In his hands, he cradles a mold of an orangutan skull. The species he worked with every day at the zoo, the species he dreamed about as a child, is disappearing.

Dr. Robert Shumaker remembers the trip to Borneo. There were more than 200 baby orangutans crammed into cages by the dozen. Watching the doctor with their brown eyes, their long fingers clung to the metal bars. As he stepped between the cages, he realized he was looking at what could be the last generation of orangutans on Earth.

He brushed his finger against their tiny hands.

***

That was 15 years ago.

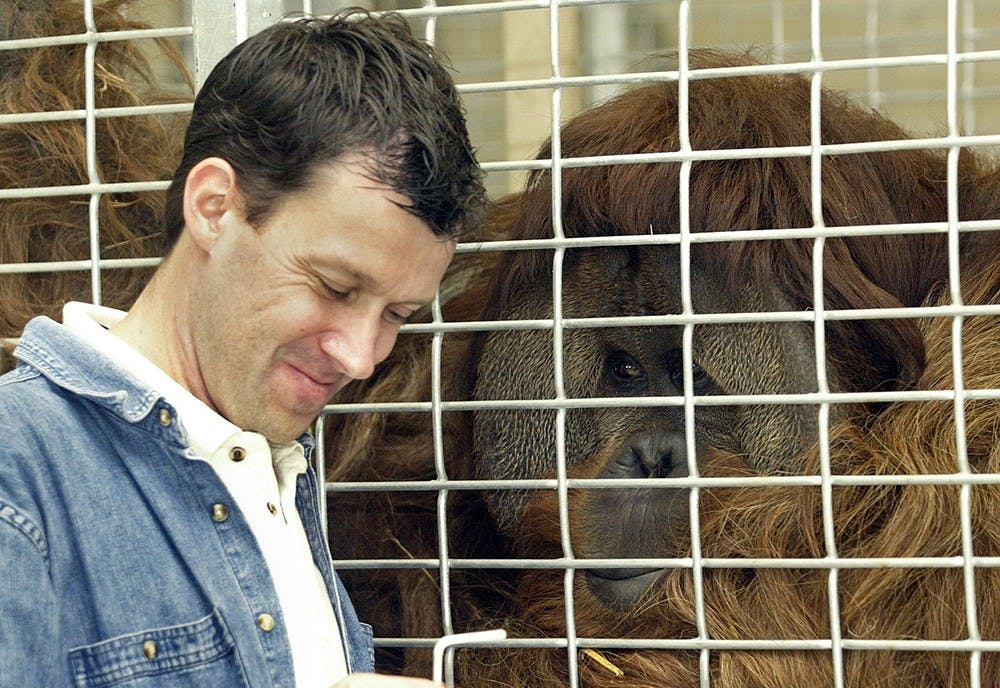

Now, through a thin opening in the exhibit window at the Indianapolis Zoo, another orangutan reaches toward him. This one has never seen a rainforest, never climbed a tree outside of the United States.

Dr. Rob— almost everyone calls him Dr. Rob — places a paper cup full of banana chunks in the open palm. The orangutan tilts the cup into his mouth.

“All right, Azy. Ready?”

When he walks around the zoo, he carries himself with a sense of focused urgency.

At 51, Dr. Rob is known for his research on the cognitive abilities of orangutans.

He’s more than 6 feet tall and wears plaid shirts tucked into khakis. He never calls his demonstrations shows. People think less of apes, he believes, when they’re made into a spectacle.

Dr. Rob has worked with Azy for more than 30 years. He calls Azy his colleague and his friend. Through his daily demonstrations, he pins his hopes for the future against the threat of extinction by showing people how similar we are to orangutans.

The 250-pound orangutan slouches against the wall of glass. Behind him, fire hoses dangle like vines above the concrete floor. His orange-brown fur is thick and long, covering his back and legs, with ?matted tassels hanging from his arms. Wide cheek pads frame his dark brown eyes, which scan the room of people.

Dr. Rob turns to Azy while attaching a body mic to his collar.

“Check, check.”

He looks out at the crowd.

“Let’s get started.”

***

His most vivid childhood memory is standing in his sneakers, lunchbox in hand, watching an orangutan at the National Zoo. He was only 5 years old, but he still remembers the large, round face and the small, intense eyes staring back. He saw a humanness there. He wondered what the orangutan was thinking.

Ever since that day, he’s wanted to work in a zoo.

Dr. Rob first met Azy in 1981, as a high school volunteer in the National Zoo’s Ape House. He made sure the animals were safe and the exhibit was clean. Whenever he got the chance, he held informational classes for zoo visitors.

Azy was already a juvenile. His ?impressive cheek pads hadn’t formed yet. Rambunctious and ?mischievous, he always wanted to play and wrestle with the ?other apes.

Dr. Rob never imagined how they would grow up together, how his fascination with Azy would turn into his life’s work.

In 1992, as part of his graduate studies, Rob helped design an exhibit called the Think Tank. The exhibit tested the cognitive and tool-making abilities of the zoo’s orangutans. At the Think Tank, the apes learned to combine biscuits with water to make gruel and to use rods to reach grapes from long distances. Dr. Rob used flash cards and computer monitors to teach orangutans to associate abstract symbols with things and people — a rudimentary language, just for them.

Eventually, Dr. Rob opened the demonstrations to the public. He would ask Azy to look at a picture of an object and select the correct symbol for it, right in front of a crowd. Azy and the other orangutans learned the symbols for apple, banana, Dr. Rob and Azy. Dr. Rob noticed how Azy’s younger sister Indah always picked up numbers faster than he did.

It was around then when Dr. Rob met Anne, a student volunteer who helped narrate the elephant demonstrations. Anne started making excuses to help out at the Ape House. In her mind, Rob was a different class of keeper. He stopped carrying a wallet, because the orangutans kept fishing it out. He even made sure the zookeepers surprised the apes with cakes on their birthdays.

Anne always joked Indah was the “other woman” in Rob’s life. She knew Indah was in love with him when she saw her looking at Rob with her hands clasped together, head tilted to the side like a hopeful romantic.

“All dreamy-eyed,” Anne said.

As the Think Tank’s popularity grew, Azy and Indah became something of celebrities. Their names were in the paper. Indah’s face was on the cover of Smithsonian ?magazine.

In 2000, Dr. Rob and Anne got married. On his bookshelf, he put a picture of Anne from their wedding day next to a vintage Dr. Zaius action figure from “Planet of the Apes.”

After almost two decades at the National Zoo, Dr. Rob moved to Des Moines, Iowa, where he joined the Great Ape Trust. With the support of the National Zoo’s primate curator, Dr. Rob brought Azy and Indah with him.

But within six weeks of moving to Iowa, Indah developed an intestinal ?infection.

One night, Azy watched as Dr. Rob and staff carried an unconscious Indah from the exhibit.

Even with the emergency surgery, Dr. Rob knew it was too late.

“When we lost her, we lost 50 percent of ?everything,” he said.

She was 24.

Dr. Rob knew he and Azy were grieving together. After Indah’s death, Azy sought out the company of others almost constantly. First thing each morning, he waited for Dr. Rob and the other keepers near the entrance of the exhibit.

They sat near each other without speaking. Through mesh netting, they worked on Dr. Rob’s research or held hands. But mostly, they sat together on the floor of Azy’s living area and stared. All Azy wanted was his ?company.

Dr. Rob couldn’t be sure Azy understood that Indah died.

“But he certainly understood that she was gone,” ?he said.

In 2009, Dr. Rob moved to Indianapolis to help open the Simon Skjodt International Orangutan Center. Dr. Rob’s role as the vice president of conservation and life sciences put him in charge of the zoo’s many animal and conservation departments, but his primary research remains with the orangutans.

Dr. Rob and conservationists at the Indianapolis Zoo set out to make Indianapolis the most ?orangutan-literate community in the world.

***

After arriving in Indianapolis, he hung a photo on the wall next to his new desk — Indah’s hand and his own, clasped together, tight.

All Dr. Rob wants is to make people care more about orangutans as complex creatures that deserve our respect.

Especially in a world that’s working against them.

Development of palm oil plantations in the Southeast Asian islands of Borneo and Sumatra is destroying the wild orangutan’s habitat. Dr. Rob remembers the machines cutting through the rainforest like weed whackers, the severed tree trunks clogging the rivers. He knows if nobody does anything, orangutans will die out in 10 to 20 years.

On his trip to Borneo in 2000, Dr. Rob watched local women at the rehabilitation center carry the babies from cage to cage. They fed them, they held them. When the orangutans matured, the center’s staff tried releasing them back into the wild. It worked for a few, but many orangutans needed to be taught to climb trees. Those that could be released trusted humans and became easy targets for hunters and farmers. For every baby he saw in the center, Dr. Rob guessed at least a mother and three other ?babies had died.

Loggers and palm oil plantation owners have destroyed more than half of the orangutan’s natural environment in the past two decades.

He looked at the infants and thought of the orangutans in zoos back home. They ?were safe.

After opening in May 2014, the Indianapolis Zoo’s Orangutan Center became the largest of its kind. Architects designed it to give the orangutans choices within the exhibit. Hidden passageways connect the atrium to outdoor yards and the Hutan Trail, an aerial rope line 85 feet above the ground without a net.

As visitors walk through the exhibit, a few swipe their credit cards at conservation stations that allow them to symbolically plant a tree in Borneo. Dr. Rob helped start a tree-planting project in conjunction with the Kutai National Park. The zoo spent more than $10,000 to restore orangutan habitats, which would plant more than 1,000 trees. More trees mean more homes for the orangutans.

Some have labeled the plight of orangutans the worst conservation failure of our time. During the past decade, conservationists have increasingly looked to zoos and to people like Dr. Rob to rescue the species from extinction.

***

Azy presses the touch screen.

“He’s very confident,” Dr. Rob says to the audience during his demonstration. “He can use photographs and drawings to identify objects.” In today’s case, he tests Azy’s ability to recognize and tap a symbol for the word “cup.”

He presses the space bar on his laptop. A dozen symbols flash onto Azy’s touch screen panel, his eyes darting between each one. Some are squares. Some are lines or squiggles, all a part of the symbolic language Dr. Rob developed. Azy taps a circle with a dot in the center.

“Good, good, good!”

Another set of symbols appear on Azy’s screen. He motions toward the circle with a dot in the middle, but hits the wrong one.

Buzz.

No treat.

Azy tries again, but the same thing happens.

“Hold on, hold on,” Dr. Rob says, as Azy tries another time. “His hair is in the way. Give me your hand, Azy.”

The audience chuckles.

Dr. Rob grabs Azy’s palm and brushes his soft hair away from his fingers.

Orangutan hands feel like human hands. Some are rougher, some are smoother. Every orangutan has a unique fingerprint. They don’t like to be dirty or touched by strangers. They let only their friends touch them.

“We’ll have to trim that later,” Dr. Rob says, letting go.

Orangutan fingers are twice as long as a human’s. Just one of their fingers can support the entire weight of their bodies. Male orangutan arms stretch nine feet from fingertip to fingertip, which is why wild orangutans hardly touch the ground. They’re climbers.

“Good progress today,” Dr. Rob says. “Alright, bud.”

It’s a busy Wednesday afternoon, and children are in awe of Azy as he recognizes symbol after symbol.

They sit on the floor while conservationist Paul Grayson stands nearby.

“We want people to understand that the loss of orangutans would be like losing one of our closest friends,” said Grayson, the zoo’s senior vice president of conservation and science.

Grayson’s phone rings.

“Hello?”

His wife is on the other end. She is bringing their grandsons to the exhibit.

“Great,” he says. “I’ll be here.”

Grayson tucks his phone in his pocket as more school groups watch the ?presentation.

Some of the children yell, “Azy!”

Huh, Grayson thinks to himself. They remembered his name.

***

Dr. Rob closes his laptop as the audience disperses. The school groups go on to the next exhibit, to the elephants or the dolphins. Three screens above Azy play footage of wild orangutans swinging from branch to branch. The rainforest looks lush and peaceful.

Dr. Rob wonders if it will work. Will the exhibit make people care? Will he see the extinction of orangutans, even after all he’s done?

Sometimes he can’t help but bring his work home ?with him. He always has a thing against apes in show business.

One time Anne bought a VHS tape of “George of the Jungle" from a garage sale.

“No child of mine will watch this,” he said, opening the lid of a trashcan. He broke the tape in two and threw it away.

Anne and Dr. Rob have two children: Carly, 9, and William, 13.

Dr. Rob fears his two children will grow up to a world without orangutans. He knows if conservation efforts don’t improve, wild orangutans will die out within ?Carly’s and William’s lifetimes.

Azy is 37, with a life expectancy of about another 15 years. Dr. Rob is about the same distance from retirement. In those next 15 years, Dr. Rob believes, the future of the orangutans will be ?decided.

Azy scoots away from the window.

Dr. Rob unclips his body mic.

He doesn’t know anyone who has worked with one orangutan for 30 years, or even 20.

“It’s not something you can really talk about with other people.”

As far as he knows, their friendship is the first of its kind.

He has to believe it won’t be the last.