How IU is taking the Master Plan from concept to concrete... and what students have to say about it

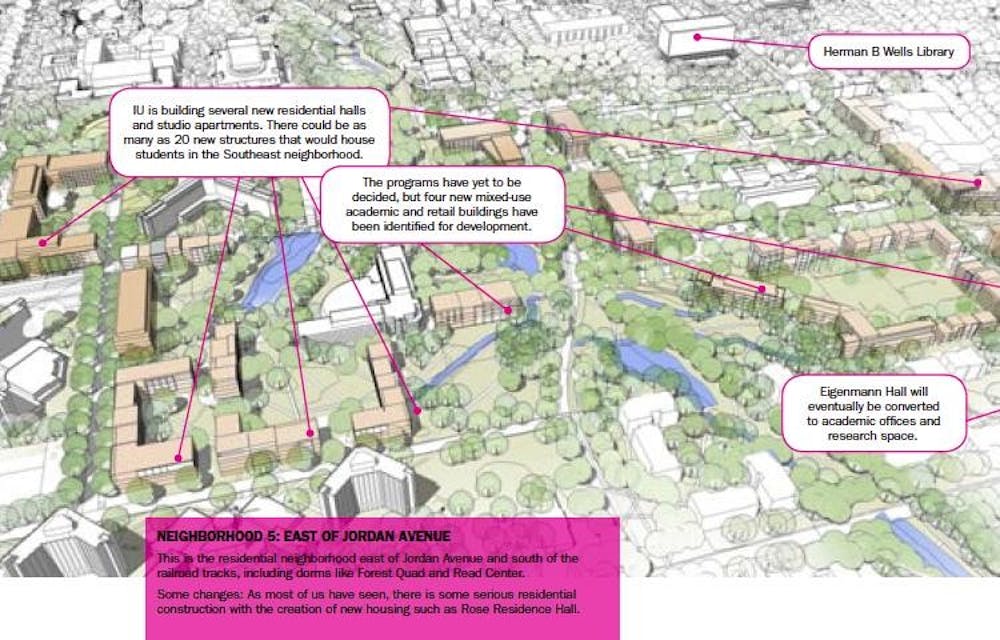

Campus reflects our college experience in pieces — the place where we first met someone who changed our life, saw a flyer that jump-started a love for an organization, or the classroom where we had that “aha” moment.For many of us, this campus is far more than just the buildings where we have our classes or the walking paths that get us there. It houses our memories and experiences for four years. But eventually we leave, taking a piece of IU with us. As we continue to change throughout our lives, our campus will do the same. We have our life plans. IU has its Master Plan. “President Michael McRobbie feels that if we are to progress, we need a plan. We need to know where we want to go in the next 20 to 25 years,” Paul Sullivan, deputy vice president for Capital Planning and Facilities at IU, says. The plan spans decades, so specific time frames for projects remain uncertain. Completion depends on gift money, as well as state grants and internal funding from IU. The wheels started turning in November 2005, when the Board of Trustees approved the creation of a plan. In February 2008, IU started a one year process to create the Master Plan with SmithGroupJJR, one of the largest architecture, engineering, and planning fir ms in the country. With the opportunity to create this Master Plan came great responsibility for the master planner, David King. After he was hired, Sullivan says one trustee told him, “No matter what you do, don’t screw this up.” “There is a lot of feeling that this is a gorgeous place, and we don’t want to lose any of that. And David has lived by that,” Sullivan says. “We knew of its importance as a historical place and as a vibrant university, so we were quite eager about the assignment,” King says. It was a moment for the University to step back and take a look at itself, King says. A chance to rehash the history and identity of IU in order to picture its future. “You can look at the institution and see where it’s been, what its physical characteristics are, and where it will be in 30 years, and that was the kind of timeline we were looking at,” King says. Collaboration was necessary before bringing out the hard hats. King and the rest of his team had to nail down what the administration, faculty, and students needed.Professor James Capshew, who teaches a course on the history and culture of IU, likes many of the changes the administrators are pushing for. “In general, it’s a positive change. But you need to have a broad range of input,” he says. “As long as they do that, things will be fine.” At the administrative level, there were regular committee meetings. The planners took a look at the 2007-2008 Student Vision of the Ideal College Environment Report. The students also told SmithGroupJJR their opinions at open houses hosted in dorms, libraries, and the Union. They marked up maps of campus with stickers, highlighting their favorite and least favorite places and everything else in between. “There was a lot of appreciation for the campus spaces and landscape, and they felt that some buildings weren’t as attractive as others in the historic core. Everyone always gives Ballantine a hard time,” SmithGroupJJR senior campus planner Mary Jukuri says. And while there were meetings that included student input, officials couldn’t provide specifics on the actual number of students included. In 2011, the IU Student Association commissioned a new VOICE Report to see how students felt about the Master Plan as well as other changes taking place on campus. Members of Union Board worked together with IUSA to gather opinions through surveys and meetings. “It’s absolutely necessary for students to figure out some way they can get involved on campus and have a say,” Union Board Vice Presidentfor Programming Riley Voss says. “Having a say is a fundamental aspect of what happens here.” Student leaders compiled and submitted a report to the administrators that detailed their findings including what students think about campus life and what they want to see changed. Some of the plan is already in action and affecting students’ daily lives. The hard hats, blocked walking paths, and sound of jackhammers in the morning are all key pieces to the Master Plan. Within the next five years, students will be able to see some significant changes with new construction on the corner of Jordan Avenue and Third Street. “We are also aiming to put Woodlawn Avenue through the railroad tracks, so it will run from the Union to Assembly Hall, really changing the structure of campus,” Sullivan says. But this isn’t “Extreme Makeover: Campus Edition.” Ty Pennington isn’t going to come bulldoze Ballantine. It’s more like “What Not to Wear” — a fresh haircut, a splash of makeup, and sophisticated clothes coming together to make a newer version of campus. Even as they greet new changes, students will have to say goodbye to some old favorites. The beloved Assembly Hall, which houses many memories, is up for demolition. Sullivan says the facility has a number of problems that he’s not sure can be adequately addressed. Because of the size of the project, nothing will happen to Assembly Hall until there is enough funding to support it. To see the new Assembly Hall, along with the rest of the campus changes, current students will have to come back as alumni. “Honestly, right now, it’s not affecting the students because a lot of them don’t even know it exists,” Panhellenic Association President Kendra Allenspach says. Allenspach believes the Master Plan needs to be made more public. “Although our IU experience is just for the four years we’re here, the University is going to go on after we leave and we need to do everything we can right now to make sure that it’s a thriving organization for the future,” she says. “Knowing and understanding the Master Plan will give more insight to the future of the University, and make them care a little more about how they spend their time here at IU and about making it a better place for future students.” She herself doesn’t know much about the Master Plan and its proposed changes, and says she feels left out of the conversation. “There’s a lot of things that we’re working on within greek life right now, so it’s definitely a little disheartening to see that some of the bigger issues we’ve faced aren’t included in the Master Plan, in terms of expanding greek housing,” she says. Even with a lack of heavy student involvement, though, these student leaders ultimately believe the Master Plan does a good job of taking students’ needs and wants into account. “The Master Plan is about enhancing quality of student life here on campus,” Voss says. “Even if we didn’t get the kind of voice we wanted, our interests were still represented.” And while the Master Plan is moving forward, it’s not necessarily set in stone — and Capshew says that’s okay. “The Master Plan is a snapshot of the ideas and a plan for the future. It’s not a straitjacket,” he says. “It’s a way to generate ideas and to see, ‘What do we have now? Where do we want to go? What areas do we need to work on?’” This flexibility allows IU to develop as necessary. “Our campus is this living entity that grows and diversifies and changes. It’s a very human place where every area looks natural, and that’s because some people thought a lot about how it looks and feels,” he says. “It’s a very intensely managed landscape and most people often don’t really realize that.” Capshew, who has studied previous master plans at IU that date back to 1885, says campus was originally a mere 20 acres built around Dunn Woods. Through the years, as different presidents with different visions came and went, it grew into something much bigger. “I think the University is very much involved in looking at the path,” he says. “It also has the ability to look into the future and say, ‘Let’s see what we want to take into the future from our past and how we can improve the experience of being a member of this academy.’ In this way, the students have been considered.” The result is a thriving campus filled with students and faculty who find time to pause their hectic daily lives long enough to take a few pictures of some of its prettiest spots on a crisp fall day. They’ll post these photos on Facebook in a subtle attempt to brag to some of their unfortunate friends, who made the obvious mistake of going to school somewhere else — what were they thinking? It’s what makes IU, IU. As SmithGroupJJR moves forward, they say they know there’s no need to trade in the iconic limestone for sleek space stations. It has become clear that many aspects of campus are just classically IU. “The combination and interplay of the historic core, the character of the architecture, the limestone detailing, the landscape, how the buildings were laid into the landscape, the topography, and the woods all really create a strong sense of place for Bloomington. It creates a really strong identity,” Jukuri says. No matter what changes take place here, Capshew believes this will always be true. So does Operations Manager Perry Maull, who went to IU in the 70s and lived in Briscoe Quad. “I came back after being gone for 26 years to a good Indiana Hoosier community,” Maull says. “It’s more than just piles of limestone. It’s the faculty I studied under, my fellow students and friends that I’m still in contact with after all these years. IU’s more than buildings. It’s concepts. It’s people. I don’t think that’s changed.”