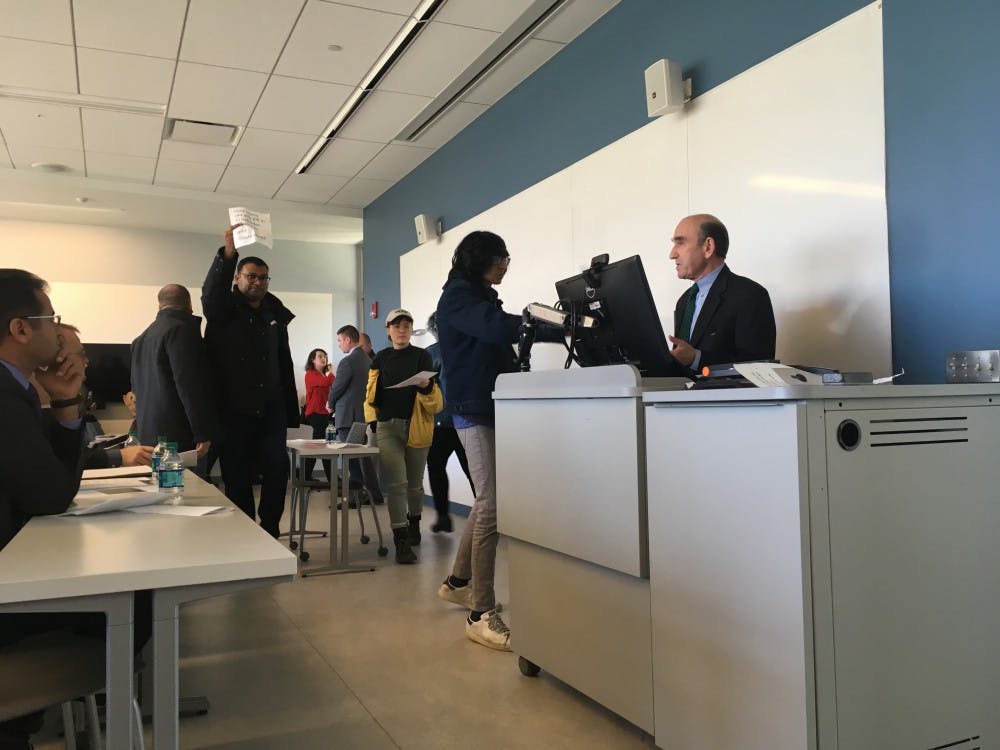

When a former assistant secretary of state stepped to the lectern in the Global and International Studies Building on Friday afternoon, the room was full. Then, Elliott Abrams started speaking, and within four minutes, most of the audience left in protest.

Abrams came to campus to discuss democracy promotion in the Arab world as part of the Tocqueville Lecture Series, a program through the Ostrom Workshop which has invited speakers such as Charles Murray. The program was not sponsored by the School of Public and Environmental Policy or the School of Global and International Studies.

Those who protested the discussion Friday said they did so because of what Abrams did when he served in government, not because they disagreed with his ideas.

“It’s not a crime to hold any thoughts in this country,” Associate Professor Abdulkader Sinno said in an interview after the discussion. “You can think whatever you want — that’s your freedom of thought. But if you hurt other people, you’re a criminal.”

Abrams, a senior fellow for Middle Eastern Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, served in the Reagan Administration in the 1980s and pleaded guilty to two counts of withholding information from Congress during the investigation into the Iran-Contra scandal.

Sinno, one of the vocal opponents of Abrams’ appearance on campus, said he appreciated the way IU administration handled this event as opposed to Murray's appearance last spring. In a follow-up email, Sinno said professors at IU teach students to behave ethically in any profession they plan to enter, and wondered what sort of message was being sent to students when someone who broke the law was invited to speak.

The independent counsel appointed to investigate officials implicated in the Iran-Contra scandal prepared a multi-count felony indictment against Abrams but ended up proposing a deal in exchange for his cooperation, according to the summary of the investigation.

He was pardoned by former president George H. W. Bush and served on the former president George W. Bush’s National Security Council in the early 2000s.

The protest Friday was not focused on the scandal Abrams was officially implicated in — soliciting funding for rebels in Nicaragua. Demonstrators held up signs calling him complicit in the deaths of thousands in other Central American countries like Guatemala and El Salvador.

When the audience members left, they placed their signs on the lectern in front of Abrams, who did not appear to respond. Other demonstrators taped similar fliers on the back window of GISB 1100, where the discussion took place.

The discussion focused on democracy in Arab countries. After Abrams delivered his initial remarks, Assistant Professor Asaad Alsaleh issued a rebuttal.

Abrams took a more interventionist position, and Alsaleh said people in these countries who are skeptical of United States interference remember how the U.S. labeled past interventions.

Abrams said mediation could be provided by private entities as opposed to specific countries intruding on the countries’ governmental processes.

“I don’t suggest the U.S. government does it directly, but through private human rights organizations,” Abrams said.

Olivia Little, a junior studying law and public policy, said she and her fellow demonstrators were trying to bring attention to what they said was Abrams’ complicity in genocides in Guatemala and El Salvador.

“There’s no reason to give him respect or a platform,” Little said.

Abrams was not available for an interview, and his point of contact at CFR directed questions to Leslie Lenkowsky, a professor emeritus in SPEA who in turn pointed to the director of the Tocqueville Lecture Series, who did not immediately return a phone call seeking comment.