Whenever somebody famous dies, there’s almost always a cultural re-discovery of their work as the living shamble en masse to consume whatever art they created. It’s a collective grieving process as much as it is a way to memorialize the departed and prove to ourselves that art can transcend death.

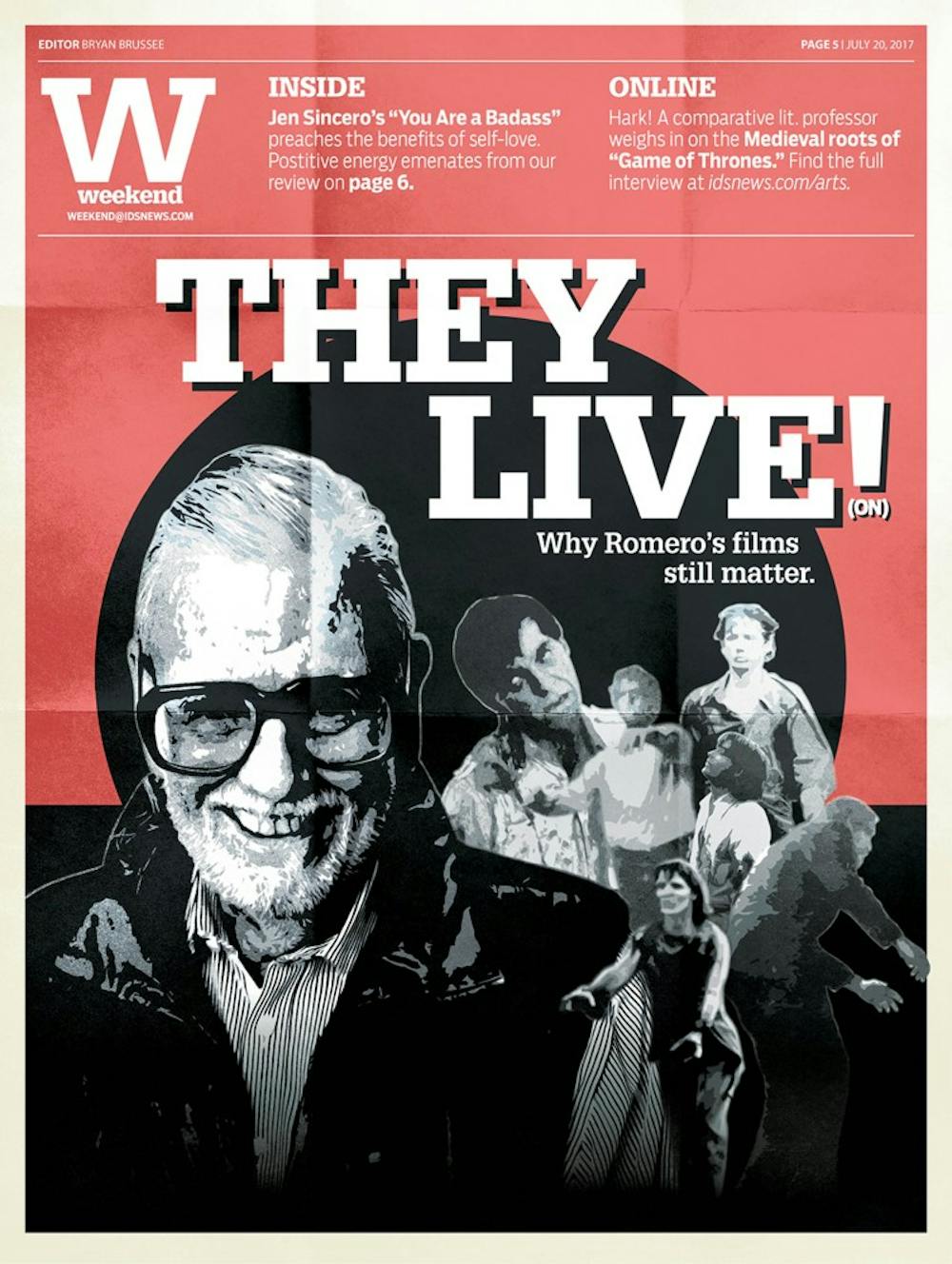

George A. Romero, father of the modern zombie movie, died Sunday, July 16, in Toronto. His death followed “a brief but aggressive battle with lung cancer,” his family said in a statement. He was 77.

In the hours and days following his passing, what we’ve seen hasn’t been so much a re-discovery of his films, which include 1968’s “Night of the Living Dead” and 1978’s “Dawn of the Dead,” but the continuation of an ongoing cultural fascination with zombies.

With shows like AMC’s “The Walking Dead” and blockbusters like 2013’s “World War Z” dominating TV and film today, we’re only now starting to see the pay-off of Romero’s work. Even though he practically invented anatomically-correct gore, the most vital bits of Romero’s films have always been their brainy and ever-mutating subtext. His films helped the zombie movie shamble beyond the drive-in circuit because his take on the undead —slow-moving, brain-dead and all-consuming — is an endlessly rich allegory for American life.

The US was three years into the Vietnam War when Romero shot his black and white debut outside of Pittsburgh on a budget of $114,000. One of the first dominant visuals following the opening credits of “Night of the Living Dead” is an American flag waving in the graveyard as the siblings Barbara and Johnny Blair pass through to lay flowers at their father’s grave. America and its body count was on Romero’s mind, and his zombies — the first of which stumbles along as the Blairs are heading back to their car — look a lot like us.

“I took them out of ‘exotica’ and made them neighbors,” Romero told NPR of his approach to the monster in 2014.

It was also a time of domestic unrest, with race riots raging in cities across the country. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis while Romero was driving across the East coast with a copy of the film in his trunk, searching for a distributor to hand-deliver it to. At the film’s conclusion, Ben — played by Duane Jones — a survivor and one of the first black men in a starring role that wasn’t specifically written for a black man, is killed by a white deputy mistaking him for a zombie

It was an era of arbitrary and senseless violence, and the boogey-men responsible were neighbors and politicians. In some ways the world was a different place in 1968, and in other ways it wasn’t that much different from today.

Romero’s next film, “Dawn of the Dead” would go on to critique capitalism. The zombies of the first film, generally dressed in funeral clothes and presumably fresh-out of the grave, were replaced by “everyman” zombies clad in street clothes and drawn even in death to the places that mattered most to them in life: in this case, a shopping mall. Much as mindless violence dealt the final death blow in “Night of the Living Dead”, it’s the infighting among the mall’s survivors after they’ve already run the zombies out that’s their ultimate undoing. Roger Ebert, who’d been disturbed by the first film’s violence, called its sequel “one of the best horror films ever made” in his Chicago-Sun Times review.

The rest of Romero’s films, released about once every 10 years, would use their undead hordes to critique other aspects of American life. 1985’s “Day of the Dead” was a scathing indictment of Cold War militarism, and Romero’s 2000s trilogy added a modern twist to the themes explored in his previous work. Romero’s last “Living Dead” project was the 2014 Marvel comic book series “Empire of the Dead,” which introduced vampiric politicians. Even though he’d been discouraged by Hollywood’s increasing reluctance to finance his small budget zombie films, Romero never lost his black sense of humor.

In his Hollwyood absence, a new breed of director rose up to re-invent the genre for different times. Danny Boyle's 2002 film “28 Days Later” fed on anxieties over biological warfare and the SARS outbreak in China earlier that year. AMC’s “The Walking Dead,” an adaptation of Robert Kirkman’s ongoing series of comic books, uses its characters to examine our fundamentally violent Id and broadcasts the results to 18.8 million views with each episode, as it did on average in 2016 according to Nielsen.

Sometimes it feels like zombies are so popular that if an outbreak actually happened, we’d all be pretty well-prepared with the requisite chainsaws, sawed-off shotguns and crowbars. Which begs the question: with zombies more popular than they’ve ever been, what do they mean to us now?

There’s an answer that think pieces and YouTube blogs point to over and over again, and it goes like this: Zombies lack high-functioning consciousness, and they mindlessly follow the horde. They don’t so much think as react to whatever is in front of them, and they move slowly and clumsily. If you’ve ever found yourself bumping into something while walking and looking at your smart phone, you see where I’m going with this. Mike Rugnetta, who runs YouTube’s PBS Idea Channel, makes the argument that zombies might represent a fear of losing ourselves completely to technology, and he’s just one of many in the hive-mind.

There’s an interesting flipside to that argument, though; the survivors of a zombie apocalypse could also represent us in the wake of massive technological upheaval. Chuck Klosterman, writing for the New York Times, makes the argument that getting through daily life not is unlike struggling to survive a zombie apocalypse.

“Battling zombies is like battling anything ... or everything,” he writes, and while that’s a bit vague, it also makes complete sense. Sometimes working a job can feel like conquering a never-ending onslaught of individually manageable but collectively insurmountable tasks; surviving a zombie apocalypse mostly involves killing one slow-moving, easily bludgeoned zombie in an otherwise unstoppable horde after the other. In both cases, it’s the bigger picture that’s overwhelming and the individual tasks that are mind numbing.

Released in 2004, this is what Edgar Wright’s “Shaun of the Dead” understands. One of the few new zombie movies that Romero enjoyed, it mixes legitimate gut-spilling horror with droll comedy to explore how actual people familiar with zombies would react. We’d try to find to our loved ones, and we’d probably do anything to survive, even if that meant slinging slabs of Prince vinyl at backyard zombies. It pre-dated the era of smart phones, but it paints a picture of the zombie apocalypse that's still completely relatable. "Shaun's" zombies are scary, but also not completely unmanageable. At times killing them is just a chore. They represent modernity.

Or maybe that's overthinking it. Maybe without the clear symbolism Romero animated them with, zombies, in all their corpse-y glory, might just represent our oldest fear: death — that elemental force that shambles slowly but surely after everyone. We’ve lost a profound talent in George Romero. But his vision lives.