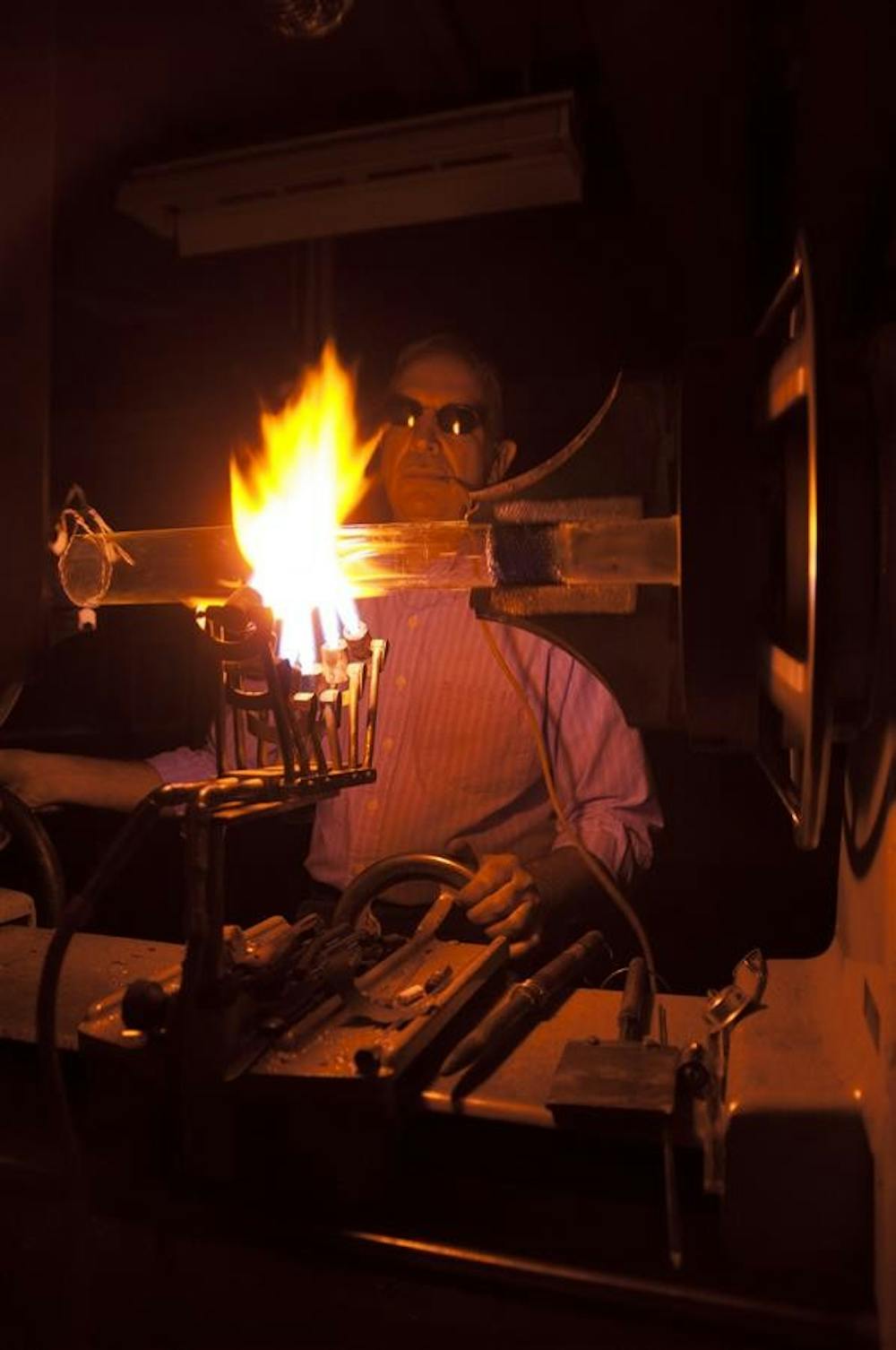

Hidden among the offices and hallways snaking through IU’s Chemistry Building, Don Garvin sat at his bench twirling a glass rod through a flame, the golden reflection dancing across his eyeglasses.

In a matter of minutes, he had turned a hollow glass rod into a swan.

Garvin is the only scientific glassblower serving IU and its satellite campuses. He has spent the last 27 years working with graduate students and researchers in the chemistry, biology, geology and psychology departments.

Garvin’s job is to collaborate with students to create the glassware researchers need to complete their experiments. Students walk in with drawings and discuss their ideas with him, and Garvin creates the finished product.

He estimated he completes between 350 and 500 projects a year. After almost 30 years on the job, he now sees pieces he once created come into the shop to be

updated.

“It’s generational,” Garvin said. “There will be projects that students started back in the ’80s and new students will come in modifying the glassware that we designed. Someone has come up with a better way to make the mousetrap.”

* * *

When he began working for the University in August 1981, Garvin was a stock room assistant in the chemistry store room. Later, he worked as a shipping and receiving clerk.

All of that changed when he met his predecessor, Don Fowler, who approached Garvin and asked him if he would be interested in working as his apprentice.

“I had no idea what that was or anything about it,” Garvin said. “I said ‘Sure, but I don’t know anything about glass,’ and he said ‘That’s a perfect place to be.’”

Garvin spent four years completing his apprenticeship under Fowler, who retired in 1997 after 37 years at IU.

Fowler passed away in July 2012 but left his mark on Garvin.

“Being able to communicate is probably the greatest thing that he taught me and I’d say one of the most important,” Garvin said. “And to have confidence in yourself and yet treat all of the students with the same amount of respect.”

One thing Garvin said he enjoys about the job is that every day presents a different challenge.

“It’s not production work where you’re making the same thing over and over and over,” he said. “It’s different every day, and that’s what I like about it.”

Throughout the years, those daily challenges have changed, Garvin said. Due to higher costs of chemicals, the reactions researchers produce are now getting smaller and so are the chambers.

“The glassware and the designs are smaller,” he said. “Sometimes you’re running out of space to put things in.”

However, his salary and the cost of the glassware is subsidized heavily by the chemistry department, Garvin said, which keeps costs low for students completing research — his lab fee is a mere $5 an hour.

Garvin walked to his desk and picked up a worn copy of a glass catalog, which listed the commercial price of a vacuum manifold, a device that allows a scientist to add or remove gas in a reaction. The catalog price of the manifold is substantially higher than what it would cost him to manufacture the system, Garvin said.

“It would cost about $1,500 to $2,000 to set up a complete vacuum system if they were going to do it commercially, and we could do it for $400 to $500 tops,” he said.

* * *

Though each piece is different, it all starts with an idea.

Depending on the complexity of the piece, Garvin said he can complete a project in a matter of hours or weeks.

Some of Garvin’s pieces were patented. One piece, a spray chamber designed by a student in the 1990s, came to his workshop scrawled on a napkin from a local eatery.

“It goes from the idea to the piece of paper, in this case, which was a napkin,” Garvin said.

From there, he collaborated with the student to turn this idea into a reality.

For Garvin, the opportunity to interact with students in their endeavors has been one highlight of his career.

“You see things evolve, and you see maybe their fourth or fifth year here that they’ve grown, and you’ve grown with them,” he said.

Erick Pasciak, a graduate student studying analytical chemistry, is just one of the many students who has worked with Garvin on glassware projects.

Standing in his lab, Pasciack pointed out dozens of things Garvin had created for his team throughout the years.

“You can’t really look too far without seeing something that Don has made for us,” he said.

Altogether, Pasciak estimated Garvin had created more than 100 pieces of glassware his team uses frequently during its experiments.

Pasciak said he’s friends with Garvin. They chat about everything from Garvin’s family to how he spends his free time. He credits this to Garvin’s relaxed and outgoing

personality.

“I know nothing about fishing, but that man knows so much about it,” Pasciak said. “I love to watch him work.”

Garvin has worked with a wide spectrum of people, from students to researchers at Riley Hospital for Children.

Several years ago he formed a partnership with Dr. Mark Rodefeld, who works at Riley in pediatric cardio-thoracic surgery, operating on the hearts of premature infants.

Garvin worked to design and create a heart pump that would show blood flow and aid in these surgeries.

“These babies are born, and their hearts are so weak,” Garvin said. “Anytime we do anything for Riley, we take a little pride in something like that because we feel that that’s something that’s really going to touch someone’s life.”

Garvin said the unpredictable nature of the material adds to the challenge.

“Everything is a challenge in a different way because you never know what the glass is going to do,” he said. “It’s like a surfer trying to stay on the crest of a wave.”

* * *

In his workshop, hidden deep in what he calls “the bowels of the Chemistry Building,” Garvin waxes poetic about his work and harvesting the potential of glass as a

material.

“It’s one of those materials that is really, really great in the world of science because you can see a reaction going on,” he said. “In glass you can see something happening.”

His fascination for his work carries over to his home life, where he has a bench and workshop of his own and has made Christmas presents or keepsakes for friends and

family.

However, there comes a time for every artist to take his final bow.

Garvin said he would like to train an apprentice of his own to take his place in the shop in the near future.

“In five years, I would see myself perhaps training an apprentice to fill in for my retirement,” he said. “And then I would be at home lifting a glass of iced tea.”

Glassblower crafts science instruments

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe