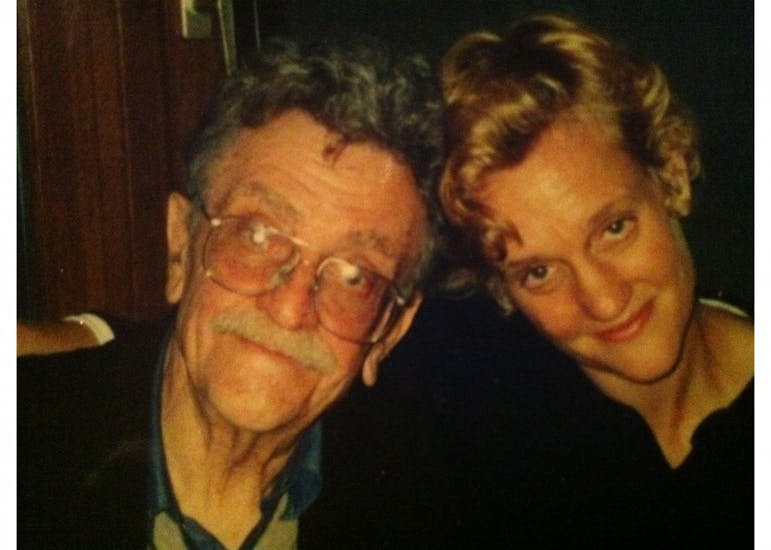

On an annual pilgrimage to Indiana, Nanette Vonnegut, daughter of legendary author Kurt Vonnegut, visited the Lilly Library to see its collection of her father's original manuscripts.

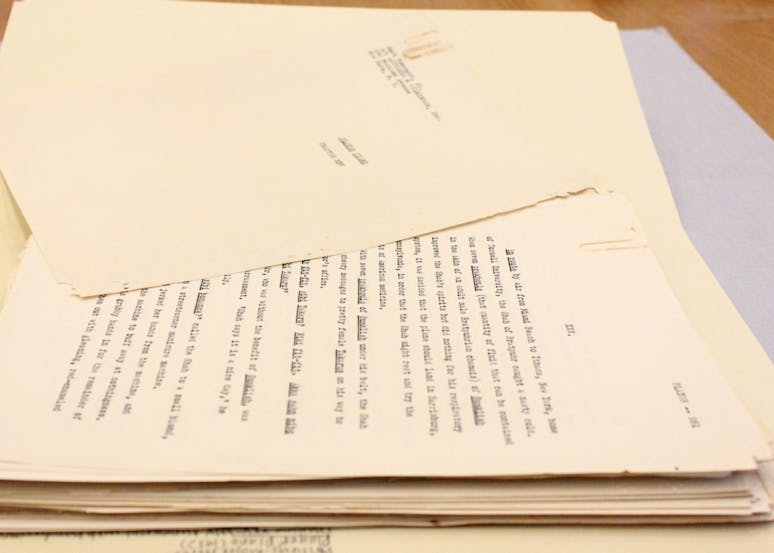

“They’re precious now; growing up, they weren’t precious,” she said. “They were on the ground, coffee-stained, with ashes from his cigarettes. They were my childhood; I just wanted to see them again.”

Kurt Vonnegut’s manuscripts are sprawling and messy, filled with starts and stops, drafts and redrafts. Nanette Vonnegut says they’re a reminder of his hard work.

“Seeing his collection is a really beautiful thing,” she said. “And I’m really heartened by how it’s being taken care of.”

The Vonnegut manuscript collection at the Lilly Library contains about 6,000 items, including early rejection slips, drafts, doodles, and fan letters, said IU Libraries assistant librarian Isabel Planton.

"The multiple drafts of some works in the collection, such as 'Slaughterhouse-Five,' demonstrate how hard Vonnegut had to work to achieve his desired effect with his writing," Planton said.

A resident of Northampton, Massachusetts, and an artist herself, Nanette Vonnegut comes to Indianapolis on invitation from the Vonnegut Library nearly every year. On Monday evening, she’ll speak at the library about her maternal grandmother’s mental health.

“I’m going to bat for my grandmother,” she said, chuckling. “But always, I’m going to bat for my father.”

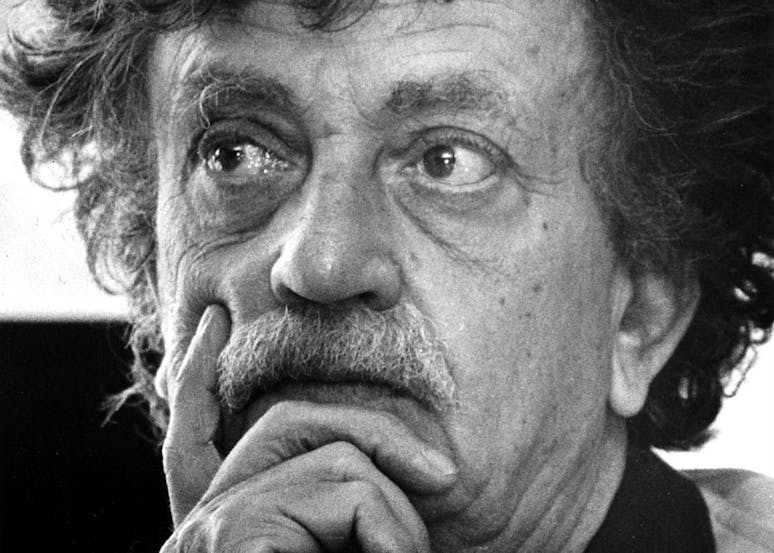

Being the daughter of a writer isn’t as romantic as it sounds, Nanette Vonnegut said.

“What I saw was a moody guy," she said. "Now I get why he was moody."

He toiled away all day long in his study in the family’s Cape Cod home, entering in the mornings and often not emerging until the evenings when it was time for dinner or cocktails. Nanette Vonnegut and her siblings knew not to bother him while he was at work, she said.

“My mother was sort of the gatekeeper,” Nanette Vonnegut said. “She believed in him, was invested in him, because she knew he was different from anything she had ever read.”

Her mother was a literature major, an academic and a caretaker. She took care of the children while her husband wrote, wrote, wrote.

Many people think of Kurt Vonnegut as a solitary or anti-social person, but that wasn’t the case, Nanette Vonnegut said. She recalls a time even before his fame when Jack Kerouac came to visit the family’s home.

“He wasn’t cool with Jack Kerouac’s drunken behavior and swearing,” she said. “So, he said, ‘he’s gotta go.’ He had his standards.”

Later, when he moved to New York after gaining traction as a writer, he enjoyed the business, she said. He was always doing something.

“The guy was never idle,” Nanette Vonnegut said. “If he wasn’t writing, he was doing paintings. It was an exciting house to be in. He was a creative force, and my mother was also very sparkly and very positive.”

Despite her father’s need for privacy when he wrote, he was a tender and loving figure in Nanette’s life. He was surprisingly funny, out of nowhere, she said. She remembers him chasing her and her siblings around the house, bread crusts jammed in his mouth to imitate fangs.

But that didn’t last forever.

“It was sort of the end of this, the family unit,” she said of her father’s move to New York when his writing career finally began to garner recognition.

Kurt Vonnegut moved to New York in 1971, and soon after divorced his wife. They remained friends, but to Nanette Vonnegut, it was the end of an era both for her father’s personal life and for what she considered the best portion of his writing career.

“That’s where his formative writing time was: on the Cape,” she said.

Nanette Vonnegut said her favorite of her father’s works was “Slaughterhouse Five.”

“It’s a magic trick to me that he condensed something so traumatic in such short order,” she said. “It’s brilliant. It’s a masterpiece of condensing trauma into how he wrote around what happened to him.”

After a moment’s consideration, though, she said her favorite was probably just whichever novel he’d written the most recently.

“I’d be a fan if I were not his daughter," she said.

But most of all, she said, reflecting on seeing his manuscripts at the Lilly Library, his talent was genuine, and his fame was born of hard, hard work.

“He’s a good thing,” she said. “He’s a good thing in the world and a good force. He has staying power. I am very proud of him.”