Although the Americans with Disabilities Act was signed into effect almost 18 years ago, people with disabilities are still facing lack of accessibility in the most basic of places, including Indianapolis public transit.

The Americans with Disabilities Act was passed in 1990 as a civil rights law that prohibited discrimination on the basis of disability. In broader terms, this means that employers cannot deny a job based on disability, public places need to provide accommodations for people with disabilities.

Accessibility means different things for different people, but at its core, it means that everyone should have access to the same public places — public transit, for example.

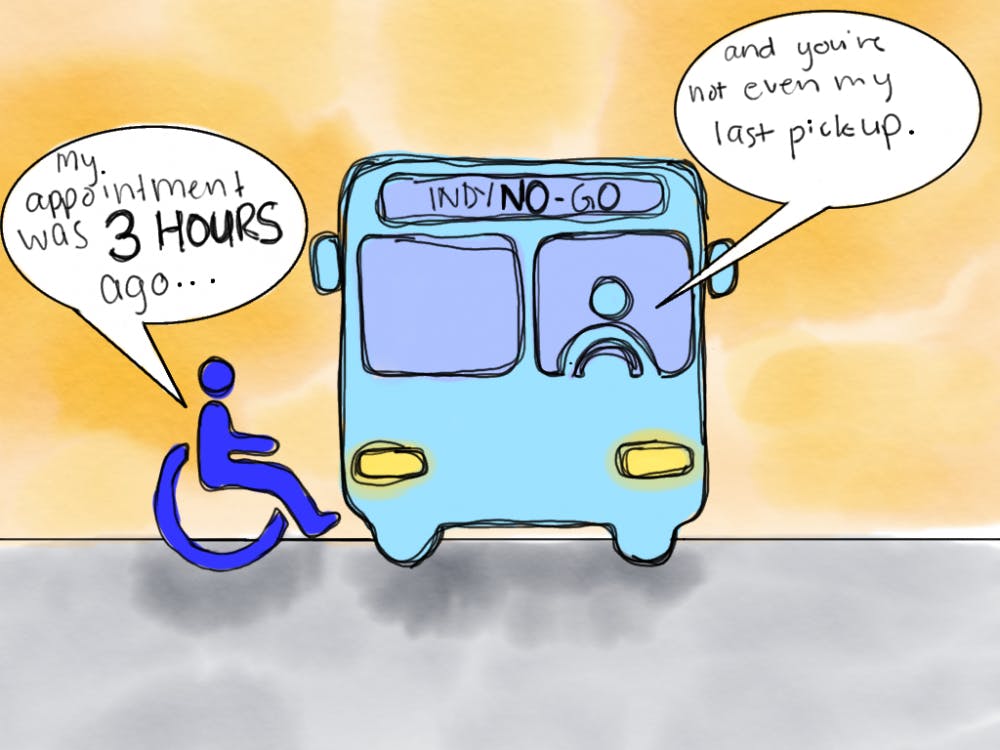

In Indianapolis, IndyGo is the mass public transit bus system. In theory, it works exactly how Chicago buses or D.C. buses work. In practice, its system is even more unreliable than the metro in D.C.

Not only is the entire system faulty and unreliable, but the buses of IndyGo that fit ADA requirements are even worse.

IndyGo regular buses are often not equipped with the resources to safely transport people with disabilities, such as wheelchair lifts and restraints. This means that IndyGo OpenDoor transit is kind of a separate system itself — and not a better one.

As far as accommodations within the buses go, IndyGo could look to IU as an example. IU buses are not perfect, but most are equipped with wheelchair-friendly technology, auditory cues for people with visual impairment and visual cues for those with hearing deficiencies on every single bus, regardless of route. IndyGo could begin integrating these traits for a lower cost than redoing the whole system, and it would make a world of difference.

In Marion County, over 4,000 people are currently registered to use OpenDoor transit. Legally, once people have completed the application process and paid their fare, OpenDoor has to serve them. This would be a really great thing if only the resources were there.

There are not enough ADA compliant buses in this program to effectively help everyone who depends on it.

Because there is no set route on the OpenDoor service, as customers and places change daily, OpenDoor cannot even provide its patrons with a concrete schedule to rely on. Instead, OpenDoor tells people that it will be anywhere within a 30-minute window.

If you’ve ever been told that something would be arriving within 30 minutes, you know that it can be unreliable.

Yet instead of your pizza arriving 45 minutes late, imagine your only transportation to important appointments and work is 45 minutes late.

Employers don’t want to hear that you are late because of your bus, and it’s already difficult for people with disabilities to find work, despite efforts to eliminate discrimination.

In an interview with WTHR News, Dan Scharbrough said his bus is almost always late, resulting in several lengthy wait times on hold with OpenDoor’s reservation service. When the bus finally does come, he will already be late to his appointment — but the bus has another pickup in the opposite direction.

Several physical therapists and doctors have strict late policies and missed appointment thresholds, and cancellations occur due to patients not wanting to waste a crucial appointment.

Another rider who wished to stay anonymous stated that she was hospitalized after missing a dialysis appointment when the OpenDoor bus was three hours late, forcing the cancellation of a life-saving treatment.

It feels like IndyGo devoted little time and money to a system just to legally say it met ADA standards — but in practice, the system is hardly a functioning one.

Even the cost is inaccessible to those who cannot work due to disability and fixed income. A full fare 31-day bus pass for the regular IndyGo buses is $60. Yet for OpenDoor, it only offers single-trip passes and for 31 days that amounts to approximately $110.

People who rely on OpenDoor are paying nearly double what people who can use the regular system are, which is another roadblock in providing equity.

Unfortunately, the easiest fix to this problem is to spend more money on the system. It makes sense that these buses use more expensive technology, but we need to increase the number of buses so that reliable routes are possible.

Nobody wants to pay higher taxes, but taxes are what keep our homes, roads and schools afloat. Not always, but most times, the higher a property tax is means the home is worth more, meaning the owner makes more. Especially within the past five years, Indianapolis has seen a huge realty surge in certain areas. This has created gentrification and raising prices of rent and mortgages due to the influx of new money.

If you can afford to live in a house worth a quarter of a million dollars, have a job that provides that security and require no special accommodations to do regular day to day tasks, wouldn’t you be willing to pay a few dollars more to make sure someone has the ease of getting to work just like you do?

By increasing municipal property tax, in theory, more money could be generated to benefit the transportation system. A long-term goal would be to integrate the OpenDoor system back in line with how IndyGo works in terms of schedules, passes and planning.

Getting to work or appointments on time takes up no real estate in an able-bodied person’s mind, so it shouldn’t for people with disabilities either.