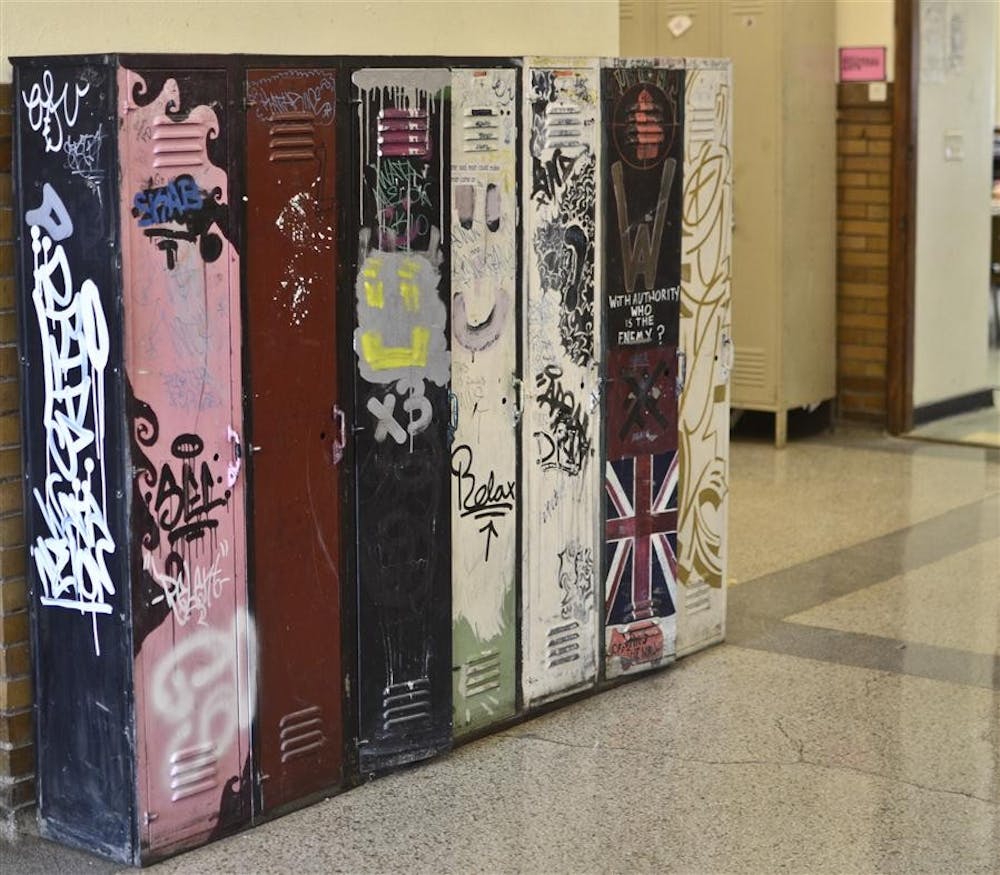

A dog, graffitied lockers and kids playing in halls are not typically found in a school scene. However, the lack of letter grades, standardized curriculum and official sports teams make the Harmony School an unorthodox alternative to traditional education.

Three blocks south of Jordan Hall, the private alternative school aims to foster an environment of free expression that teaches students to become self-motivated and civically-engaged individuals.

Annie Dill was one of these Harmony students who decided to come to IU — a choice many Harmony students make.

“It was really just like going to school with a family,” Dill said of the 15 years she spent as a Harmony student.

Harmony students named several features of the school as influences upon their IU careers. Among these are senior projects, close interaction between teachers and students, and small classes.

To graduate, each senior must design and execute a semester-long graduation project. It is an opportunity for them to explore an area of interest before leaving high school.

Dill participated in a 10-month-long exchange program in South Korea, where she studied translation.

“I translated books and songs from Korean to English,” Dill said. “I wrote a children’s book in English, translated it to Korean and then illustrated it.”

Dill said her 10 months abroad were not only a time to make friends from different parts of the world, but a time to discover her limits and her potential for the future.

Chelsea Korth, a Ph.D. student in education policy at IU, lived in Dublin, Ireland, where she studied Irish history for two-and-a-half months.

“Living basically alone when you’re 18 in Europe, independence is thrust upon you pretty significantly,” Korth said. “I took the bus, made myself my own meals and had to get myself to class everyday.”

Experiences such as these taught students skills not found in a traditional classroom.

“Those four months allowed me to do something that I never would have done in public school,” said junior Riley Voss, who interned as a lobbyist for a nonprofit agency in Washington, D.C.

Harmony students also credited close teacher-student interactions as being very important to their current IU careers.

Sallyann Murphey, Harmony’s high-school coordinator and social studies teacher, said the relationship between students and teachers is familial, like aunts and uncles. Students call teachers by their first names and have their home phone numbers.

Dill said the closeness with teachers was very comforting.

“Harmony was like a family, including the teachers,” Dill said. “I just felt like I could talk to them about anything.”

Dill said that kind of relationship makes her feel comfortable with her professors now.

Senior Sahar Pastel-Daneshgar agreed.

“Harmony really made me able to talk to people of any age,” Pastel-Daneshgar said. “I am not worried about trying to talk to (professors) because I don’t think of them as unapproachable figures. At Harmony, they foster that kind of atmosphere, one where you can approach or talk to anyone.”

Similarly to the teacher-student relationships, the classroom environment at Harmony differs from that of many traditional schools. In Murphey’s classes, for example, students do not sit at desks. Instead, they form a circle with their chairs and participate in group discussion.

“I need to be able to make eye contact with everybody very easily,” she said.

Murphey said she uses the Socratic method, which Dill said is similar to discussion classes at IU.

“I tend to feel that the professors aren’t talking at us, they’re trying to probe us for discussion,” Dill said. “At Harmony, they would do that a lot. They tried to probe us for questions rather than force answers down our throat. “Voss, who is now the vice president of programming for the Union Board, vice president of business development for Students Offering Services and a member of the Pi Kappa Phi

wfraternity, said the small classroom environment at Harmony was helpful to his current success at IU.

“The classrooms were small,” Voss said. “You were able to ask questions and have group discussion, and I think that really helped me as far as where I am now.”

Dill said the most valuable trait she gained was a sense of self-motivation — something the students agreed prepared them for life after Harmony.

“I can’t say whether I was more prepared to come to IU with Harmony than I would have been with a public school, but I certainly was more prepared for different parts of being in school,” he said. “There’s a lot more to being a college student than being in class, and I think I was better prepared for some of those things.”

However, other aspects of college were more of an adjustment for Harmony students than for others.

“I was in a high school with between 80 and 90 people,” Voss said. “There are 40,000 people at IU. In the fraternity, I live with more people than I went to high school with.”

Dill said that, even in a lecture hall with more than 150 students, she sometimes still felt alone. She missed the closeness of her classes at Harmony.

Adjusting to grades was another challenge, Dill said.

“It was really kind of nerve-wracking when I got my first letter grade,” Dill said. “At the end of the semester, that letter is everything. It’s kind of a weird feeling, working toward getting a letter instead of doing your best personally.”

According to the Harmony School website, grades are not used as a means of evaluation. Instead, students write self-assessments at mid-semester. Teachers write evaluative comments on these papers and then send them home to the parents. Tests and quizzes are often graded with percentages, but letter grades and grade-point averages are not given.

Although adjusting to IU was challenging in some aspects for Harmony students, Voss said all students undergo a transition process when entering college.

“Nobody is ever 100-percent ready to come to college,” Voss said. “I don’t think I’m any less prepared than anybody else. “

Harmony students said they received a high level of education even though Harmony’s curriculum is state-accredited, not state-mandated.

“Because of No Child Left Behind, (state-mandated schools) teach for the test,” Voss said. “A lot of education is restricted by what’s going to be on ISTEP, college entrance exams and so forth.”

Voss said the flexibility of Harmony was beneficial.

“That’s what I got out of the school, that more broad education,” he said. “They balance it out better.”

For Steve “Roc” Bonchek, an IU alumnus who founded the Harmony School in 1974, the lack of government-mandated curriculum was pivotal to achieving his goal for the school.

“The school was founded at the time of Watergate,” Murphey said. “Watergate was such an incredible shock to people. Roc wanted to put in place a school that would raise a citizen who would fully participate in a democratic society.”

Today, Harmony’s goal remains the same.

“Our goal is to educate students to be fully contributing members of a democratic society as adults, to produce graduates who are lifelong learners, independent learners, to educate students so that they can learn whatever they need to learn,” Murphey said.

Even after leaving the school, the students said they never lose their Harmony identity.

“There is a popular phrase amongst the students — ‘Harmony-born and Harmony-bred, and when you’re gone you’re Harmony-dead,’” Murphey said.

Harmony School offers alternative to traditional education

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe