From March 9 to May 31, 2010, performance artist Marina Abramović sat in New York’s Museum of Modern Art for 736 hours. Over 1,554 visitors sat in a chair across from her. Abramović remained silent and unmoving for all of them.

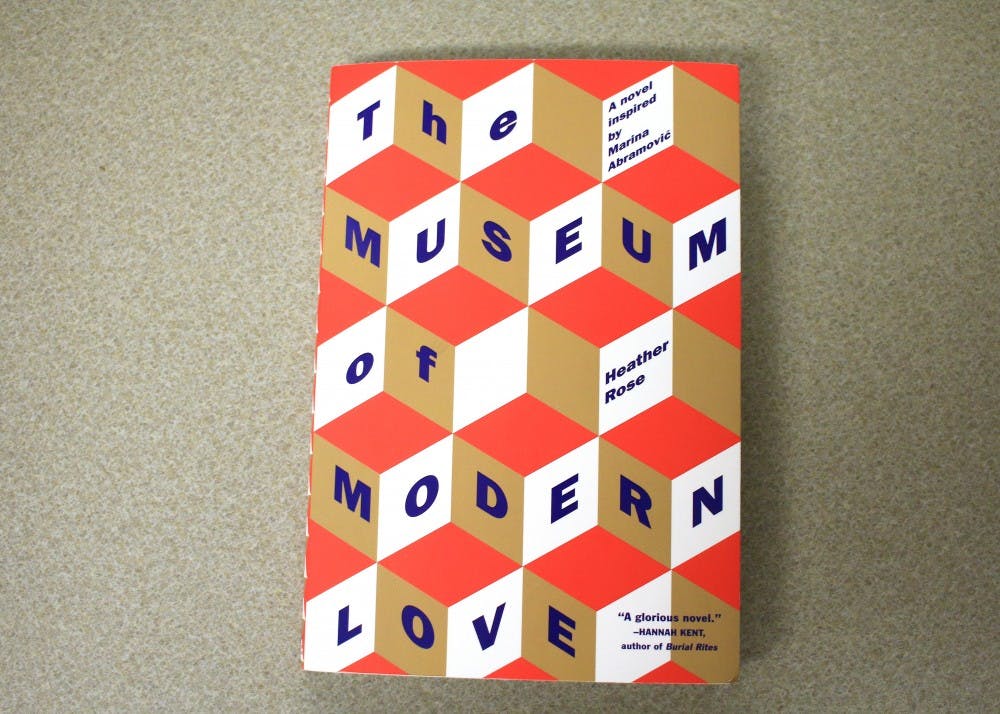

Heather Rose’s American debut novel “The Museum of Modern Love,” released on Nov. 27 is based on the actual presentation of this exhibition.

The novel follows semi-successful composer Arky Levin after his wife orders that he not visit her while she attempts to recover from a serious illness. He has trouble creating music as a result, until he witnesses Abramović’s performance and becomes overwhelmed by the power the simple act of two people sitting and staring at each other has over him.

For many characters in the novel, Abramović’s sitting, titled “The Artist is Present,” is an emotionally gripping work of art. Some experience revelations and epiphanies about their own relationships and love. For Arky, the opportunity to sit and uncover truths about his past by sitting across from her is tantalizing as it is terrifying.

Though the arc of the story is relatively small, his character is explored with enough interesting depth. The strongest selling point is his struggle to come to terms with his wife — in her failing health, she has ordered him not to see her because she loves him. The story is told by an unnamed, but interposing, third-person narrator who explains Arky’s thoughts.

Despite the small plot, the exploration of the fictionalized Abramović is intensely interesting. Much of the artistic work of the real-life Abramović appears in the novel. This includes “Lovers,” where she and her husband walked toward each other across the Great Wall of China before divorcing and “Breathing In/Breathing Out,” where they locked mouths and breathed into each other until they collapsed, unconscious. The novel is as interested in exploring Abramović’s history and growth as an artist through these experiences as it is with Arky.

The story falters in its incessant philosophizing and pontifications on the status of art. Bystanders of “The Artist is Present” constantly try to define Abramović’s artistic statement, and beyond that, the definition of art in general. Much of the narrative style is poetic to the point of philosophical banality. In a casual conversation, one character teases Arky after he admits he is afraid of the stars.

“It’s just emptiness. In fact, it’s the past rushing at us. Everything out there, other than the sun, died years ago.”

While these types of sentiments are pretty, Rose’s desire to cram as many poetic lines into the story as possible left me with a cloying dullness. Everything was grand and dramatic, so nothing was. Especially in the non-narrative parts of the story, such as backstory and wide berths of thought explanation, the poetics descend into abstraction, such as when the narrative extrapolates on the line, “Grief was a threshold thing that lived at the heart of the inevitable.”

These kinds of lines, scattered throughout the text, leave the reader glazing over empty, ungrounded paragraphs.

Some characters were unnecessary. Jane, a tourist from Georgia, comes and goes, affecting little about Arky or the plot itself. For a story about one guy, it isn’t warranted to introduce a deep backstory and spiritual change for these secondary characters if those characters don’t affect the protagonist.

Despite these issues, some scenes are still quite vivid and incredibly interesting. Those interested in detailed explanations of the idea of art, and what it can be, will find a lot in this novel. Even when this line of pondering lapses into purple prose, the odd nature of Abramović’s exhibition and Arky’s response to it warrant the read. The way Rose wrote Marina Abramović’s backstory could easily have been a novella by itself.