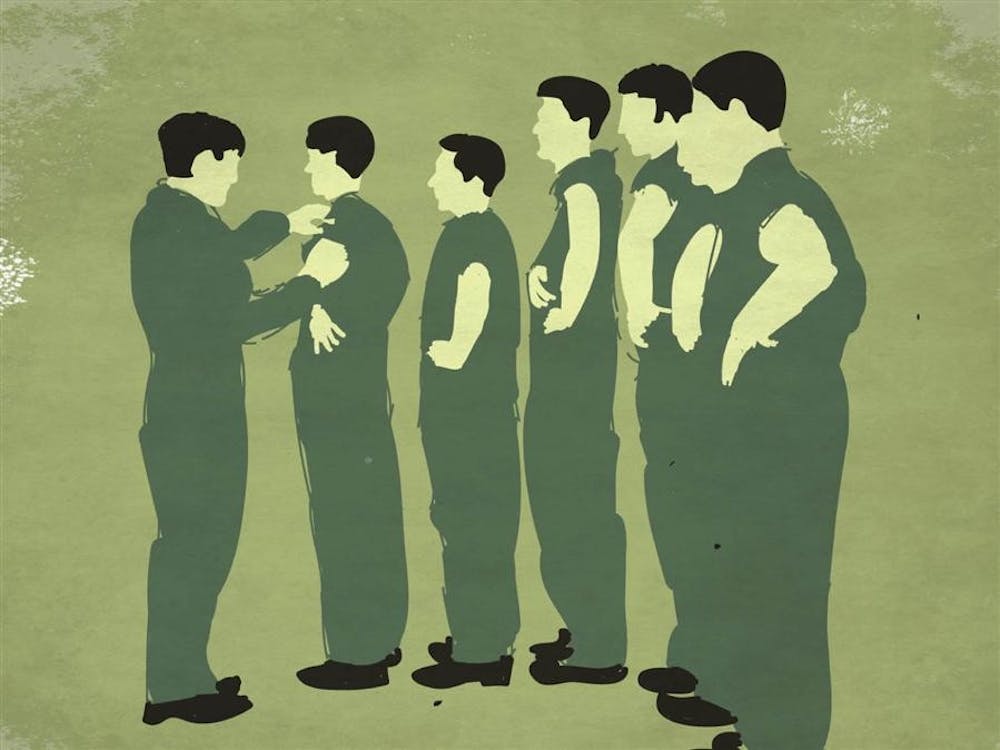

On a hot August day in 1968, Hal Kibbey fi led into a long room with

hundreds of other men, all of whom had received the same letter. The

mandatory physical would determine who could be drafted. The men were

clumped in groups of 10, driven like cattle in only their underwear,

clutching their forms as they moved from station to station. Kibbey

didn’t know it yet, but the men who were drafted would be headed into

Vietnam for the deadliest year of the war.

During the vision test, the other men snickered as Kibbey stepped closer

and closer to try to read the eye chart on the wall. His only chance at

deferment was that he was extremely nearsighted. He could fnally make

out the big E at the top when we was three feet from the chart.

“I was hoping my eyesight would save me,” he says. “It didn’t. They just verified that I couldn’t see.”

Hopefully it would be enough to keep him out of the infantry. Maybe they

would send him to an office somewhere to do paperwork. He could do

that. He had no qualms with serving his country. But he would prefer to

do it with a typewriter instead of a rifle.

The hot, heavy air carried the voices of the soldiers throughout the

room as they instructed the men and stamped their papers at each

station. The tension was palpable. Each man watched the man before him,

waiting to see what would happen to him next. There was no small talk.

Just a long line of anxious men called to serve their country– whether

they wanted to or not.

Kibbey reached the end of the narrow room and approached the last station.

“Did you bring any letters from a physician?” asked the soldier seated at the table.

“Yes,” Kibbey said. “I have this one.”

Kibbey had seen various doctors regarding “dizzy spells” he had been

experiencing for the past six years. The minute-long episodes weren’t

noticeable to others and didn’t affect his ability to walk, drive or

function in general. He never paid much attention to them.

His personal doctor wrote an official letter printed on hospital

letterhead. Any hopes Kibbey had for a medical deferment had vanished

when he read the single page. The letter included no recommendations, no

plea for deferral, just a list of the symptoms and a mention of

Kibbey’s “dizzy spells.”

“I remember being disappointed and thinking, ‘So what? That’s not going to do anything.’ But I brought it with me.”

That’s the letter he passed to the soldier waiting at the last table.

And for the first time, he was directed not further down that long, narrow room, but to the side. A deviation.

He entered a cubicle, where a physician’s eyes scanned the page in one flowing glance from top to bottom.

“He didn’t even read it,” Kibbey thought. “That was the last chance I had and he didn’t even read it.”

“I’m doomed.”

Without saying a word, the physician stamped the letter and passed it

back. After being turned door with a new form. The bustle and bright

lights were gone. Two new officials sat in relative darkness.

Kibbey handed the form to one of the officials, who read it once.

Without a word, he set it down and picked up another page. Kibbey only

heard one part: “You will be drafted only in the event of a national

emergency. Do not try to enlist.”

The wave of emotion overwhelmed Kibbey, but he couldn’t determine the cause of the saving news.

“Psychologically, I was a basket case,” Kibbey says. “I got down to what

appeared to be the bottom and was shotgunned back up to the top.”

He took the form, turned, and walked into the sunlight, trying to digest what had happened.

“I had my student deferment for life,” he says. “The letter that I thought was worthless was what saved me from all of it.”

Dodging the bullet

IU News Bureau reporter Hal Kibbey legally evaded the draft.

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe