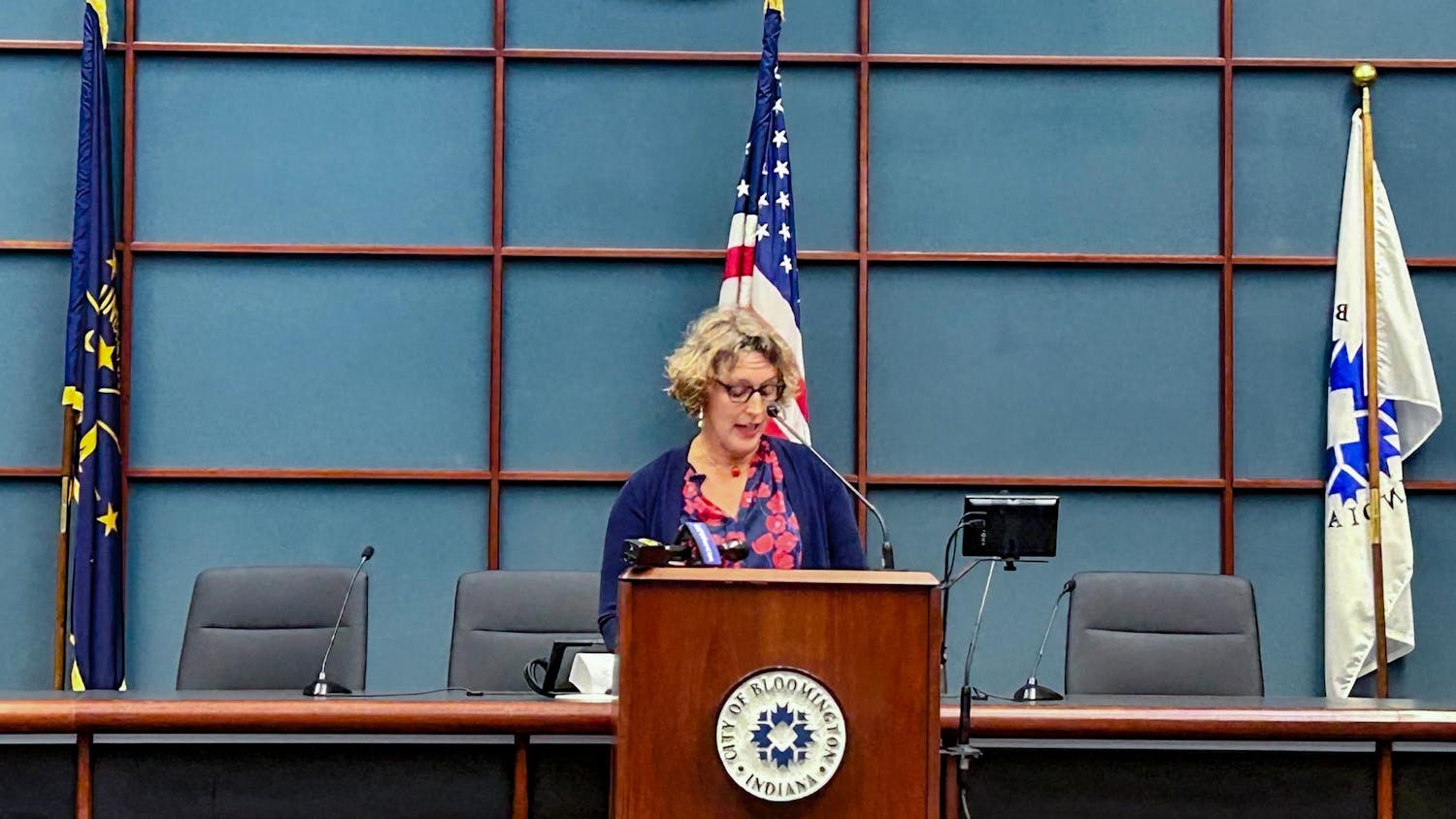

2010 is International Biodiversity Year for advocacy and education, but for IU professor Vicky Meretsky, every year is biodiversity year.

“We hope this will give us an opportunity to reach out, an opportunity for educating,” Meretsky said. “The people who work in conservation can only do so much without expanding the number of people involved.”

Meretsky is an associate professor in the School of Public and Environmental Affairs, but she is also an active member of the Bloomington community that supports biological diversity.

She is a part of the Indiana Biodiversity Initiative, the Sycamore Land Trust and the Nature Conservancy and is currently working on the Indiana Bat Recovery Plan. The bat is an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 and is likely to become extinct without intervention, she said.

“We have lost some species in Indiana,” Meretsky said, citing the now-extinct Indiana parakeet. “But we also have a few coming back and in safe numbers, like the white-tailed deer and river otters.”

Meretsky said she hopes the Indiana bat will soon be on this list and that she likes to think about biodiversity as the diversity of life on earth, a definition going beyond just the expansion of different

species to include genetic variety in many areas. But she said protecting biodiversity is really about protecting ecosystems.

“We know that healthy ecosystems make for healthy people,” Meretsky said. “Healthy ecosystems provide things like good water, good bugs to eat the bad bugs and wetlands that prevent flooding and improve water quality.”

The more scientific definition of an ecosystem, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, is the air, water, land and habitats that support all plant and animal life.

“The more and better ecosystems we get, the more we are protecting biodiversity,” Meretsky said.

Unfortunately, because of deforestation and unsustainable human activity, Meretsky said, many ecosystems are lost forever.

“Indiana’s biodiversity has declined greatly from what it once was,” said Tim Maloney of the Hoosier Environmental Council. “We’ve lost about 70 percent of our forestland, 85 percent of our wetlands and nearly all of our prairie habitats.”

Though Indiana can’t get back to the point it was once at, Maloney said, a great deal of work has been done to protect what is left.

“We should be doing everything we can to protect what we have left and make our current human activities more compatible with the environment.”

This involves using land more efficiently and incorporating the environment into building practices, Maloney said. A large part of this involves coordinating with private landowners who might not be in tune with the practices that support biodiversity, Meretsky said.

“The vast majority of land is privately owned, so it is impossible to think about protecting biodiversity without thinking about private landowners,” she said. “They may not think they make an impact, but it is so important that they are aware of how to help biodiversity on their land.”

Bloomington is a particularly biodiversity-conscious city, Meretsky said, but there are still many issues that need to be addressed.

“Because of the University and the kinds of people who are at the University, Bloomington is well-informed,” Meretsky said. “But we are not perfect. Bloomington is crawling with invasive species. For example, Dunn’s woods is dominated by an invasive vine that is terminating tons of native species.”

She said the domination of invasive species is one of the biggest threats to biodiversity. Such species can poison native animals and crowd out native plants. Once an invasive seed is planted, it takes 10 years for it to be completely gone, she said.

It’s all connected — anything that helps the environment ultimately helps biodiversity, she said.

“In a few years, there will be many choices that people can make in regards to the environment,” Meretsky said. “We want people to be looking at these possibilities. Let’s get them to hear about it now so that we can get them adopting these practices earlier and earlier.”

Bio-diverse?

Indiana has one of the worst biodiversity track records; but hope is not lost yet

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe