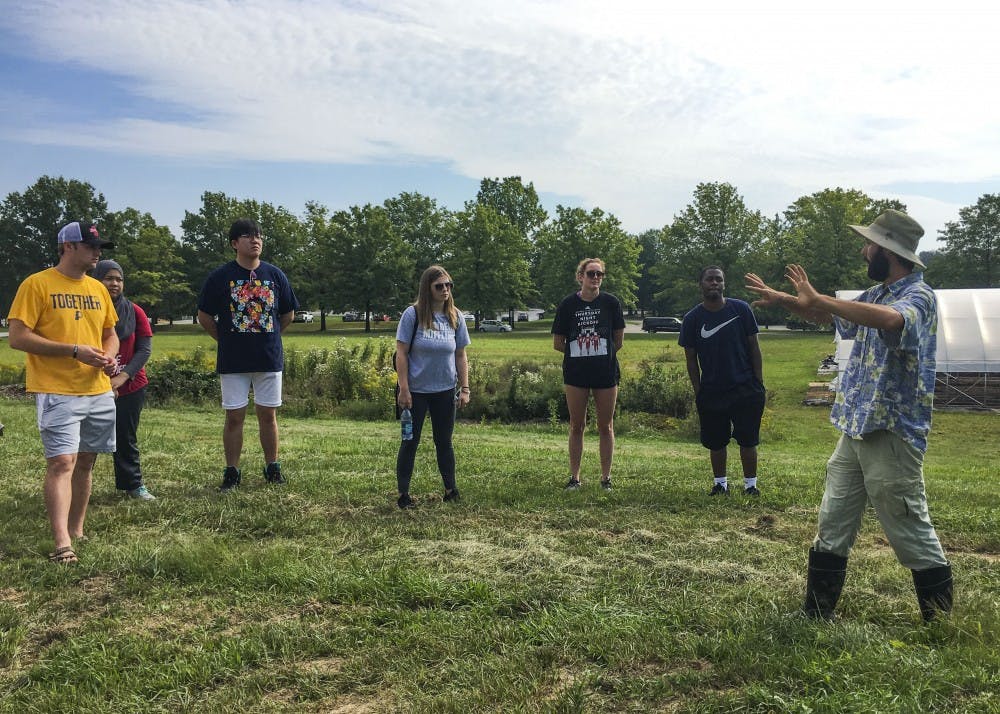

Wearing a blue Hawaiian shirt, black rubber boots and a sun hat, Erin Carman-Sweeney, IU Campus Farm manager and educator, stood next to long rows of plants ranging from tiny seedlings to sprawling, leafy butternut squash.

“I had prepared for the squash to take up the equivalent of four beds, the way my other ones are, but they’ve ended up taking up more than that,” 28-year-old Carman-Sweeney said. “Closer to six.”

He pointed out beets, tomatoes, peppers, carrots, spinach, cilantro, kale, beans, lettuce, dill, bell peppers, parsley, flowers, radishes and the unruly butternut squash.

It’s only about a fifth of the land the IU Campus Farm at Hinkle-Garton to grow food on, but it’s a start.

The IU Campus Farm is in its first season of growing food and welcoming students, staff and faculty to its grounds. The 10-acre farm uses and teaches sustainable, organic farming practices, provides opportunities for research and offers people a chance to connect with their food through hands-on work.

The farm was rooted in an idea cultivated by IU Campus Farm co-directors James Farmer and Lea Woodard and IU staff and faculty members. Farmer and Woodard wrote a grant proposal more than a year ago to fund their dream project of having a campus farm. Now, it’s a reality.

Right now, 90 percent of the food grown on the campus farm goes to dining halls, primarily the Indiana Memorial Union and Wright Food Court. The other 10 percent goes to local food pantries, such as Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard and the Crimson Cupboard food pantry, Carman-Sweeney said.

“Your average meal item on your plate has traveled over 1,800 miles to get to you,” Carman-Sweeney said. “Our food travels a mile or two.”

Woodard, who also manages Hilltop Garden and Nature Center, said the process of growing food, getting it ready for sale and selling it in different contexts will be one of the learning opportunities students will have on the farm, setting it apart from Hilltop.

“IU doesn’t have an agriculture department, so we’re kind of coming at this from a little bit of a different angle and perspective,” Carman-Sweeney said.

Farmer, also an associate professor in the School of Public and Environmental Affairs, has been on the faculty end of organizing the farm.

Some of Farmer’s fellow SPEA faculty members are planning soil science research projects and have classes based around the farm, but the professors who have been eager to get involved are not just from his corner of campus.

Professors from the Media School, the anthropology, biology, geography, creative writing and even informatics departments have all been excited to set up class visits to the farm.

Textiles professor Rowland Ricketts from the School of Art, Architecture and Design is trained in the Japanese methods of indigo farming and dying. He is growing indigo at the campus farm for his projects and classes.

“I had to have a flat surface, and the campus farm is great for that,” Ricketts said. “It has great sunlight exposure for drying as well.”

Rickett’s harvest was better than expected this year, Carman-Sweeney said. The land Ricketts used was part of large percentage of land that was stripped of its topsoil when developers were planning to build on the land. This soil must now be regenerated.

For Farmer, it was clear from the beginning that the practices used on the farm must be sustainable.

Farmer said he thinks regenerative and sustainable agriculture is the best way of producing food.

He said he also is aware that more research is needed on how to use these practices on a larger scale to feed more people.

“We need to be able to make an example of it for other people to learn from,” Farmer said.

One of the main sustainable practices the campus farm wants to focus on is soil health. Instead of using chemicals to fertilize plants and kill weeds, Carman-Sweeney and Woodard emphasized the need to use natural methods that do not harm the soil health.

Cover cropping is another way soil will be taken care of on the farm. They are not planted to harvest and eat but to put nutrients back into the soil, prevent weeds and erosion and attract pollinators between rotations of different crops.

“A couple inches of soil and the fact that it rains is what keeps us alive,” Carman-Sweeney said. “So I think it’s very important and something we want to emphasize here is regenerating the soil and maintaining its health because it’s a complex living system.”

While some sustainable practices take more manpower, Carman-Sweeney argues this is a good thing.

“Something I want to emphasize with this project is that we want to involve more people in agriculture,” Carman-Sweeney said.

He said the campus farm will exceed their goal of 1,000 students visiting the farm in the first year.

Volunteer work days also open up the farm to anyone wanting to get their hands in the dirt. Work days are on Fridays from 12:30 to 4 p.m. and Saturdays from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. at the farm which is located at 2920 E. 10th St.

“So many of us work jobs that you sit at a computer all day,” Carman-Sweeney said. “People don’t feel that their work is very meaningful. Growing food is very meaningful.”