She grew up in Taiwan but lived in Texas from ages 5 to 7, a formative period for language and emotion. As her inner world was expanding, she learned to describe it in English. That gave her a vocabulary and a skill that she uses now to help other Asian ?students.

In February, Lei and others started a Mandarin language counseling program at the Center for Human Growth in the School of Education.

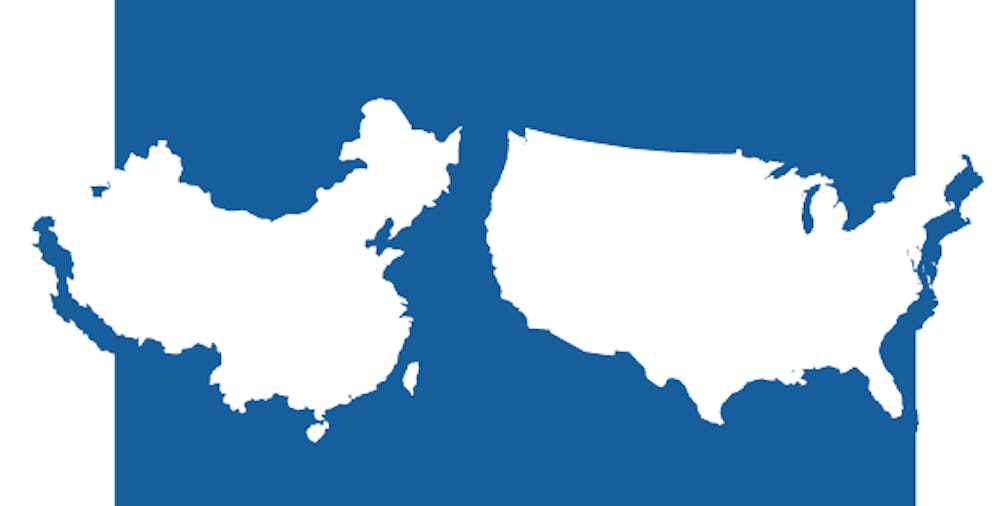

Between counseling, classes, volunteering at the Asian Culture Center and socializing with the Taiwanese community in Bloomington, Lei navigates two languages in three different contexts — speaking, thinking and feeling. Many Mandarin speakers who come to the United States — the majority of IU’s international student population — must bridge those worlds.

Mandarin lacks an emotional vocabulary, Lei said. There is a word for “sadness,” but no words to explain intensity, such as “desolate,” “gloomy” or “downtrodden.” How, then, does an English-trained counselor, equipped with hundreds of nuanced emotional words, try to help a young ?Mandarin speaker?

Most students who need counseling start at Counseling and Psychological Services, but CAPS does not yet have counselors who speak ?Mandarin.

“The communication involved in an upper respiratory infection is much different than one where you are managing depression,” Executive Director of IU Health Center Pete Grogg said. “There are different nuances and the communication, you just can’t get through translation. You really need somebody who can speak the language and be able to assess the person’s body language, a lot of ?unspoken communication.”

That’s where the Center for Human Growth and OASIS International come in.

The new program seeks to connect with international students and help them acclimate to life at IU, said Lynn Gilman, director of the CHG. Alongside the newly created Mandarin program, the CHG has also sponsored a Spanish program since 2013.

The Mandarin counseling program began as a social support group that brought Mandarin speakers together to talk about adjusting to American life.

“When international students first arrive, they of course have an orientation, but a lot of that involves documentation and other issues of immigration that are really technical,” Lei said.

But what about trying to fit in with Americans who speak differently, eat differently, learn differently? What about learning to critically think in the classroom when your tradition back home is that teachers should be highly respected and therefore are all-knowing? What about rejecting unwanted sexual advances or offers of alcohol, even though you want to belong?

Counselors in the U.S. are taught in a Western context with a culture that values emotional expression and a language that enables it. Reaching students outside that context requires knocking down more than one wall — stigma included.

For instance, insisting that a person from a collective, group-oriented culture become more independent from their parents may not be appropriate, Gilman said.

Shu-Yi Wang (not related to Lei), another doctoral student from Taiwan and a counselor in the CHG, worried at first that principles he learned during his English counseling training would not easily apply to his clients.

Or, perhaps he’d lack the vocabulary in Mandarin to do it properly. Would Mandarin clients feel alienated by all the emoting?

In many Asian cultures, it’s common to keep feelings bottled up and hope they go away, Lei said.

During counseling sessions, Mandarin speakers often describe physical symptoms such as stomach cramps as a consequence of emotional distress, rather than opting to try to explain their mental state. Counselors may help Mandarin speakers search for a metaphor or ask specifically, “What does this emotion mean to you?”

Yi consciously slows down his pace and asks questions to discern the level of ?acculturation — how ingrained the client is in American culture. He asks whether the client prefers to speak in Mandarin or English. They usually choose Mandarin.

“The key is to make it feel more low risk so that those who need more help will consider other services,” said Ellen Vaughan, assistant professor in the counseling and education psychology program.

Only a small percentage of students access counseling services at all, Vaughan added. Stigma about attending counseling for issues besides psychosis is strong.

“Self-reliant cultures often stigmatize it more,” Yi said. “Emotive cultures like America don’t as much.”

Male clients, afraid of looking weak, may feel particularly wary of speaking to female counselors.

To Lei, Yi, and the other counselors at the CHG, spreading the word and providing language counseling services is a social justice issue — a way to break barriers between people and end the marginalization of others.

“Since we have the capability to do it, it’s the right thing to do,” Gilman said.

Megan Jula ?contributed reporting.