Cristian Medina wanted to show the world his house.

Or rather, he wanted to show the world his house of cardboard books. Medina, a geologist at the Indiana Geological Survey, co-founded Cardboard House Press, a publishing house dedicated to creating poetry books from recycled materials.

He quoted German poet Bertolt Brecht: “I resemble the one who carried around with him the brick to show the world what his house was like.”

Instead of bricks, he prefers cardboard to build his house of books.

The idea behind Cardboard House Press is to promote Latin American and Spanish literature by making it available to both Spanish and English readers in Bloomington.

“We want to engage the community,” Medina said. “Our motivation was to disseminate and to publish Latin American and Spanish poets.”

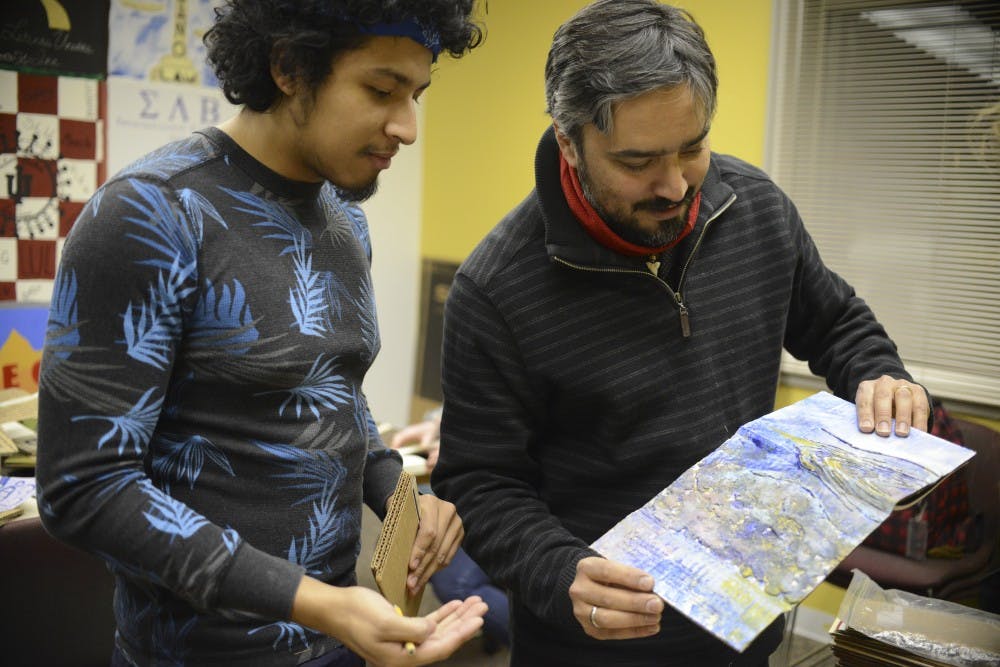

These art-books, as they are so-named, are created from recycled cardboard dug from recycling bins, marbled paper, stenciling and hand-sewn binding.

All of the books created are bilingual with the Spanish version of a poem on the left page and English on the right. Volunteers assemble the art-books entirely by hand in weekly workshops at the La Casa Latino Cultural Center. The final product can be found on the shelves at Boxcar Books for sale.

“This is a way of bringing the poetry that I’ve read from South America that is so rich, so diverse and vast and to show it to people who otherwise wouldn’t have the opportunity to do that,” Medina said.

The idea behind Cardboard House Press originated from Cartonera, a publishing movement that began in Argentina in 2003. After an economic crisis in 2001, there was an increase in cartoneros, people who make a living from collecting and selling recovered materials to recycling plants.

Cartonera books are made from recycled cardboard purchased from the cartoneros at higher prices than what would normally be offered by recycling plants. The cardboard covers were painted by hand, and the books were sold in the streets in order to increase access to works of literature otherwise unknown to the public.

Since then, the movement has extended throughout South America and has even crossed oceans, touching Europe and the United States.

“The idea was to promote and distribute and make books that everyone can have for low prices,” Medina said.

He, along with Paul Guillén, Maggie Messerschmidt and Giancarlo Huapaya, came up with an idea to start their own project embodying this Cartonera movement in Bloomington. In 2014, they began a small workshop for children at the Monroe County Public Library.

In this seven-week series, children were grasping paintbrushes and pens, painting their own art and writing their own poetry. The workshop concluded with a poetry reading and an exhibition of the children’s work at the Showers Building in downtown Bloomington.

“At the time, we were not sure if we were going to continue with that, but we had so much approval and encouragement from people saying, ‘This is fantastic,’” he said. “So we decided to follow up with that and turn this idea into a more serious, if you will, project.”

And from that project, Cardboard House Press was created.

The publishing house adopted its name from Peruvian writer Martín Adán’s book, “La Casa de Cartón,” or “The Cardboard House.”

Every book they stitch together is unique, Medina said.

Behind each book, there is an artist who paints the inside covers, a translator who reworks the poems into English, an editor who oversees the translations and a volunteer who puts it all together.

But Medina said he and fellow editors must be meticulous when it comes to these translations and make sure the text represents the original poem accurately.

“When someone translates a poem we believe that you are somehow creating a new poem,” he said. “There will be as many translations as translators.”

While the number of volunteers at Cardboard House varies per semester, it maintains a core group of “regulars” who participate every week.

Lilian Burgos, who works at the IU Physical Plant, did not think there was a Spanish community in Bloomington until she discovered a notice about the workshops in an email from La Casa.

“I came and decided to see what it was all about,” she said.

Now, Burgos said she loves spending time working with fellow volunteers to create the art-books.

IU sophomore Brandon Diego, a computer science major, attended the group’s first poetry reading. He said he enjoys the workshops and likes working with his hands.

The beauty of it all, Medina said, is that the volunteers become part of a larger community, forging friendships through literature, culture and cardboard.

And together, they intertwine Latin American and Spanish poetry with art by creating these cardboard books and sharing them with Spanish and English speakers alike.

“Between languages and cultures, there shouldn’t be boundaries,” he said. “And that is one of the premises we use. We bring cultures and art together by providing translations.”