Perhaps it’s still too early in the day to call a paintbrush and blank canvas Joel Washington’s transcending tools to eminence. It’s just past 10 a.m., and the Indiana Memorial Union custodian has three more hours pegged to a different trade’s tool. He wheels a squeaky gray trash bin through the corridors, atop sterile linoleum tiles in a routine repeated for more than 20 years.

But on this day, like many before, Washington is distracted. His eyes will sometimes wander. Other times they’ll resort to a daydream. Even as his movements become lethargic during one of these dreams – so slow he’ll bend to pluck a piece of trash – his neurons could not jump any faster. Co-workers wonder what Washington is thinking. “He’s different,” they say, and puzzle at what must amount to a spectacle of inspiration. Where to begin, what new project to start? The energy heaves and pulls as Washington’s trash bin wheels, ungreased and screeching quietly, never cease to lament.

Who knows what he’s thinking? Or how many times during the past two decades he’s slipped into the staff room during a shift – avoiding the watchful eye of friend and longtime boss Roy Robertson (“He doesn’t get special treatment,” Robertson says) – to sketch out the day’s idea. For years, he carried notebooks with him at work. Once, out of curiosity, he counted the sketches: more than 1,400 in all. “I still go back to them when I don’t have any other ideas,” he says.

Then again, perhaps he is like the rest of us, co-workers reassure themselves. Different but the same. Brilliant but – refreshingly – the janitor Joel they’ve always known. His art hangs locally in restaurants and behind bullet-proof glass in the IMU; his paintings are featured in the U.S. Embassy in Thailand and hang in galleries alongside the masterpieces of Indiana’s greatest artists. His work has swept local art competitions to the point, friends say, he seems embarrassed to enter. But to dominate the local market is just not enough. He’s backlogged on commissions and has been for some time. After his Union shift ends at 1 p.m. each day, he’ll return home, often to paint late into the night. Finishing one painting, he begins sketching the next.

To delve into Joel Washington’s world is to see each place in a psychedelic swirl of color. Those colors, often found nowhere in nature, find Washington in dreams. It’s a world shaped by a boyhood in Indianapolis, by jazz, skateboards, Sgt. Pepper, Andy Warhol, and later by the simple pleasures of antique tractor shows. For Washington, a black man, it’s a fight to live in a post-racial world, to be judged as equal among artists of all races, and to escape the novelty – the too-often-told narrative of a struggling, if emerging, painter who scrubs floors by day to help sustain a passion.

For those who have followed Washington for the better part of two decades, his work has matured and evolved, pushing to the edge the rules of color blends, hue, and intensity. He paints well, there’s no denying that. But to the extent any work is “good,” as valuable is the name scrawled in the bottom right. What does it mean to own a Joel Washington piece? Not much yet, the artist admits, but he insists he’s on the brink. More than likely, this confidence is similar to a faith in God: will and hope for it, convinced by the prospects of Heaven. But there is no denying a subconscious, stinging twinge. What if it never comes?

* * *

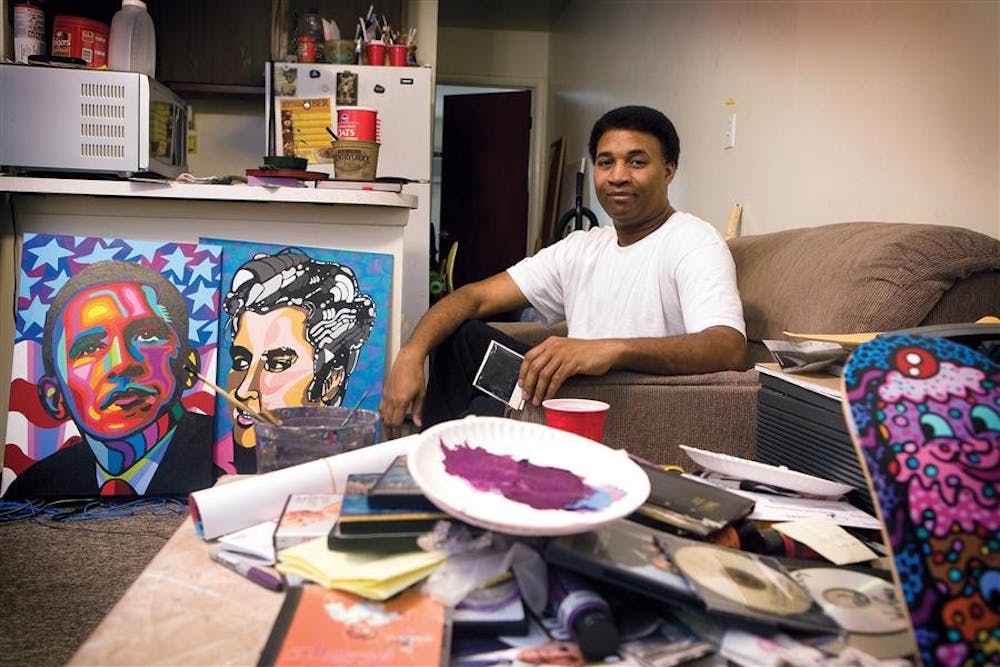

You can’t help to wonder whether Washington has always maintained the surreal, never-will-it-get-to-me attitude he displays in the Union, or during one afternoon in his apartment’s living room as he touches up a portrait he painted in 1987 of The King. In a white T-shirt and black pants, Washington swishes over the painting with relative ease.

It’s Elvis in his formative years – years before the plumper version took the stage. Down a short hallway, leading to his bedroom, paintings lean against the wall, one atop the other. More are stacked in the bedroom, paint supplies in the kitchen, a small aluminum Christmas tree next to the MTV-tuned television, and Washington, sitting forward on a cushioned chair, presides over the smiling King.

It’s cozy, he says, likening himself to a Beatnik, crammed in some small space in the East Village or San Francisco. He’s never read Kerouac, though, nor Ginsburg, nor any of the Beats; it’s more their legend he loves. More importantly, the space is inspirational. Not a single painting hangs on the walls. Their imperfections are too distracting, he says.

In 2001, a local newspaper – in an effort to frame him as a poor, struggling janitor, Washington says – described his furniture as shabby and “worn.”

Buying into the story, a concerned reader donated her coffee table. “I mean, it’s not that bad,” Washington says, later joking “that table will be up on eBay soon.” Growing up on the east side of Indianapolis, too young to understand the cultural rife around him, Washington missed the era’s artistic edginess and the emergence of pop art, his favorite genre.

The work of famed Andy Warhol notably inspired Washington. As Warhol’s art was meant to be shared – as dollar bills, Coke cans, and Campbell’s soup – Washington, from a blue-collar family, had greater access to the paintings. Today, he retains the art-to-be-shared attitude, but as he speaks about the genre, he seems to wonder whether he’s just too late. “Man, I just wish I could have been an adult during that time period,” he says, taking a moment to reflect. Forget the discrimination against blacks and the often-bloody battle for civil rights during that era. These were issues from which Washington’s mother – a strict, hardworking woman, as he describes her – shielded him.

Even so, in the subsequent years since leaving Indianapolis, he’s been shot with a pellet gun on Kirkwood Avenue, has been shrieked at in a McDonald’s in Martinsville, and has watched as a mother shielded her children from him as he trudged home from an eight-hour shift.

How to deal with his race is an issue Washington has considered for years; he’s wanted to paint these feelings, but only now does he say he’s artistically and emotionally ready. He lives in a world of colors, minus those on skin. He’s particularly wary to take special art grants for minorities, and those who work close to him say he hesitates to apply for those designed only for African-Americans (Washington, however, says at this point, he’ll take whatever he can get).

And coincidental as it might be, some of Washington’s biggest breaks have come from galleries’ desires to increase the diversity of their work. Ten years ago, in an effort to display greater variety, the Union asked Washington to paint the legendary black jazz guitarist Wes Montgomery, says Rand McKamey, the IMU’s preparator. By chance, Washington was already painting Montgomery. The product, an infusion of dreamy color blending with a deeply realistic rendering of the musician with guitar, hangs protected in the IMU as part of its permanent collection. Washington has no children. This, along with other paintings hanging in permanent galleries, is his legacy.

In similar fashion, Washington’s work was chosen for display at the Indiana State Museum. Then, while visiting recently, the U.S. Ambassador to Thailand – a Hoosier native – Eric G. John, visited the gallery and selected several of Washington’s pieces as part of an exhibit at the embassy. For the next few years, Washington’s works will hang alongside the sketches of Kurt Vonnegut and paintings by Robert Indiana among others.

He talks with amazement at the prospect of who might see his work. This could be the chance to break from the withstanding narrative that has long shaped people’s perceptions of him and his art. Joel Washington, the artist among dignitaries. But with the glimmer of success comes frustration. “I’ve made it internationally, but I haven’t made it nationally,” he says, only half-joking.

Mr. Washington’s paintbrush

Ten years since his first big break, local artist Joel Washington is on the brink of national acclaim.

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe