It’s nearly 3 p.m. The sunlight beams in through the quiet City Hall Atrium windows overhead, shining like hope on a rainy day, illuminating the smiles and frowns of children living with cancer.

The 4-by-6-foot, black-and-white portraits line the foyer of the atrium and the stairwell leading to the first floor.

Upon entering, in a photo to the left, Devin rests on her father’s shoulder. In another, Sean licks his lips as if it will be lunchtime soon.

These photos represent more than 200 children whose journeys are documented in Flashes of Hope, a non-profit, volunteer-run organization that strives to empower kids and their families affected by cancer through professional photography.

The photographers associated with Flashes of Hope are members of the American Society of Media Photographers, which sponsors exhibits of these photographs nationwide.

Each time a camera clicks, it is capturing the children’s personalities, their hearts. Each time a photographer captures a portrait of a child, it changes the way they view the world for the better.

TYLER

Ann Schertz, a Bloomington resident and member of ASMP, got involved with Flashes of Hope to contribute something to society, to give back. What she discovered was something so much more.

She sits at a yellow bench, the wind blowing her hair on a breezy spring day. She looks off into the distance when she speaks, her voice soft and low.

She, and other photographers who shoot for Flashes of Hope, have different experiences but they have the same goal for all the children they shoot: to make them stars for the day, as though they are magazine cover models.

Schertz goes for the Hollywood approach, an Austin Powers thing. The kids, who have been pampered with hair and makeup and are posed under natural, ambient lighting, love it.

“Lookin’ good, baby,” she is known to say on set to her subjects.

She shot Tyler, a James Dean-esque teenage football player, who wore his class ring around his neck. He hardly smiled, but he always engaged with the camera. That sort of engagement makes her job easier. And, Schertz says, he just knew he was cute, too.

Flash. She found out on the evening news he died last July. A bone marrow transplant could have saved him. As part of her job, Schertz can’t lose it. She looks off into the distance again.

“You don’t know how cancer feels,” she says. “One kid I shot found out she had cancer just three days before the shoot. I shot kids from their hospital beds when they were too sick to come out. They were always strong. I had to be strong.”

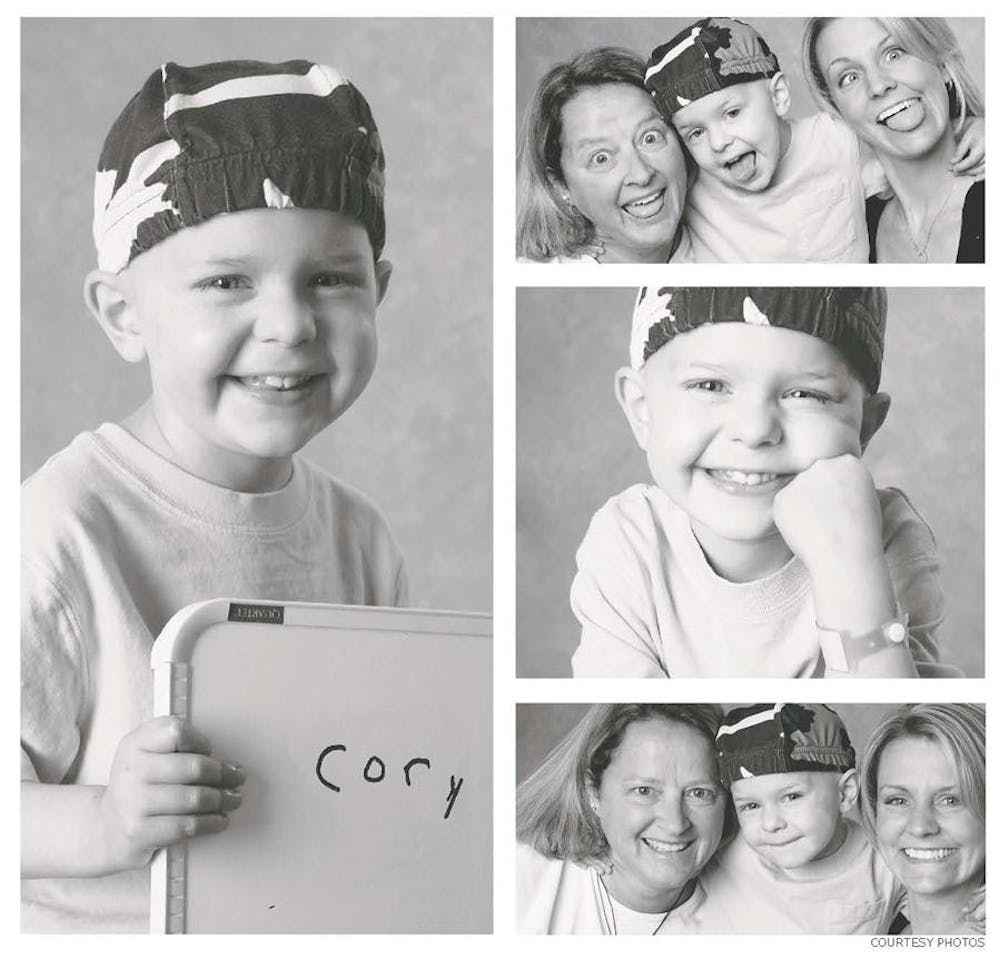

CORY

Cory’s smile is a testament to his strength. He exceeded the expectations of his doctors and lived until he was 5 years old. He was diagnosed with brain cancer at age 1 and given an average survival time of 11 months, with a 10 percent chance of living overall.

His mother, Kim Blue, remembers February 28, 2003. IV poles and monitor blips and the family’s tears were a norm of that day. That’s the day the nightmare began. But, Blue says, it was so much easier for the family to endure Cory’s fight because of his spirit — he loved to laugh and to make others laugh.

Cory also loved firefighters. They were heroes to him, because they fight fires.

Blue remembers a moment that occurred a few weeks before Cory died. She was holding him. He looked up into her eyes and swung his fist in the air.

“He goes, ‘Hey mom, I fight cancer,’” she says. “‘Firemen fight fires, I fight cancer.’ I told him, ‘You sure do, honey.’”

Blue is not sure if Cory ever knew what that moment meant to her. But, on July 27, 2007, she found out. It was 10:34 p.m.

Cory lay in his hospital bed, depleted of energy. He was unable to open his eyes. But, he seemed to be at peace.

Blue sat on the bed and held him. She leaned into him and said, “I love you.” To her surprise, he responded, “I love you too.” Cory died at 6:20 the following morning.

FLASH FORWARD

Flashes of Hope sent Blue six photos of Cory. One of them shows Cory smiling at the camera, his left fist resting on his cheek, exposing a hospital bracelet on his wrist. He is wearing a bandanna.

This was one of the pictures at Cory’s funeral, which Amy Robertson, the current Indianapolis chapter director of Flashes of Hope, attended. She is a friend of Blue’s and knew Cory well.

“Those pictures touched my heart,” Robertson says. “When you look at these photographs, you don’t see sick children, you see the spirit they have and the wonderful children they are.”

Those very pictures inspired her to participate in Flashes of Hope, she says.

Jim Barnett, another photographer for Flashes of Hope, knows his best work comes from emotion.

Barnett remembers photographing one girl at Peyton Manning Children’s Hospital. She had severe acne and her hair was messy. She had a palsy on one side of her face that prevented her from smiling straight. She was going to die soon of a terminal brain tumor. The photos had to be taken immediately.

Yet, she was gracious. She thanked him constantly.

Barnett positioned her under softbox lighting. Very simple, but elegant enough to capture what he was going for. A large group of people gathered behind him. Barnett decided then that this would be his best work because it just had to be.

The girl’s eyes twinkled, baring her teeth, showing her pride.

Flash.

Flashes of hope

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe