Alone in his studio apartment, surrounded by Gatorade bottles and stacks of books, the runner sleeps. Peace comes easily when he's in a dream.

At 5 a.m., his alarm clock breaks the silence. He opens his eyes, and the turmoil begins.

Wes Trueblood’s mind lurches into the constant chatter he battles daily. Thoughts dart through his brain, swirling and swelling until they overwhelm. Before dawn, when he’s most vulnerable, the negative seeps in to conquer.

What if I don’t get into grad school? He worries.

If I don’t get into grad school, I’ll probably become homeless. If I become homeless, I’ll do drugs.

Thirty-year-old Trueblood knows what he needs to quiet the chatter. A run of at least six miles, two times a day.

He slips into his running shoes, then steps out into the 32-degree February morning. The sky above Bloomington is a deep shade of purple, lit softly by streetlights. He’s off, crossing the barren street in a steady jog. “Atlantis,” by Donovan, plays in his headphones. “Way down, below the ocean, where I wanna be …”

Trueblood winds through neighborhoods lined with darkened houses. He could run this route with his eyes closed. He created it — the six-mile out-and-back — three years ago when he got clean.

He runs downtown past the courthouse and the public library, dodging puddles that glisten from the streetlights. As usual, he passes the man who drops off newspapers on Kirkwood Avenue. He runs through the Sample Gates at the edge of campus and passes a group of the university’s groundskeepers on a smoke break. It’s the same group, every time.

“Hey,” Trueblood calls as he hurries by.

“Hey,” they reply, cigarettes in hand. “Good morning!”

Bryan Park marks the halfway point, and the runner stops to stretch. Ever since he stepped wrong off a curb a few days ago, the area above his left knee is tender. Trueblood runs 90 to 100 miles a week. A man of excess, he always wants more. If 20 miles feels good, why not try 21? If 30 feels great, what about 50?

Trueblood understands the consequences of overworking his body, and the only thing holding him back is the terrifying thought of an injury. Running keeps him on sturdier ground. Without it, he could slip back into his old ways.

By now, the sky has turned a lighter shade of purple. Cars speed by, the town wakes, and the noise in Trueblood’s mind grows softer. He feels light, calm.

Every day, Trueblood tries to outrun the demons inside him. He’s been running from them for three years now and doesn’t plan on quitting soon. He fears what would happen if he stopped.

• • •

His gig as a roofer pays the bills for now. But someday, Wes Trueblood wants to be a historian and teach young people the importance of the past. He’s quick to smile and speaks with confidence, expressing his thoughts with big words and quotes from Malcolm X and Nietzsche. His sister calls him her best friend. His mom calls him magnetic.

He’s loyal to what he loves, yet a stranger to moderation. Trueblood has an addictive nature he can’t shake.

He speaks to his sister on the phone 10 to 15 times a day. His favorite TV show is “Golden Girls,” he admits with a laugh, and he owns every season. His one-room apartment is a disheveled library, with high stacks of books on his nightstand, his floor, his dresser.

Reading, he feels, gives him power. He stores the facts he reads away in his mind and drops them in conversation with ease.

He likes history best. He thinks about the earliest accounts of running and can launch into the story of the first marathon without hesitation. “The Persians were attacking the Greeks back in 490 B.C. ...” he’ll begin. An Athenian runner was sent to deliver the news to Sparta, a route 26-miles long. Sometimes on a run, he’ll picture himself as a running messenger. Wes, we need you to take this message to Indianapolis. Be back in a few days. What job could be better?

The incessant chatter in his mind began when he was 13. The marijuana followed shortly after. Trueblood turned to harder drugs in high school, the only way he knew to ease his overactive mind. He enrolled at Indiana University in 1999, but didn’t last long. After troubles with the police and poor grades, he was kicked out.

Trueblood spent the next few years of his life jobless, sleeping on and off his mom’s couch, on a $300-a-day habit. His list of drugs included cocaine, heroin, meth, oxycotin, and morphine. But his favorite was a speedball — a mix of an opiate and amphetamine.

To maintain his lifestyle, he stole from his grandmother’s church group and snuck change from his niece’s piggy bank. He hustled drugs, including Adderall to stressed college students in the library, making a $5 profit per pill.

His sister, Wendy Miller, knew Trueblood better than anyone. Helplessly, she watched as her brother’s addiction transformed him into someone even she couldn’t recognize.

