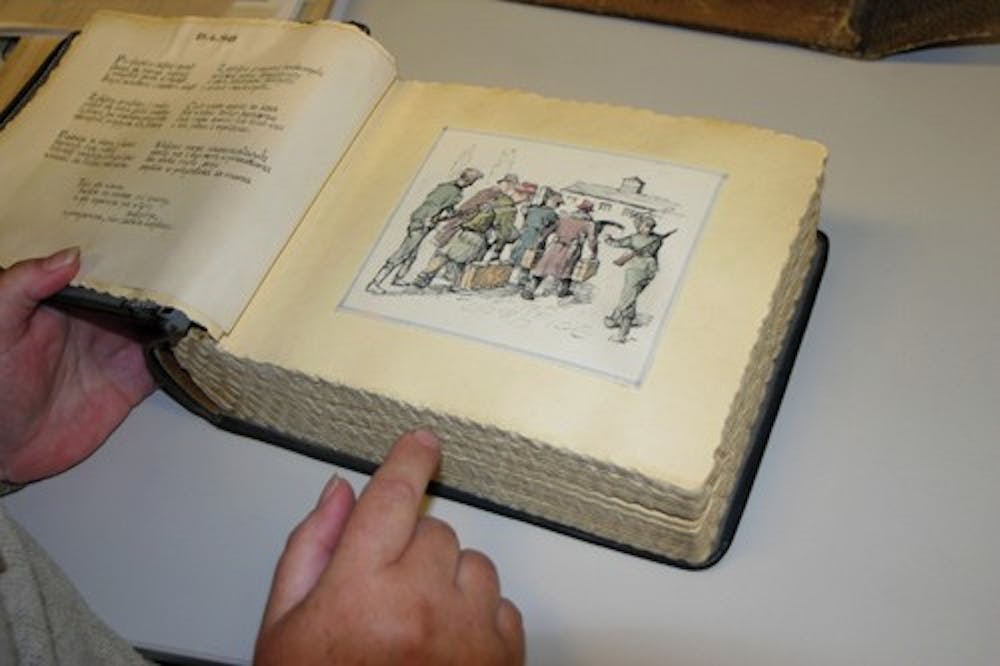

BAD AROLSEN, Germany Deep in Shari Klages’ memory is an image of herself as a girl in New Jersey, going into her parents’ bedroom, pulling a thick leather-bound album from the top shelf of a closet and sitting down on the bed to leaf through it.\nWhat she saw was page after page of ink-and-watercolor drawings that convey, with simple lines yet telling detail, the brutality of Dachau, the Nazi concentration camp where her father spent the last weeks of World War II.\nArrival, enslavement, torture and death – the 30 pictures expose the worsening nightmare through the artist’s eye for the essential and add graphic texture to the body of testimony by Holocaust survivors.\n“I have a sense of being quite horrified, of feeling my stomach in my throat,” Klages says. Just by looking at the book, she felt she was doing something wrong and was afraid of being caught.\nNow, she finally wants to make the album public. Scholars who have seen it call it historically unique and an artistic treasure.\nBut who drew the pictures? Only Klages’ father could know. It was he who brought the album back from Dachau when he immigrated to America on a ship with more than 60 Holocaust orphans – and he committed suicide in 1972 in his garage in Parsippany, N.J.\nThe sole clue was a signature at the bottom of several drawings: “Porulski.”\nWhat unfolds is a story of Holocaust survival compressed into two tragic lives – a tale with threads stretching from Warsaw to Auschwitz and Dachau, from Australia to suburban England, and finally to a bedroom in New Jersey where a fatherless girl makes a traumatic discovery.\nIt shows how today, as Holocaust survivors dwindle in number, their children and grandchildren struggle to comprehend the Nazi genocide that indelibly scarred their families, and in the process run into mysteries that may never be solved.\nThis is Shari Klages’ mystery: How did Arnold Unger, her Polish-Jewish father, a 15-year-old newcomer to Dachau, end up in possession of the artwork of a Polish Catholic more than twice his age who had been in the concentration camps through most of World War II?\nNone of the records Klages found confirm that the two men knew each other, though they lived in adjacent blocks in Dachau. All that is certain is that the dates of Unger’s internment at Dachau overlapped with Porulski’s during the three weeks the boy spent among nearly 30,000 inmates of Dachau’s main camp.\n“He never talked about his experiences in the war,” said Klages. “I don’t recall specifically ever being told about the album, or actually learning that I was the child of a Holocaust survivor. It was just something I always knew.”\nAs adults, she and her three siblings took turns keeping the album and Unger’s other wartime memorabilia.\nThe album also has 258 photographs. Some are copies of well-known, haunting images of piles of victims’ bodies taken by the U.S. army that liberated the camp. Others are photographs, apparently taken to serve as Nazi propaganda, portraying Dachau as an idyllic summer camp. Still others are personal snapshots of Unger with Polish refugees or with American soldiers who befriended him.\nBarbara Distel, the director of the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site, said Porulski probably drew the pictures shortly after the camp’s liberation in April of 1945. He used identical sheets of paper, ink and watercolors for all 30 pictures, she said, and he “would never have dared” to draw such horrors while he was still under Nazi gaze.\n“It’s amazing after so many years that these kinds of documents still turn up,” Distel told the AP. “It’s a unique artifact,” and clearly drawn by someone with an intimate knowledge of the camp’s reality, she said.\nHolocaust artwork has turned up before, but Distel and Holocaust scholar Michael Berenbaum, who is with the American Jewish University in Los Angeles, say they are unaware of any sequential narrative of camp life comparable to Porulski’s.\n“I’ve seen two or three or four, but never 30,” said Berenbaum.\nAssociated Press investigative researcher Randy Herschaft in New York contributed to this report. Arthur Max reported from Bad Arolsen, Germany, and Monika Scislowska from Warsaw.

Woman pursues Dachau album origin

Story of survival told with drawings, watercolors

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe