The forgotten queen steps onto the empty stage.

She looks out across the cavernous hall of the IU Auditorium. It’s bigger than she remembered. She sees the rows of seats where her friends cheered for her. She feels the crown tilting on her head, hears the flashbulbs popping in her face, catching her surprise as she made history. She never expected to win.

The stage is so quiet now. She thinks back to the Ebony fashion tour that followed her coronation, the dinner with Dr. King. She thinks about the slurs people hurled at her, writing letters, calling her at the dorm. The way her own yearbook ignored her reign. The man pointing the gun.

So much pride and so much hate, all beginning under these lights.

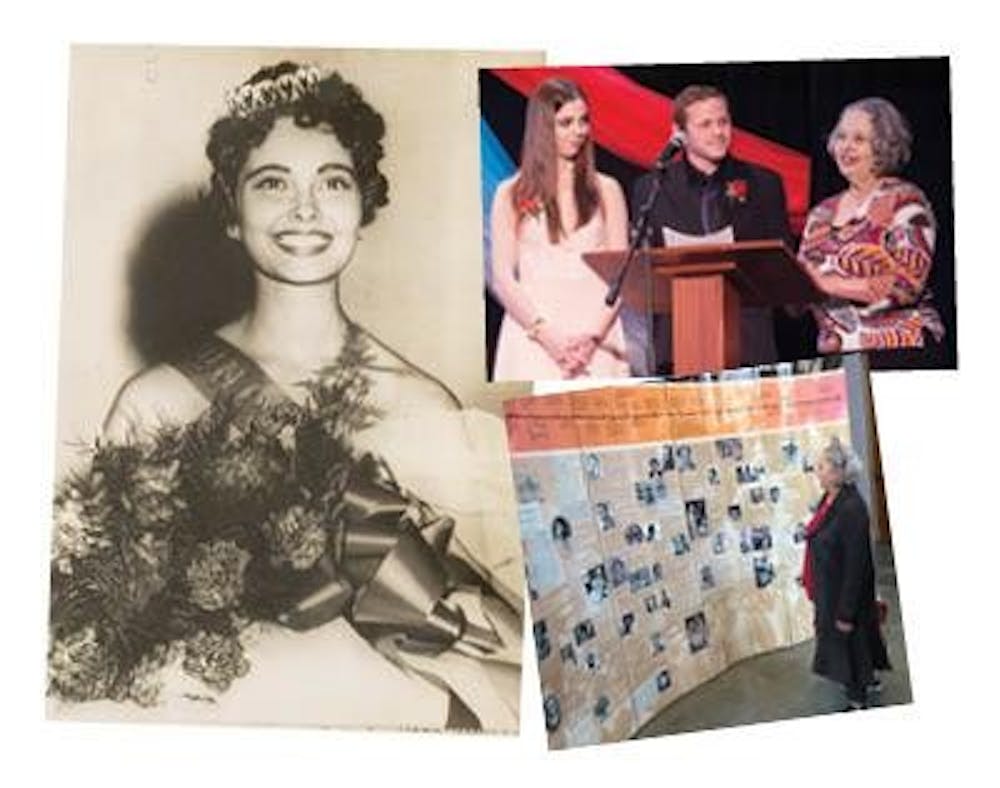

Nancy Streets-Lyons was the first and last black Miss IU, decades before a black woman would be named Miss America.

She is 73 now. Her eyebrows are thinner than they were in the old photos — her hair has turned gray. When she descends a staircase, she takes each step carefully. But there’s still a bob in her walk, and when she smiles, her cheeks break into the same dimples that charmed the pageant judges. She’s not afraid to speak her mind. She’s funny. She’s warm. Whenever she meets someone new, she offers a big hug.

“Oh, please,” she says. “Call me Nancy.”

She grew up in South Bend, where she attended the old Central High School. Her family had traces of not just African-American blood, but Cherokee, Irish and Scottish. Her great-great-great grandmother was Jewish.

One of four children, Nancy was raised in a home that embraced diversity. Her parents were involved with the local NAACP. Her mother was an advocate for the rights of migrant workers and often invited them to join the family at dinner. Her father had gone to IU to be a dentist. Her brothers and cousins studied here, too. When it was time for her to go to college, heading south to Bloomington was an easy decision.

If she had the choice again, she wouldn’t pick IU. After everything she went through, she says, she wouldn’t attend such a large university. Five decades have come and gone since she left this place.

Civil rights legislation was passed and segregation became just a bad memory for generations. Photographs and history books are all that remain of the Little Rock Nine, the Selma and Montgomery marches, Rosa Parks and Malcolm X.

A black man was named president of IU. Another was elected president of the United States.

Nancy was married, had three children and divorced. She worked as a sales representative and for a few years as an English and arithmetic teacher. She fought a rare type of throat cancer. Today she lives in Indianapolis, where she works as an in-home caregiver with Senior Home Companions of Indiana. She fixes meals for and watches over two elderly clients part-time, five days a week.

For years, she didn’t think about the institution that had lifted her up and then knocked her down. Then, last fall, the phone rang. IU wanted its queen to come home.

When Nancy arrived as a freshman in 1957, Bloomington was a community in transition. Because of the liberal leanings of IU and the integration policies of Herman B Wells, the city was more progressive than much of the state. But IU and Bloomington were by no means immune to racism.

Only 30 years before, the Ku Klux Klan had dominated state politics and still had a presence in southern Indiana. Many businesses and restaurants were still operating under the policy of “separate but equal.” Nick’s English Hut only started openly serving black customers the year Nancy started classes.

“Bloomington was not a very nice place to be for black people. How it was that young people went there, they had extreme stamina and patience,” Nancy says today. “You really had to pay attention to what you were doing.”

If you were black, you didn’t go to the east side of the square downtown, she says. Black students sometimes had to travel in groups as a precautionary measure.

The residence halls had been integrated for 10 years, but white students were assigned white roommates, black students were assigned black roommates. When Nancy applied for admission, she sent in a card with her photo and basic information for housing assignments. She had checked the box for “negro,” but someone at IU had just looked at her photo and thought she was white. They assigned her a room with a white girl in the women’s quad, now Goodbody, Morrison, Sycamore and Memorial halls.

Her roommate didn’t care, but Nancy felt uncomfortable. She moved in with her cousin in Smithwood Hall, now Read Center, to “keep the peace.

”While living in Smithwood, she pledged Alpha Kappa Alpha, a historically black sorority. In the spring of her sophomore year, the members of AKA selected Nancy to be their representative in the Miss IU pageant.

“We’re going to enter you because your major is speech and theater,” she remembers them telling her. “Don’t worry about it — we know you won’t win, but we want to be represented.”