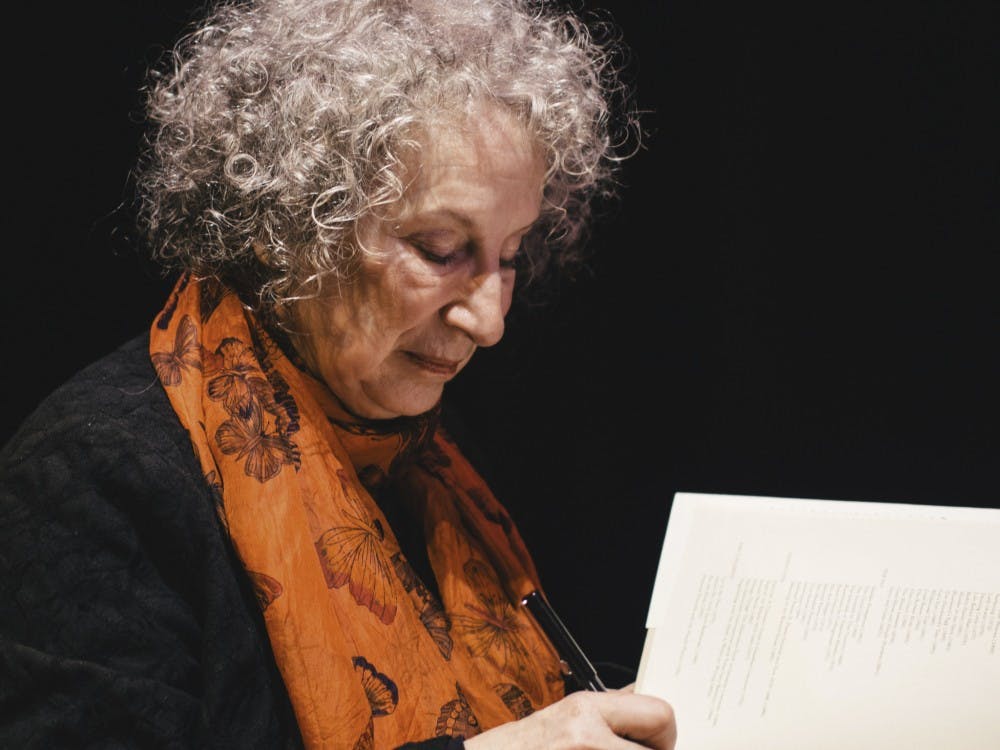

Sipping on coffee and checking her watch, the author looked through papers marked with ?highlighter tucked in a red folder.

Then, Hannah Murray and ?Olivia DeClark, two IU juniors from the English department, stepped up to the podium to ?introduce Atwood.

Murray and DeClark were part of a reading group that has met monthly since September to explore Atwood’s poetry, novels and other writing.

Both students wrote and presented research papers on Atwood at the recent College Arts & Humanities Institute’s symposium discussing Atwood’s work.

They were then selected to introduce Atwood at ?the student-only event Wednesday.

Atwood read selections chosen by IU students and faculty, including a selection from “The Blind Assassin.”

She read about lizard men, luscious peach women and the planets of Aa’A and Xenor.

“If you read any more, my heart would have exploded,” CAHI Interim Director Ed Comentale said after Atwood sat down for the Q&A that followed the reading.

Comentale asked Atwood questions about her life’s work, projects and her writing.

Atwood disputed the “activist” title she is often associated with. She said true activists devote the entirety of their lives to their respective causes.

“I’m a person with no job who contributes her time on a limited basis,” Atwood said. “Really, I am a writer.”

In her book “Oryx and Crake,” there are two institutions, the Watson-Crick Institute and the Martha Graham Academy.

The first is described as a highly rated, well-funded school for STEM, the second as a dilapidated school for the arts and ?humanities.

Though the book reveals a dismal outlook on the future of the liberal arts, Atwood said she does have hope.

Atwood, who has taken an interest in science throughout her career, spoke of how neurologists perceive arts and humanities, physical education, music and interactions with nature as good for child development.

“All the things they tossed out of the curriculum,” Atwood said, chuckling. “They are coming back. Just not fast enough.”

Students also had a chance to ask Atwood questions. Multiple students told Atwood it was an honor to see her speak.

Atwood told the audience she is currently ?working on four different projects, including finishing a novel due out in the fall and contributing to “The Future Library,” a project in which one writer per year contributes a text for 100 years, continuing until the project is finished in 2114.

Eventually these texts will become an anthology of books printed with paper supplied by a forest planted in Norway.

Questions ranged from how Atwood finds the time to write so much and whether she tailors her writing to fit her ?readership.

Speaking to writers, Atwood said repeatedly, “Your duty is to the book.”

Atwood urged writers to focus on being honest in their writing rather than focusing on how readers will respond.

She said, however, that a writer is always writing for someone.

“If you were just writing for yourself, you would just write it and burn it,” Atwood said. “You are always writing to somebody.”

Atwood also encouraged readers to read works they do not expect to enjoy. Atwood spoke of how she has a varied readership. She receives mail from people of all ages from across the globe.

“I would say to you, as readers, to pick something that makes you really uncomfortable,” she said.

Yet for people like English professor Monique Morgan, it is Atwood’s ability to address serious issues that makes her work so valuable.

“She keeps up with the latest developments in science,” Morgan said. “She cares deeply about political movements. I think she’s a wonderful representative of how literature can speak to so many different constituencies and bring them in conversation with each other.”