My tiny corner of the world is called Aix-en-Provence, France, a city of about 140,000. I live with a retired widow in a hotel particulier—private hotel—that has been in her family for nearly five generations. The ceilings of my room are about 20 feet high. I walk the halls, have tea in the salon and admire paintings on the walls, constantly imagining that this mansion is my own. I put on classical music and spin around, exclaiming how lucky I am to be in a mansion in the south of France.

But I am abruptly woken up from this dream when I hear a painful, pitiful gag outside my eight-foot-tall bedroom windows. It’s just after 4 a.m. and someone has vomited in the street, right outside my window.

The most posh discotheque—club—is about 100 meters from my house. The upside of having it so close is that I see a lot of beautiful people on their way there. The downside is that they aren’t as pretty on their way back—and neither are the contents of their stomachs.

But it got me thinking—maybe IU students aren’t so different from their Aixois counterparts after all. When I was at IU, I witnessed my fair share of drinks fighting back. Feeling at home, I plunged into Aix’s nightlife, not realizing that I would be abandoning my faux aristocratic life.

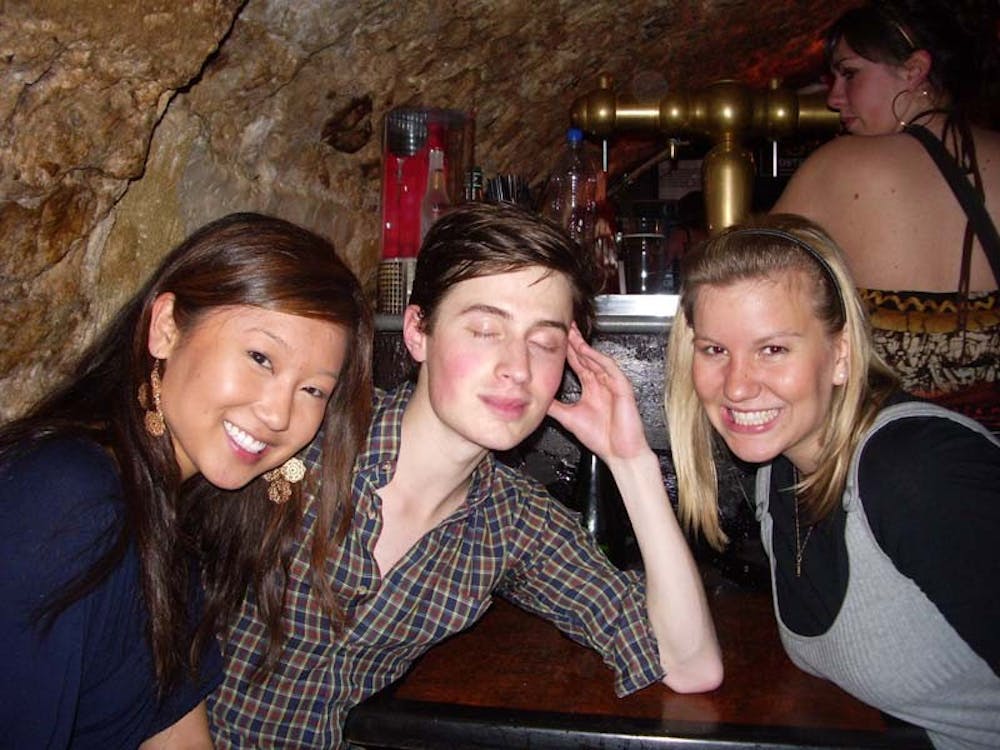

My favorite destination is Le Sunset, a dark bar that draws an unusual, freakish crowd and constantly smells like horrible body odor and stale alcohol. Its redeeming factor is a French twist on the iconic American ’80s night. At the beginning of the semester, my friends and I could be found drenched in sweat, dancing our brains out in the medieval cave known as the dance floor.

Approaching Le Sunset for the first time, all we saw was a black door—no noise or windows to offer a hint of a good time. We rang the doorbell and the door opened. Le Sunset is also remarkable because it features the fattest man in France as the bouncer. When 400 pounds of authority asked how many were in our group and demanded cover charge, I didn’t know whether I should run away or give him all of my money. Perhaps the combination of the confused, scared looks on our faces and our broken French signaled we weren’t from that area ... of the world. Imagine our excitement when we were waved in and told foreign students don’t have to pay cover. We were even more overjoyed when we saw the prices for some of the drinks. Wine was around 1.50 euros, and beers on tap were tasty and similarly priced.

So we danced away many Friday nights to second-rate ’80s songs until 3 or 4 in the morning. We worked up such a sweat some nights that steam came off our bodies when we hit the cold night air when we left. We went our separate ways to our French homes with French linens, thinking about the French toast we’d have the next morning.

But I would be restless. I had come to France to learn the language and experience the culture. Nightlife is an aspect of that culture, but when I woke up around 2 p.m. the following afternoon, I cursed at myself for having missed so many other cultural opportunities: daily markets, breakfast pastries and, if interested in alcohol, aperitifs (pre-meal drinks).

Halfway through the semester something changed inside of me. I set my alarm around 8:30 a.m., even on days I had no obligations. And then I would go: to the park, to the bus station, to a friend’s house or just exploring. You’re in France, I said to myself. See France. Be French.

Now, I only head to Le Sunset when I’ve eaten too many pastries and need to dance off a soft, crepe-filled tummy. Most nights, though, I am in my 17th-century bedroom, tucked in and exhausted from trying something different. Every weekend night, I still hear the cliques of French youth on their way to a crazy night reminding me of what I am missing. But the next morning, seeing either a small pile of throw up or a broken vodka bottle on the street, I am reminded why I am missing it. I’d rather read a book in a lavender field.

Something to write home about

A Hoosier in France

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe