t exposed to the panning of a camera on a man’s meaty calves, firm hands, viril biceps and forearms, a technique moviemakers use often to visualize a woman’s body. It even feels weird for me to have to describe a man’s sensuous features. I can’t articulate the solid sexiness of a man’s body like I can the curvy wonders of a woman’s. Can you?

I remember when I first saw “The Sandlot” in fourth grade. I was turned on by Benny’s character, and it made me uncomfortable. It felt strange and, because of my Catholic background, even sinful to wonder what his body looked like under his T-shirt and what it would be like to touch him. On the other hand, it didn’t feel awkward or wrong to ponder Wendy’s bathing suit-clad body and pretty red lips.

That was nothing new for me. And I like dudes!

What we must do, then, as media consumers, is not banish our porn or throw away our mascara, as discarding these things altogether may not be helpful – or even possible. We can never expect to completely unlearn what is consistently imposed upon us by magazines and movies.

It is essential, however, that we realize artificial women and unattainable fantasies are potentially detrimental to our – both men’s and women’s – sex lives, self-esteem levels, and imaginations.

Maybe keep that in mind when browsing magazine racks or watching MTV. In turn, maybe you’ll feel enlightened. And wouldn’t that be sexy?

Body Language

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe