It’s difficult to pin down exactly where Kanye West lost his way. From 2004’s “The College Dropout” to 2010’s “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy,” his path has been constantly evolving.

The former solidified his presence at the table of established artists, and the latter forced people to examine not just Kanye West the artist, but Kanye West the individual.

However, “Ye,” West’s seven-song album, released May 31 via a livestream party in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, makes one thing abundantly clear about the path West finds himself on: he’s lost.

Longtime fans will notice West borrowing sounds and samples from nearly every previous album he’s produced, though now with more maturity.

Gutted, distorted guitars mixed with auto-tuned vocals that shimmer alongside sparkling choirs – like those heard on “The Life of Pablo” – and remixed samples, like those that made appearances throughout “The College Dropout,” are all present.

Releasing an album in the middle of a mountain range emphasizes the absurdity of the album. Its inconsistencies lead to a blurry and barren listening experience.

The bright, electric orange of “The Life of Pablo” has given way to a broader, grayer color palette. While West has established an affinity for creating moods within his album, the mood here is that of a rapper trapped between his empty, upscale mansion in the sun-soaked hills of a conceited, vapid reality, and his own mind.

The album is a mere 23 minutes long. This means West spends 23 minutes flip-flopping narratives without finding any solid ground to stand on.

The first track on the album, "I Thought About Killing You," addresses his internal struggle to combat depression, anxiety and life in the public eye. Other tracks, such as “Wouldn’t Leave” examine the survival of his marriage to Kim Kardashian, a marriage that hinges on the sanctity of their conjoined brand.

“Violent Crimes,” a song which finally examines his role as a father, retains a sweet message at its core, but ultimately falls short of tugging on anyone’s heartstrings besides his own. It contradicts nearly every song before it in which he talks about infidelity and objectifies women.

What West has done with this album is solidify what everyone has been thinking for a while.

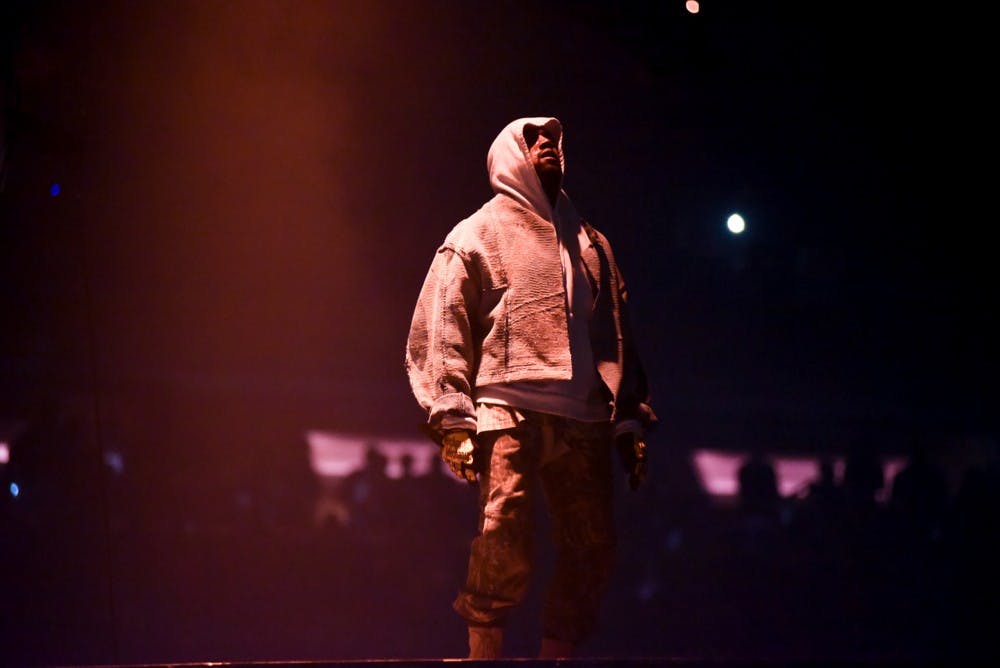

His sharp, creative edge now feels more like a dull butter knife. He is no longer the intense creator, pacing back and forth deciding whether a choir or string section would better complete a track. Instead, we’re left with an uninspiring, seven-track album made by an artist who is talking to himself.

The fact anyone is listening to the album is collateral damage. That is where the true pitfall of this album lies.

He used to make music that challenged the audience. Now he creates albums, like this one, for an audience of one — himself. By the end of the album, he’s left pleading with himself.

The genius of his previous albums has all but eroded, and what’s left is West, alone at center stage, begging for people to hear him. It’s just too bad he won’t listen to himself.