Fritz Lieber sits at the front of his classroom in the Hutton Honors College. His tan corduroys wrinkle in his chair, edging over his tennis shoes. His tortoise shell glasses glint in the snowy sunshine slipping in. In this room, he isn't going to teach chemistry or calculus. He's not going to lecture about proper placement for commas. What he's been studying is entirely different, something with no right answer and no certain formula — happiness.

Lieber has been studying it since 1980. In this class — “The Pursuit of Happiness” — his students study everything from the Bible and Aristotle to Emily Dickinson and Beethoven searching for the answers no one has.

As college students, we’re just starting our own journeys. We don’t have all the answers.

This is the story of three people who have gotten close — a groundskeeper, a funeral director, and a professor. They’ve seen hardships most of us haven’t, but from the very bottom, each found something elusive and rare — their secret to happiness.

***

Natalie Childers was boot-deep in leaves and brush, digging near the Jordan River in the shadow of Ballantine.

She bent over and picked through the sticks.

“Just the big ones,” she says, tossing them up the banks. She and her supervisor were working to manicure the area they oversee as campus groundskeepers.

She smiled in the cold sunlight. This — finally — was where she was meant to be.

The last time she was really happy, she was 16. It was the end of March, and she and her dad had gone camping. They’d gone fishing, and they’d climbed waterfalls. Under the stars, they’d talked about things they never had before.

“Dad, if you die, I want this camper,” she says. “If we died now, this would be our heaven.”

When she went to sleep, it was the happiest day of her life.

The next day, Natalie didn’t go to church with her dad. He had narcolepsy, and she wasn’t there to keep him awake at the wheel.

When she saw her mom and brother, she knew something had happened. It was April 1, and she thought it was a joke. It wasn’t. Her dad was dead. The words they’d spoken weighed on her. The guilt she felt did too.

In her grief, she began researching Native American beliefs — part of her mother’s heritage. When she was outside, the pain all melted away. She would play basketball all night — something she and her dad used to do — almost until she was too tired to stand. She felt like he was there.

But when she was forced to sit still at school, her grief came back.

Her happiest day and saddest day were wrapped up tightly, inseparable. It would take years to recover. She didn’t know it then, but the seed of her happiness had already been planted.

***

Most of David Shirley’s professional life is made of quiet moments. They’re moments when, sitting across from people surrounded by coffin samples, they can’t collect their thoughts. They’re moments when there’s quiet sniffling at a graveside. And they’re moments when the halls of Allen Funeral Home, where David is a funeral director, are quiet, waiting for the next person to call.

David is the person whose life is surrounded by the worst moments of other people’s lives. His business is easing their pain, building from their grief. From the outside, every day can seem drenched in death.

Most days, though, he sees a light. The son and daughter of a 93-year-old woman will come in and talk on and on about how wonderful their mother was. At the gravesite, just after burying his mother, an only son will turn to David. He’ll shake his hand and tell him how great all the arrangements David was able to put together were. Those are the best days.

But David hasn’t always been the comforter. He’s been the man at the graveside before, too, the man dealing with loss.

Twenty years ago, at Christmas, he had a daughter, but she died at birth.

“It was 20 years ago,” he says. “Sometimes it feels like yesterday. Some days it feels like 100 years ago. If you have people in your life, you’re going to have loss.”

His divorce followed. He felt like a failure. He had to find a way back.

David has a theory that there’s the event, and then there’s a gap. In the gap, you get to choose how you react. What you do in the gap determines what comes next.

“There’s no one step,” he says. “Although each began with steps.”

There, in the darkness of the gap, he chose to keep walking.

***

Lieber doesn’t think about his bad times like most other people do. He’s studied therapy and has been a therapist, and sometimes, when he’s feeling down, he’ll analyze himself.

“Sometimes I ask myself, ‘Is this the depression talking?’” he says. It’s how he would talk to his patients.

Most of the time, he doesn’t think about happiness like the rest of us, either. When he thinks about it, he looks at it as an idea — as something with a history, a question other people have asked before.

“I like the idea of happiness being more than just a feeling,” he says. “It is a feeling, but it can be an idea and attitude that relates to the whole life, not just a moment of it.”

Most of the time, though, he doesn’t think about it. He lives it. He goes home and writes letters to friends and old students. He plays with his cat, Miaki, and talks to his partner when he gets home from teaching history at Indiana State University. He likes to cook — fresh vegetables, fish, and chicken are his favorites — and he loves drinking wine with friends.

Outside the classroom, he doesn’t wear it on his sleeve, and it doesn’t haunt his every thought. He just is happy.

***

Natalie’s secret to happiness rose from disaster, just as she did. She was working in the IU Art Museum as a security guard when the museum underwent construction. She had to lose hours or transfer to the grounds crew. She was the only one who switched.

Then, tornados hit, and trees came crashing down around campus. To her, it was a miracle. Because she had worked so hard and they liked her work so much, they wanted to keep her.

Every season brought the ache of new muscles, but she loved it. Being outside, she felt like she did shooting baskets after her dad died. She belonged.

“I have a strange belief that some people have more of an animal side,” she says. “I believe that for me.”

She bonded with the men she worked with, teasing them and playing pranks just like they did to her. Her supervisor, Tommy, even taught her to hunt. That was something her dad always promised her he would do.

Tommy said she was a natural, and this year, they killed seven deer. He strung the antler of her first on a necklace, and she wears it every day.

She’s lost 70 pounds, and she’s thinking about joining the National Guard, a tribute to her dad, who was a Green Beret. She could also see herself starting her own landscape business.

This day — the quiet, cool morning by Ballantine — she’s where she belongs. She bent down again to pick up more cut branches, tossing them up the bank.

At the end of the day, she’ll be tired. Her back will ache. But the sweat and pain are her miracle. From her dad and the tornado to here, she’s found her place.

“This is my home away from home,” she says.

***

There’s a framed quote that hangs above David’s desk.

“Life has, indeed, many ills, but the mind that views every object in its most cheering aspect, and every doubtful dispensation as replete with latent good, bears within itself a powerful and perpetual antidote.”

It’s the one thing he looks at when he’s having a hard day, but he hasn’t had to look at it much lately. Right now, he knows, he’s in the happiest time of his life.

He has three children, a 17-year-old and 7-year-old twins, and they amaze him every day. He’s with a wonderful woman, and she has three kids, too. They look like the Brady Bunch when they eat at a restaurant. He’s an avid cyclist, and he coaches a Little Five team.

Sometimes, when he sees college students, he does think about his daughter. She would be their age now, he knows. But, he remembers, if that hadn’t happened, who knows where he would be. He might not have the children he has now. It might all be different.

On his bad days — even his worst days — he still hangs on to his own secret. When he’s sitting across from the parents making arrangements for the 18-year-old son they hugged that morning, he knows.

That flat tire last week wasn’t too bad. The kids being loud last night isn’t too much. The problems of the past melt away. None of them seem that important in the scheme of it.

“Everything else is pretty much a hangnail,” he says.

***

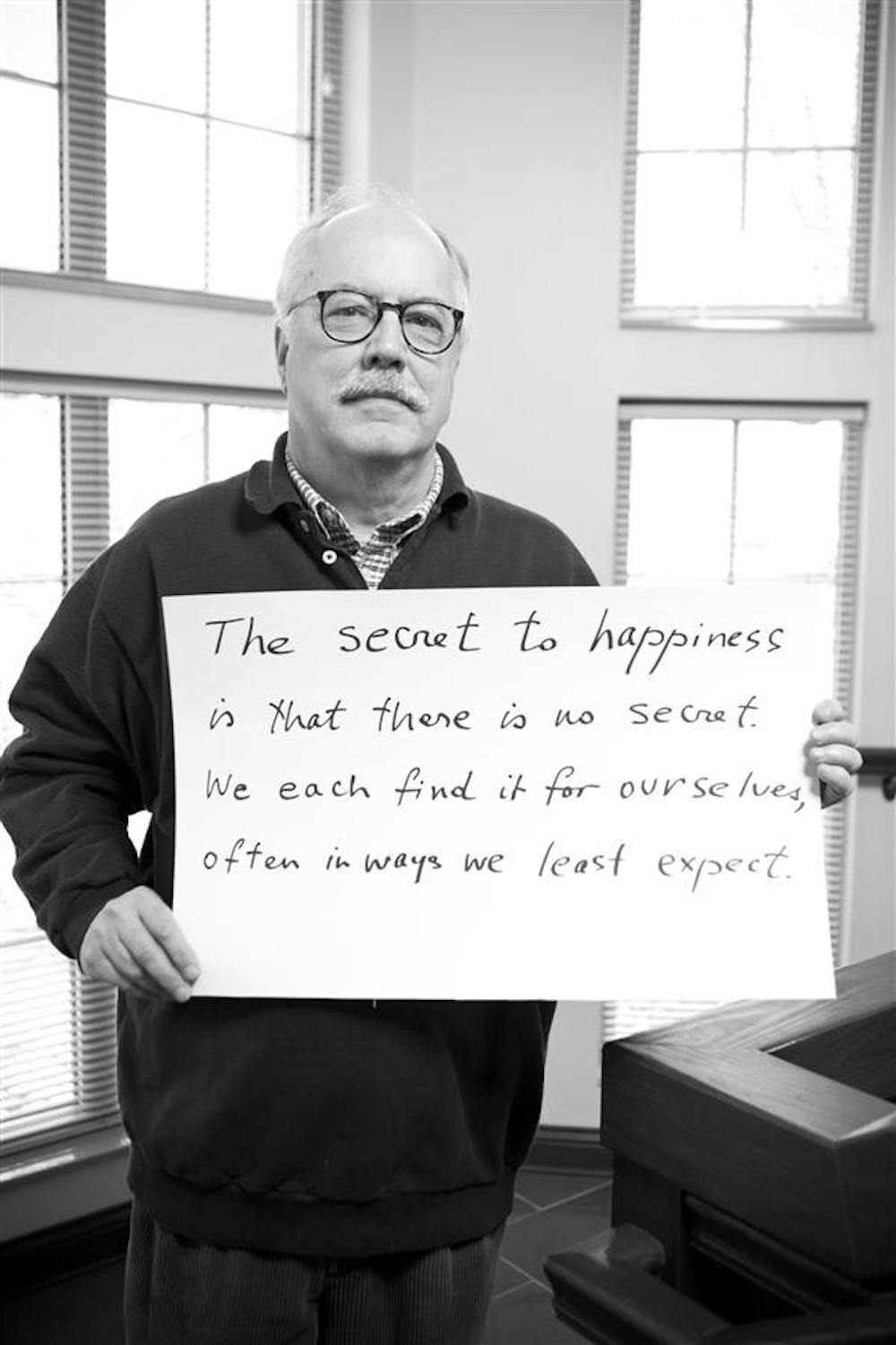

On the stairs of the Hutton Honors College, just before his class, Lieber is asked a question. What’s your secret to happiness?

He has years of study behind him. There’s the teachings of the Dalai Lama, Camus, Mill, and Kant. There’s his cat and his partner, cooking, and writing. There’s what his students have to say.

It’s a lifetime of choices, of knowing.

“The secret to happiness is that there is no secret,” he writes. “We all must find it on our own.”

Their secrets to happiness

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe