Every day, on every corner of campus, students throw away little pieces of their lives.

We discard Jimmy John’s sandwich wrappers in the underbrush of Dunn Woods. We drop crushed beer cans in the mud of the tailgate fields. We accidentally leave textbooks in empty classrooms. From Dunn Meadow to Memorial Stadium, we leave bicycles, laptops, Papa John’s Pizza boxes, dinosaur toys, dildos, Halloween masks, underwear, Mickey Mouse ears.

In the grass, we leave condoms, some used, others still untouched in their wrappers. In the trees, we pin love notes — Valentine’s Day messages that will never be delivered.

In the dumpsters outside the School of Fine Arts, we abandon sculptures deemed unworthy. In the School of Music, frustration consumes us and we smash our violins and then throw them on the ground outside.

Every day, IU-Bloomington students discard about 186,000 pounds of garbage. Every year, the University dedicates thousands of man-hours and spends thousands of dollars to keep it from burying us.

The campus workers who collect what we throw away know us through our trash. Desire, ambition, sloth, love, hunger, hope, disappointment — they see all of it in the things we leave behind. They pick up what we have forgotten, and then they make it

disappear.

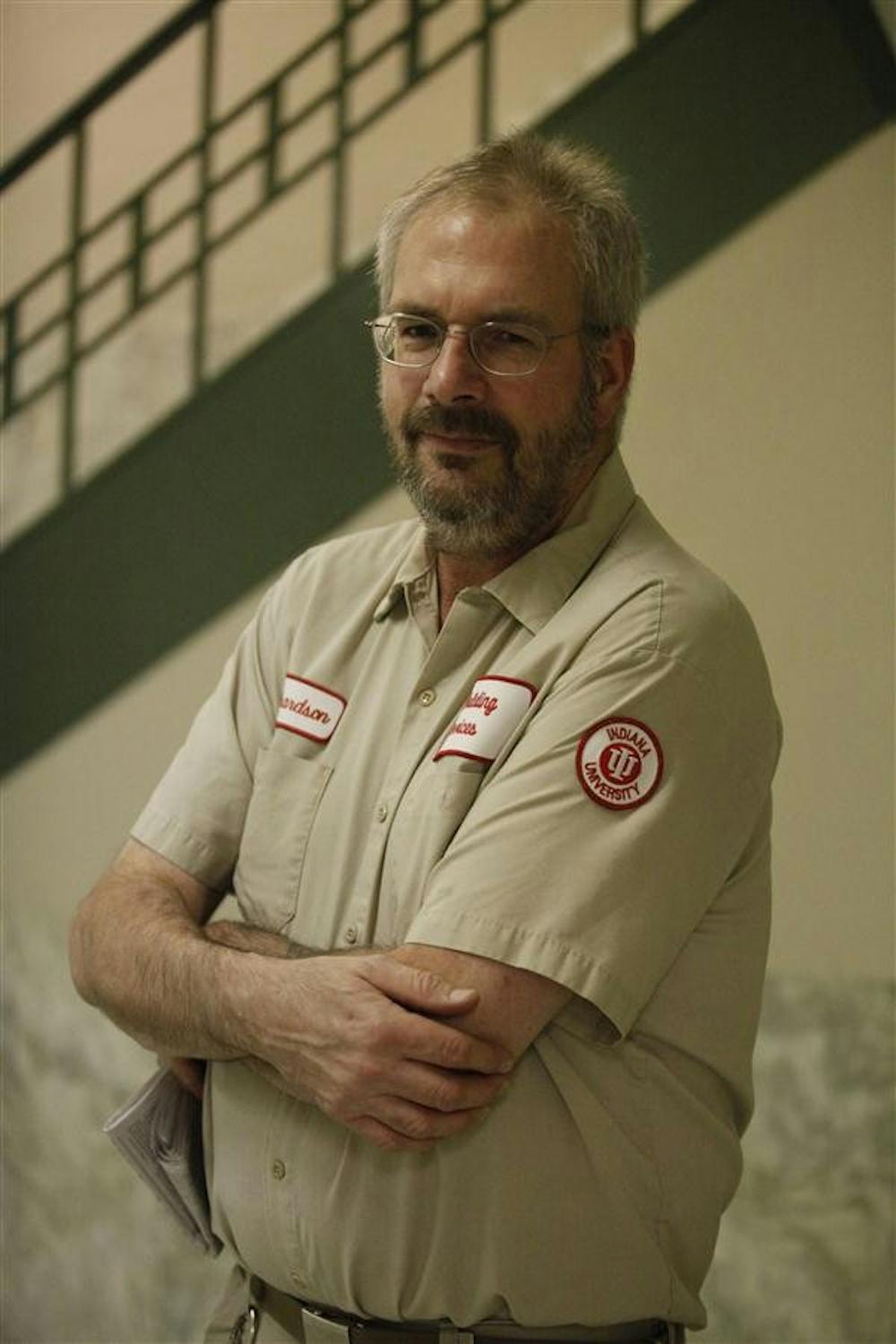

Mike Girvin wages a perpetual war on litter. As a Campus Division manager, he heads the team of grounds keepers charged with keeping the Bloomington campus beautiful.

Others clean the interiors of the buildings. Girvin’s crews tend to what’s outside. They plant flowers and pull weeds. They mulch and prune and mow. They also devote 11,000 man-hours each year to trash.

“On a typical day, we probably pick up 1,500 pounds of trash,” Girvin says.

Some of it they pull from trashcans and Dumpsters. Some they find scattered throughout the grounds, junking up their tulips and neatly mowed lawns.

Girvin, 55, has a bachelors degree from IU in outdoor recreation. He doesn’t enjoy being a glorified trash collector. He would rather his crews could spend their time planting more tulips. He wishes more of them would think about the workers who have to deal with what they drop on the ground.

He describes himself as “a worker bee.” Although he directs his crews from behind a desk, he often wanders campus, making sure everything is pristine. Once, he was outside picking up trash when a student called out to him.

“God, I bet you wish you’d gotten a college education,” the student said.

“Indiana University,” Girvin answered. “Class of ‘79.”

In his job, he surveys both the mundane and the odd in student habits. Studying their rubbish, he sees patterns. Certain areas of the 2,000-acre campus are extra trashy. The grounds surrounding McNutt and Briscoe quads are usually dirty. Forest Quad, a past hotspot, seems to be cleaner this year. Central campus, around Ballantine Hall, is usually heavily littered. Finals week breeds more mess.

Each bit of trash tells him about students. The Snickers wrappers reveal our cravings. The blow-up dolls, left in the branches of trees, speak to other desires.

“You find obscene things,” says Girvin, back at his desk. He pauses. “How do I put it delicately?” Another pause. “Sexual aids. Course, a bajillion condoms that you find.”

Cellphones, wallets and intact electronics are returned to their owners whenever possible. But when they find an item that is notably odd, the team sometimes snaps a picture or even saves it. They keep these artifacts in a makeshift museum scattered between different buildings. “The Hall of Shame,” Girvin calls it.

When he and his crews head out on their rounds, they say they’re “going out trashing.” Sometimes, the things they find give Girvin pause. He wonders about the last hands that held them. He imagines the rage behind those smashed violins his crews find

outside the music school. He asks what leads someone to tack his or her love notes to a tree. Every February, they find more of the forlorn Valentines.

At least the trash on a college campus is interesting, he points out. Even artistic. He experiences rare moments of incredulity.

Once, during a campus inspection, Girvin found a small sculpture at the base of the Sample Gates. A tiny man, stretched out on a tiny lounge chair, with a palm tree swaying overhead — all of it made out of clay.

When he tried to pick it up, it fell apart in his hands.

Some basic terminology:

The official term for trash is “municipal solid waste,” and it’s defined as everything we throw away that isn’t industrial, hazardous or left over from construction.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency’s most recent report, Americans generated 4.43 pounds of trash per person per day in 2010. That’s 250 million tons of trash in America that year.

At IU, the trash is sorted and taken to a transfer station before it’s buried in a landfill in Terre Haute.

Those who clean up the trash will never win the battle. More is constantly being created. But without their efforts, the campus would quickly look like a garbage heap.

On a chilly weekday morning, Mike Montgomery trashes the grounds between Bryan Hall and the Maurer School of Law. In one hand he holds a five-gallon bucket, and in the other he grasps a long stick with a claw on the end.

“We try to keep it looking like Disney World around here,” Montgomery says.

The job makes Montgomery cynical. To him, students who leave those items don’t respect the campus. Broken glass, dangerous for workers, makes him angry. And he’s no longer surprised when they find bottles of urine. Sometimes, when they’re mowing around the dorms first thing in the morning, the bottles rain down from windows above.

“Of course, if you’re mowing a little bit too early, maybe you should get a bottle of piss thrown at your head,” he says.

He can acknowledge that students’ habits aren’t all bad.

“Actually, once in a while we’ll see a student that will stop and pick something up and put it in the trash can, and we usually thank them,” he says.

Walking a path behind the law school, he digs through the weeds with his claw. He pulls up a spoon and drops it in his bucket.

“It’s a losing battle, but we try to fight it,” he says.

Montgomery, 56, is officially a gardener. But he’s spent a portion of each of his 24 years on this job picking up trash. The groundskeepers used to devote two-and-a-half hours every Monday and Friday to picking up trash. Now, with fewer full-time employees and a record number of students, the crews are fighting more trash with fewer resources.

“It’s kind of degrading that we have to come out here and do this. We didn’t put any of this trash here,” he says. “But we have to keep the place looking sharp, so I can see that it has to happen.”

Years ago, he was on a team that cleaned the stadium.

“Why in the hell do people just throw it under their seat?” he asks. “Why, when there’s trash cans around, and recycling bins and such these days, why not utilize those?”

Snapping his claw and shrugging off the cold, Montgomery heads toward the Kirkwood Observatory. He circles the building and stops at a sunken window in back. He peers in and, with his claw, extracts a faded Sunkist soda bottle from the shadows of the window’s stony well.

“Look at this little hideaway, this is cute,” he says. “Isn’t this nice? It’s a little depository for trash. This was all planned by someone.”

He moves to the well of the next window.

“Look at this,” he says, pulling up a tangled mess of twine. “Where do you think that came from? That came from a bale of straw or seeding and they just said ‘to hell with it, leave it. We’ll get the grunts to get it.”

Finally, inside a third window cubby, Montgomery stumbles upon a small mystery. It looks like a yogurt cup, but it’s wrapped in tape marked with a camouflage pattern. He picks it up with the claw and inspects it. Why, he wonders, would someone camouflage a cup? What’s waiting inside?

Montgomery shakes his head, laughs and drops the mystery in his bucket.

“I don’t even wanna open that.”

Trash is humanity’s trail.

Pompeiian tombs doubled as garbage dumps. Egyptians left circles of trash mounds buried under sand dunes. Native American garbage heaps have become Everglades tree islands. The eighth hill of ancient Rome is made up of ancient trash.

Archaeologists sift through antediluvian piles of garbage — artwork, animal bones, jewelry — to decipher the habits of long-dead civilizations. What they ate. What they bought. The residue of their daily lives.

Centuries from now, if future archaeologists decide to comb through the trashy remnants of this campus, what will they think of us? What will they make of our obsession with Pop Tarts? Our attachment to blow-up dolls?

Late on a Monday night, a team from building services sweeps through the ground floor of Ballantine Hall. They begin west of the giant globe, pulling their cleaning carts and vacuums and garbage cans, then hit the empty classrooms one by one.

At the rear of the caravan of cleaning, Mark Richardson and his broom push a wide swath of dust and paper scraps across the floor. He doesn’t usually see students on this shift. Unlike some, Richardson does not resent the students for the messes they make. He tries not to wonder why they don’t pick things up.

“I don’t really worry too much about the students,” he says as he pulls down a blizzard of Kaplan fliers from the corkboards lining the hall. “I figure they’ve got enough stuff on their minds to do. I can’t expect them to treat it like maybe their home or something like that.”

He pauses.

“It’d be nice, but it’s not always possible.”

Richardson is 56. He likes the hours and benefits of his University job, but wishes it were more challenging. As he moves through his shift, he sets goals for himself — like improving his skill on the power washer he uses to clean the floors and walls of the bathrooms.

“It’s a craft,” Richardson says. “You learn how to do it, then you continually work on finessing your own ability. It’s probably like writing.”

The lecture hall in 013 is always trashed out. Tuesdays, after the Beatles class, are the worst. But tonight is bad enough, and the team empties the aisle of Pop Tart wrappers and empty water bottles. Despite the signs barring food and drink, the litter on the ground seems to be made up of students’ last meals.

“I tell people ‘I work in higher education, but it’s not what you think,’” he says.

He shakes out his heavy broom with a click-click-click. Richardson’s version of Ballantine Hall exists at night, but he finds traces of the student world in the rooms he cleans — umbrellas, textbooks and notebooks he doesn’t think are ever returned to their owners.

He’s sweeping out another classroom near the end of a hall now. Other workers might look at what students leave behind and think they’re all wealthy, he says, but he knows that’s not always true. He remembers long nights and frenzied assignments from his time as a student at Indiana State University.

He imagines that when a student rushes out of the classroom, their mentality is different than it would be at home.

He shakes the broom again.

He bends over to pick up a cough drop near the front of the classroom and wonders, unusually, what distracted the student who left his wallet in the lecture hall tonight.

“When they’re in the classroom, they’re focused on the task at hand,” Richardson says. “They’re not really thinking about what type of stuff they’re shedding, what they’re leaving behind.”

He tosses the cough drop into the corner trash can, where it lands with a final thud.