The breaking point for her came when Trueblood stole her pain medicine after she had surgery. Until then, she had not turned her back on her brother. But this had gone too far.

“I’m done,” she told him over the phone. “Don’t come back to my house. I love you, but I’m done.”

Cut off from his family, Trueblood checked into rehab and stayed for five months.

He felt safe in the structured world of rehab. But less than 48 hours after he left, Trueblood was already drowning in the anxiety of freedom. He was stuck — he couldn’t live in rehab the rest of his life, yet he couldn’t live in a place rife with beer cans and joints around every corner.

It was a couple weeks before Christmas in 2007 when Trueblood, then 27 years old, made his decision. He picked up the phone and called his sister in Evansville.

“I’m going to kill myself,” he said. “I love you. Goodbye.” Click.

He popped pill after pill — an anti-anxiety drug called Klonopin — and washed them down with Budweiser. He hopped into his light blue Ford Escort and took off, heading nowhere fast. Then he blacked out.

Minutes, maybe hours later, Trueblood awoke in a ditch. He couldn’t remember flipping his car or climbing out of it. He had no idea how he managed to escape the Escort, but there he stood, watching the wreckage he created as if a stranger in his own life. Not only had he survived, he had emerged without a single cut on his body.

As he stared at the car, he remembered the can of Budweiser he put in the cup holder before leaving his house. It was probably still there, he thought.

Still intoxicated, he waited for his world to stop spinning, then reached his hand through the broken window to pop the tab.

• • •

By five in the afternoon, Trueblood feels antsy. Hours have passed since his last run. He needs another release.

Soon his friends Scott Breeden and Emily Weisbard jog into the parking lot of his apartment complex. Clad in sleek black running tights, lightweight shoes, hats, and gloves, they are ready to take on the below-freezing temperature. The group begins their second six-miler of the day, eager to get warm, while the sun sets over Bloomington.

A few miles in, a skateboarder flies through an alley at the same moment the runners begin to cross it.

Breeden reacts first, halting and jutting his right arm out to stop Trueblood, who was closest to the boarder. The teen comes to a stop in front of them, jumps off his board and apologizes.

A fluke injury from a skateboard accident, or any other mishap, holds serious implications for Trueblood.

While he hasn’t gotten high from drugs in over three years, Trueblood is still an addict. His sister knows it, his girlfriend knows it, his friends know it. But Trueblood knows better than anyone. He’s addicted to running.

If he can’t run a day, he’s irritable, tense, short with people. He often finds himself lying about running to keep people from thinking he has a problem. He runs in the morning and at night, in ice storms and heat waves, deep in the woods or on city streets.

With addictions come tough withdrawals. So far, he’s been lucky to remain healthy in a sport where overuse injuries are the norm. But any minor ache sets him on alert-mode. Oh God, is this something that could debilitate me for a month?

No one knows what will happen should Trueblood get hurt. Maybe he’d take up swimming. He’d lift weights. He’d rely on the support of his family and friends, like he’d done before. But it would undoubtedly be devastating. He would always be thinking about running.

The three runners continue on their route, just a few miles in. They keep the topics light this time, referencing Seinfeld episodes and planning their next meals. Sometimes, the runs get too painful to talk, and those become the best memories. The runners feed off pain.

“Of course you have to hurt, but the reward is so much greater,” Trueblood says.

As his feet fly across the sidewalk, a Road I.D. clings to his shoe — a tag that identifies him in case of an accident. His name, his sister’s name, and his mom’s name are engraved on it, along with a favorite quote: “Pain is God’s greatest gift to man.”

• • •

It’s one of those moments that would haunt him years later.

Somehow, Trueblood had escaped from his wrangled car without a scratch, but there he was on the outside, reaching back in for his beer. A piece of glass slashed the palm of his hand. Blood gushed out of the inch-long wound. His only scar from the accident.

Bloody and intoxicated, he called his grandmother to pick him up, and it wasn’t long before Trueblood was back at his mom’s house, hiding from the police. His eyes were wide and vacant - drugs had taken over his body.

When the police arrived, the addict snapped. They were there to help, they told him. They didn’t want to arrest him, they wanted to take him to the hospital. But he didn’t want their help. He didn’t want anyone’s help.

Even his mom tried to calm him, but when the two locked eyes, Trueblood looked as if he didn’t know her.

“Wes, it’s Mom,” Vicki Trueblood pleaded. He just wanted to be alone. He barricaded himself inside his bedroom by shoving a queen-sized mattress against the door, and threatened to kill himself.

Several hours passed before Trueblood agreed to be driven to the hospital, where he was given a psychiatric evaluation and mild narcotics to relieve the throbbing of his hand.

Soon after he was released from the hospital, he went with his sister to Evansville in search of a job and an ounce of stability. But he couldn’t escape his suicidal thoughts. They still lurked. He told his sister, who drove him back to the nearest hospital.

That’s where Trueblood got back on his feet.

It was 1 a.m., and inside his hospital room he stared into darkness. It was almost impossible to sleep when coming down off drugs. Hours earlier he had asked his doctor for Tylenol PM. Absolutely not, the doctor replied.

So Trueblood was left alone with his thoughts.

I want to feel good.

Without drugs, Trueblood couldn’t remember how to feel OK in the world.

What has made me feel good? What has quieted my brain? What has made me not so insecure?

Then he remembered. When he was younger, he ran. He enjoyed the simple, rhythmic pounding of his feet against the pavement or trails, propelled by the engine inside his body. Running calmed him.

He had talent, too. In middle school, he ran a sub-five-minute mile. As a freshman at Bloomington High School South, he was consistently one of the top runners. He had won races and broken records. But he’d quit running after his sophomore year, choosing drugs instead.

Trueblood remembered feeling good after every run. He decided he wanted that feeling right there in the hospital room.

He got out of bed and stood on the floor, then began running in place. The motion seemed foreign to his body that had grown soft and carried an extra 60 pounds. But the addict was running.

He continued to run until he couldn’t any longer — no more than 20 minutes. His legs burned and his heart pounded against his chest, but he felt lighter. He had cleansed himself of the internal energy that was bogging him down, the tireless thoughts that swelled inside his head. He was filled with hope.

If I can run, I’ll feel good, he thought.

And if I can run enough, I can feel good all day. This is it. This is what I need to do.

• • •

The runners zigzag through town, past college houses with beer cans strewn across the yard, past Big Red Liquors, past bars at the start of happy hour. Silent temptations in every step.

A few miles in, Trueblood, Weisbard, and Breeden reach the downtown square. They stop across the street from the Indiana Running Company, a store they frequent, to talk to a friend.

“How far are you guys going?” She asks them.

“Just six,” Trueblood replies. “We did six earlier so we’re doing six now. Messing around, getting some mileage in. Talk to you later, Tracy.” The pounding of their feet on the sidewalk continues.

Both Breeden and Weisbard are ultra-marathoners, who run races longer than the marathon length of 26.2 miles. Trueblood is proud to fit in with these accomplished runners. In December, he reached his primary goal since returning to the sport: finishing in the top 10 at the Tecumseh Marathon. He placed seventh.

Trueblood had experienced excruciating pain before — coming down off drugs, for instance. But nothing in his life had ever hurt worse than that marathon. Yet, at the same time, it was the sweetest feeling. He was finally there — a competitive distance runner.

With the marathon down, he now looks to longer distances. He plans to run a 50-mile race next year.

Addicts, Trueblood says, move at the speed of pain. It was the pain of hitting rock bottom that night in the hospital over three years ago that got him running. As soon as he left, he told his mom he was done with drugs and alcohol. This time was for real.

She had heard it too many times before.

“You’re going to have to show me,” she told him. So he did. Trueblood lived on her couch for a year, got a job, and began running. He went back to IU in 2008 to finish his degree in history, and graduated with a GPA just under 4.0 his last two years.

The running started slow, at 10 miles a week. He ran alone, too insecure about his out-of-shape body to seek running partners. Trueblood dreamed of a strong finish in the marathon and, eventually, an ultra-marathon. But he couldn’t train alone for very long. He needed someone’s help.

Enter Breeden. Nine years younger than Trueblood, he was already competitive in the national ultra-marathon scene. The two runners were acquaintances, but after Trueblood saw Breeden’s impressive finish at a race last year, he asked to run with him.

Their first one was an eight-miler on trails in sweltering heat. Now, a year later, the two run together almost every day. They’ve shared delusions by dehydration, countless heart to hearts, and a run they’ve dubbed “The Death March.”

Breeden knows he can count on Trueblood to run at the same time each day. Usually, he’ll run the same route, one they call “The Wes Loop.” He never cuts a run short.

“He always says if you go out to run six miles, why would you run 5.8,” Breeden says.

This year, on his anniversary of being sober, Trueblood wrote on Facebook: “Three years ago today I changed.” He had not taken drugs since the night of the wreck.

Those who meet him now could never guess his past. Trueblood’s energetic, upbeat personality makes people smile. His kind eyes make them want to share their hardships with him, never expecting he has plenty of his own as well.

He returned to his true self, the Wes his family longed to meet again. Trueblood’s sister commented on his wall: “Glad to have my brother back.”

Miller knows her brother swapped one addiction for another, but she doesn’t care.

“He can be addicted to running all he wants,” she says. “He’s pure Wes when he’s running.”

Trueblood’s mom has watched his love for running evolve through the years. As a teenager, he felt pressured by others’ high expectations, and running lost its luster. Now, he runs with sheer passion.

“He has a very strong desire to be free,” Vicki Trueblood says. “When he runs, he’s free.”

In her eyes, Trueblood’s battle with drugs was just part of his life plan. Even when he hit bottom, when he thought his life was over, his mom knew he’d find his way out.

“He’s got a lot of heart and a lot of spirit,” she says. “I always hoped that it got directed in the right way.”

• • •

The demons can’t keep up when he’s running. With his heart pounding and endorphins flowing, his muddled mind clears itself of the negative thoughts. Trueblood is left alone.

Sometimes when he runs, he thinks about his next race, imagining himself on track for a great finish. Stay up straight, he tells himself when he gets tired. Keep breathing. He thinks about his hunter ancestors or the Greeks who ran to deliver messages. This was how they retrieved their most basic necessities. This was how they survived.

Trueblood runs believing it saved his life. He also runs knowing he traded one addiction for another. He doesn’t like being dependent, but says it’s a fact of his life. And if he must be dependent on something, he’s happy it’s running.

At the end of every run, the internal battle continues. Trueblood can’t outrun something inside of him, because when he stops, the demons catch up. So he’ll just keep running, as much as he can, for the rest of his life. It’s all he knows to do.

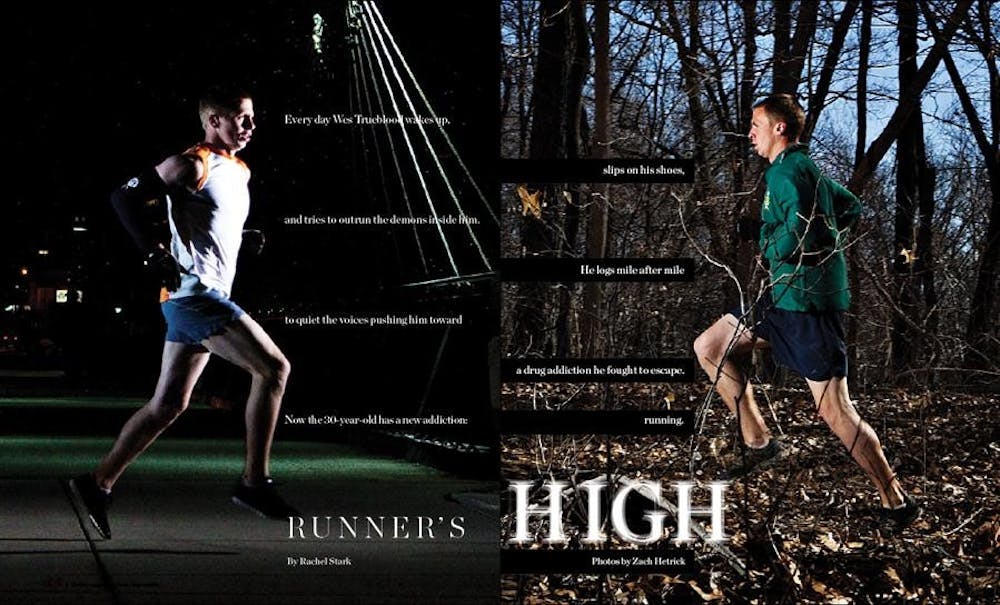

Runner's High

Wes Trueblood gives up his addiction to drugs for running

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe