EDITOR'S NOTE

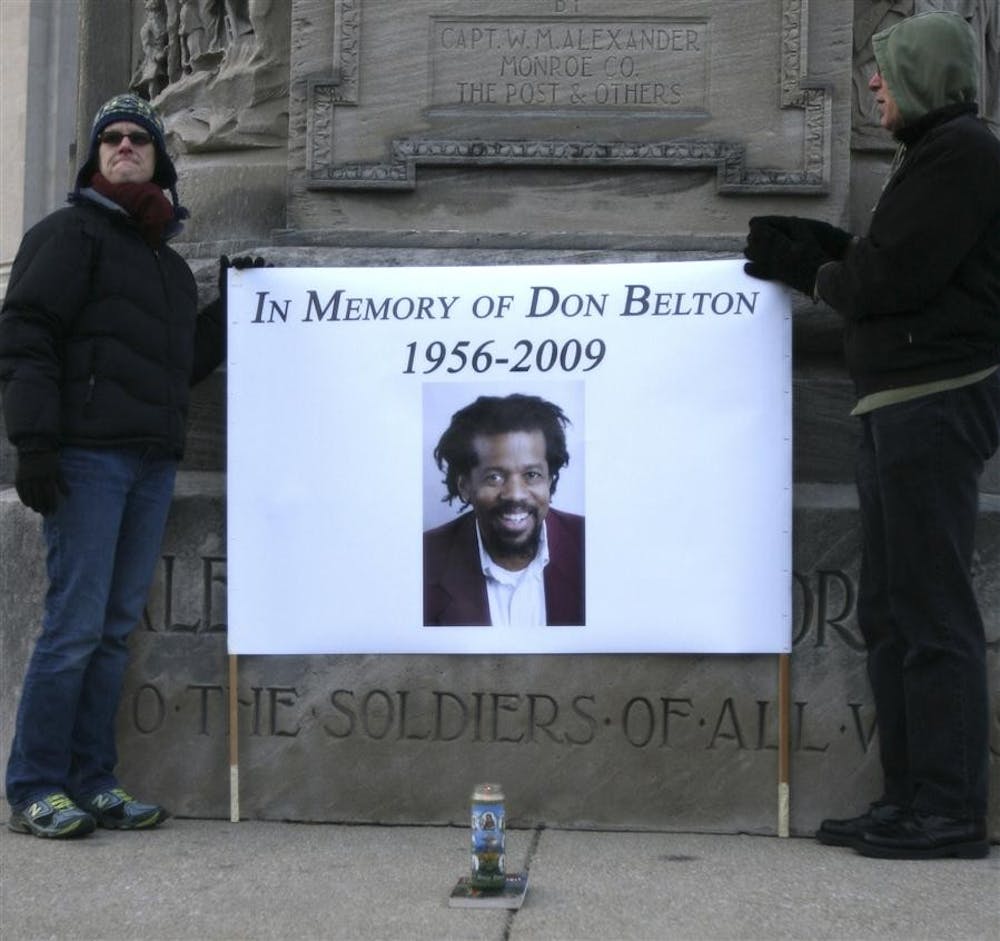

This article recounts the days leading up to and following the murder of IU English professor Don Belton. The information used to tell the story of the events that unfolded was obtained from court testimonies, police reports, interviews with police and interviews with family and friends of Belton’s. Michael Griffin was found guilty of murder April 14 and will be sentenced May 17. He faces up to 65 years in prison.

Don Belton did not respond to emails or phone calls. He was supposed to be in Honolulu with his friend, Mara Miller. Don bought a plane ticket to depart from Indianapolis International Airport at 8 a.m. Dec. 28, 2009.

But the morning after the New Year, Don was still not there.

In Honolulu, Miller poured her second cup of coffee; she waited and then picked up the phone.

She called local hospitals and local police. No Don Belton.

She called the airline.

“Was the ticket used?”

“No.”

“Was it a no-show or a cancellation?”

“A no-show.”

Then she called IU English Department Chairman John Elmer.

“... Can somebody stop by his home?” Mara asked.

Elmer’s words broke into her gently — Don has been murdered. Although Mara was just given the news, many other friends already heard, and it was not given to them in so well-versed a manner.

***

Debra Kang Dean, an IU colleague and friend of Belton’s, drove to his home Dec. 27 because he was not answering his phone. She needed his key so she could house-sit while Belton was in Hawaii. She knocked on his door and rang the doorbell — no answer. She dialed his number — no answer.

All she could see was a light on inside.

The next morning at about 10 a.m., she went to Belton’s house again. He was still not answering, so she peered through his front window. What she saw was a body — Belton’s — lying on the kitchen floor. She couldn’t tell he was dead until she opened his door.

She saw blood and what looked like flesh coming from his side and his head, which didn’t fall to any side, Dean said, but was facing straight to the floor.

She called 9-1-1.

“Oh my God ... He’s on the floor with blood all over ... 904, 904 Madison. It’s off Rogers.”

“Does he appear to be breathing?”

“I just got here ... there’s blood all over the floor... Off Dodds, Dodds.”

“I want you to calm down ... I’ve got it ma’am. I’ve got it.”

***

Don Belton, 53, came to Bloomington because he was searching for a place to belong. He wanted his English professorship to work. He wanted to publish a third novel. He wanted to settle. Scraping by from money he made writing two books, teaching, writing magazine articles and working at Macy’s outlet store was no way to live. It was hard for him to feel accepted anywhere as a gay black man.

In 2008, he left Philadelphia for Bloomington, unsure if any of this could be accomplished.

On Christmas day, 2009, Jessa Greiwe invited Belton to a party at her home on East State Road 45. Greiwe and her boyfriend, Michael Griffin, an ex-Marine, lived there.

Belton knew the couple from run-ins around town, and eventually, they had him over for dinner.

According to witness testimonies, Belton arrived in the afternoon. They drank rum sidecars and smoked marijuana. By evening, Griffin and Greiwe were heavily intoxicated. Belton, however, was not.

Griffin’s sister and her boyfriend were also there, but they left. Belton would spend the night.

According to Greiwe’s testimony, when she awoke in bed, Belton was giving Griffin oral sex. She then blacked out. When she awoke again, Belton was giving Griffin anal sex. Greiwe led Griffin into another room. Belton later followed them into the room and again had anal sex with Griffin.

Greiwe and Griffin both stated under oath that they were too intoxicated to remember clearly what happened, but Griffin said at no point does he remember resisting Belton.

The next morning, Belton snapped at Greiwe for asking him to leave. He demanded to speak with Griffin and asked for coffee.

***

Belton had always fought for a place he could feel accepted and welcomed. He found this comfort in many of his friends, but he needed a physical place as well, one that could accompany his personal and professional life. By late 2009, he found this comfort in Bloomington, despite a rough start.

Bloomington, 2008. The walk from Belton’s rented home to work and back was more than three miles. This was his first home at 922 W. Fifth St., the last house on the corner before White Oak Cemetery. The house overlooks hundreds of tombstones.

An eerie lonesomeness did not mix well with Belton’s stress from being a new English professor, and he developed stressed-related shingles. Belton sought counseling, but he felt the counselor was timid and “goofy” around black people, he told Gay Spencer, a friend from Philadelphia. He was far away from the roots he made in Philadelphia, the roots that took shape when he started eighth grade at William Penn Charter Quaker School.

The Philadelphia neighborhood in which Belton grew up, Strawberry Mansion, was a place of crime and frequent shootings. Two teachers pleaded the president of William Penn Charter Quaker School — the world’s oldest Quaker school — to interview with Belton. The president gave Belton a full scholarship.

A Philadelphia socialite, Ella Torrey, 86, met with all scholarship students at her alma mater, William Penn Charter. She enjoyed Belton, and he would eventually live on-and-off with her. He also became good friends with her daughter, Ella King Torrey, or Ella junior.

The life of a sexually confused black kid on the streets of 1960s Philly was lonesome. Belton would make detours to avoid a beating from neighborhood kids.

After high school, Belton followed Ella’s footsteps and graduated from Bennington College. The two remained close through their hardships — the suicide of Belton’s eldest brother, Morris; the deaths of Belton’s parents, Charles and Doris; the death of Torrey’s husband, Buzz and the suicide of Ella junior.

Don left behind many people when leaving Philadelphia, people whom he would frequently call. But he never spoke to his older brother Wayne Belton again.

Don and Wayne had their final conversation in Philadelphia, talking as the last two in a family of five. It was a bonding moment, the turning point Wayne was waiting for in their relationship — Don’s sexuality and Wayne’s Christianity were no longer the sole focus of the conversation.

Then Belton left Philadelphia. Again, he did not feel accepted by his family.

Wayne had no idea where Don went. He was just gone. It wasn’t unusual for Don to pick up and leave, Wayne said, but it hurt to think their last words were meaningless.

Torrey, Belton’s best friend, knew where he was, and so did Spencer.

Belton desired a full-time, secure job to lay new roots, Spencer said.

He talked regularly to Spencer while in Bloomington, but he no longer had the physical closeness of a neighbor-friend. He could no longer hear her move up and down the squeaky stairs outside his old apartment. The homes he now neighbored seemed void. Inside his home, the cemetery was all he saw.

Then Belton moved into a new home on 904 S. Madison St., and life improved.

He visited Friends of the Library, the book store tucked away in the corner of the Monroe County Public Library, multiple times per day, Faye Mark, who works at the book store, said.

Faye’s dark office, where she appraises books, is connected to the store. Just outside her office is a chair where Belton sat with the books he gathered — old literature, criticism, poetry — and chatted with Faye.

The day after the Christmas party, Dec. 26, Belton had plans to meet with local photographer Kip May at 2 p.m.

They met at May’s studio downtown so Belton could learn how to use his new camera. They opened the Nikon from the box, removed the cellophane and let the battery charge as they read through the manual.

They captured photos of each other for more than two hours.

Finally, at 4:40 p.m., Belton told May he had to leave for the library before it closed.

“Read your manual and shoot. We will get together again,” May said.

Belton rushed out the door.

When he made it to the library, it was his third time visiting that day.

Mark, Belton’s bookstore friend, was happy she got to say goodbye before his trip to Hawaii.

From 6 to 8 p.m. Belton walked into the place he ate most often, the Bloomingfoods near his home. He was wearing his usual tweed overcoat and still had the camera around his neck.

He would usually make a grand entrance to the store in a sort of delirium — “Where’s my girl? Where’s my girl?” — until Kathleen Craig, the customer service manager who considered Belton a best friend, was paged and notified that Don Cornelius Belton was in the building.

That night, Craig picked out Belton’s dinner — roasted salmon and greens.

Belton was giddy with excitement to leave for Hawaii. He was going to sit on the beach with his camera in one hand and some sort of alcoholic drink in the other,

Craig said.

On Sunday, he would do chores and pack.

***

On Dec. 27, Greiwe and Griffin ate breakfast with friends in Brown County and hiked along the Tecumseh Trail, according to Griffin’s testimony.

Griffin always carried knives with him, including a 10-inch peace-keeper knife he wore in Iraq.

The couple came home at about 2:30 p.m. and were going to drive into Bloomington to run errands. Greiwe, however, was tired and decided to stay home.

On his way into town, Griffin thought it would make sense to talk to Belton about what happened between them two nights before.

Griffin found a parking spot near Belton’s home. He still had his knife on him when he exited the truck. He walked toward Belton’s house, and it started to snow.

Belton was out by his car when Griffin approached, and they walked inside.

“If you’re busy, maybe I’ll come back,” Griffin said.

He was looking for an excuse to leave, according to his testimony.

Belton gave Griffin a glass of water and was on the phone with somebody discussing travel plans.

Griffin handed back the glass and asked him about what happened the other night.

“What do you mean?” Belton asked.

“I think you know what I mean,” Griffin said, adding, “What made you think that was OK?”

“You must’ve enjoyed it. You weren’t resisting,” Belton said, according to Griffin’s testimony.

Griffin then grabbed Belton. “No, you’re wrong,” he said.

Belton then pushed Griffin back with two hands. Griffin unsheathed his knife, holding it sideways in front of him. Belton lunged forward and grabbed the sharp end of the knife, cutting his hand.

They fell to the ground, fighting. Belton yelled as Griffin stabbed him 22 times until he stopped moving.

He stood up and looked at Belton and panicked. He wiped his knife on Belton’s pant leg and ran out the door to his truck. It was the first time he had killed somebody during his four years in the Marine Corps. As a squad leader in Iraq, he was proud to be able to come back home knowing he didn’t have to do anything bad.

The snow started to fall harder now. Griffin finished up his errands, returning movies to the Monroe County Public Library and filling up on filtered water from the Bloomingfoods near Belton’s home.

Griffin returned home and told Greiwe what he did.

“I’d rather die than go to jail,” Griffin said to Greiwe.

“Then you might as well kill me too,” Greiwe said, according to Griffin’s testimony.

Griffin told her she deserved to live and that he didn’t and that he just wanted to be with his son, Avery, and the life he was living didn’t feel like his own, according to Griffin’s testimony.

Greiwe left the next day for her parents’ house in Batesville, Ind. They drove her to the police station and told them her boyfriend killed Belton.

Meanwhile, that Monday night Griffin was at home with Avery, trying to put the toddler to bed. He wanted to stay up and kept kissing Griffin on the cheek.

“Why are you being so sweet?” Griffin asked his son.

Police lights flickered outside. Window glass shattered and the door was busted through. Griffin was surrounded by the Bloomington Critical Incident Response Team with guns and helmets and Kevlar. They tackled him to the floor and zip-tied his hands.

“Here I am. I’m the insurgent now,” Griffin thought.

***

Faye Mark hangs Belton’s photo and obituary in the bookstore on her wall of dead writers.

Ella Torrey answers a phone call from the Monroe County Coroner’s office, notifying her that Belton, the child she once took in, has been murdered. Moments after, she opens a Christmas card that just arrived. It’s from Belton and reads, “If the sun and moon should ever doubt, they’d immediately go out. — William Blake.

“I love you madly! — Don”

A counsellor at William Penn Charter said she wishes she would’ve spoke with Belton, her idol, when she had the chance and wipes her tears away with a pair of socks while the school’s alumni relations assistant is spooked from what she reads in Belton’s senior yearbook. In the book, there is no portrait or personal page like the other graduates, just a superlative:

“Don, Famous for optimism. Usually seen complaining. Ambition dying. Destiny living.”

A life lost: Belton’s final days recounted

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe