The tangled legacies of two men who shaped IU's history collide in one campus gymnasium.

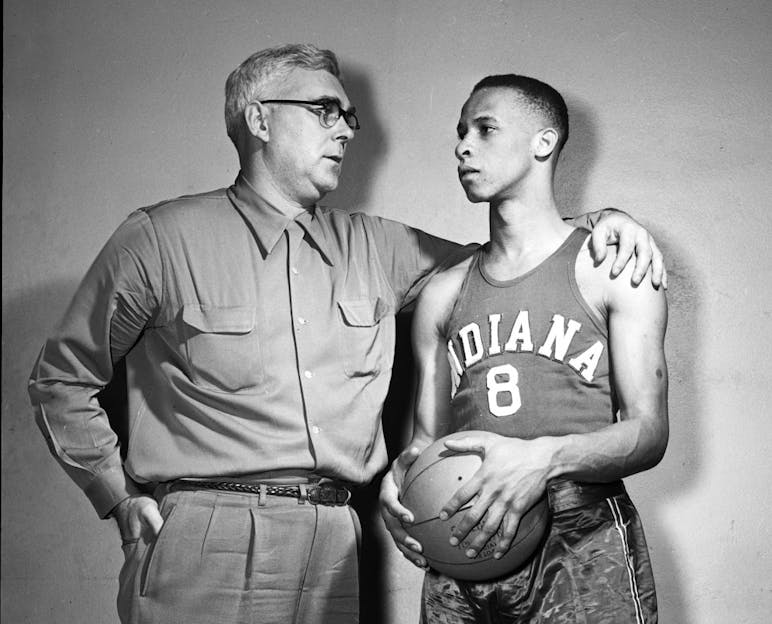

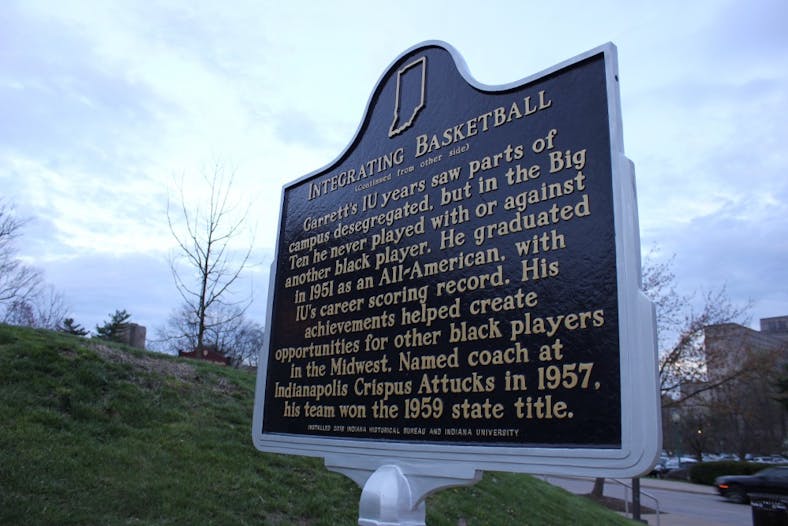

Legendary basketball player Bill Garrett set records for scoring and rebounding in the Fieldhouse. Under that same roof, he also broke the Big Ten's color barrier that barred black players.

At the same time that the 6-foot-2 center was transforming IU and Big Ten basketball, another campus figure, trustee Ora Wildermuth, wanted to stop integration.

“I am and shall always remain absolutely and utterly opposed to social intermingling of the colored race with the white,” Wildermuth wrote in a letter in 1945. “I belong to the white race and shall remain loyal to it. It always has been the dominant and leading race.”

Garrett was honored as an All-American his senior year. At his final game with a crowd of 10,000 fans, he received a standing ovation.

Twenty years later, the Fieldhouse was renamed. It was named not for the trailblazing player that integrated its courts, but for the white trustee who wanted to block progress — Ora L. Wildermuth Intramural Center.

IU has long grappled with how to untangle the mistake. The Board of Trustees voted in October to strip the building of Wildermuth’s name, shortening it to the Intramural Center.

This week, IU’s men’s and women’s basketball teams will take to the court in special uniforms to honor the 70th anniversary of Garrett's historic start at IU. The men's shooting shirts will feature his silhouette. But some of Garrett's supporters say more can be done.

The old Fieldhouse, they say, ought to bear his name.

The university hopes this year to put a new name on the building. The choice will reveal how IU chooses to tell the story of its history.

***

Across the country, letters are being peeled off and name plates are being taken down from university buildings that honor people with troubling views or a troubling past. It’s happened at Yale University, Stanford University, Duke University and many other schools.

Wildermuth’s name is not the only one that has concerned IU students.

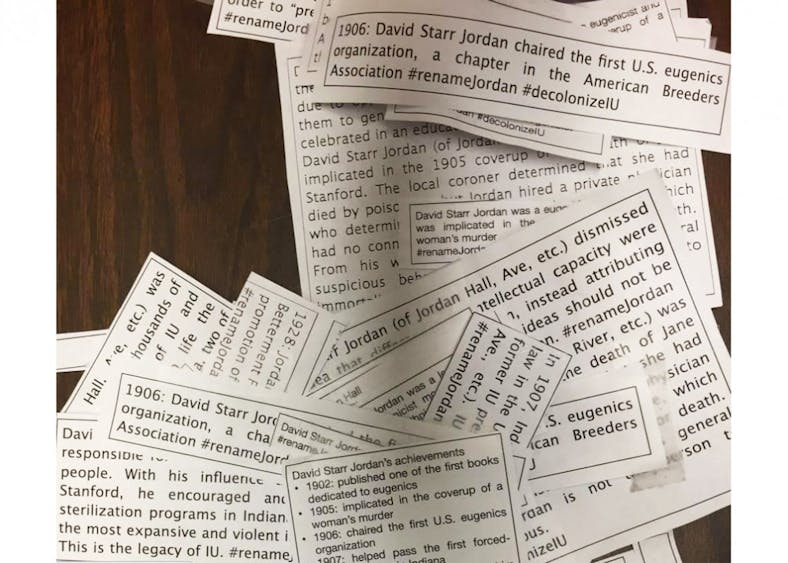

In 2017, anonymous fliers circulated in Jordan Hall decrying the practice of eugenics promoted by former IU president and scientist David Starr Jordan, who advocated for forced sterilization.

According to his biographer, Jordan once said, “To say that one race is superior to another is merely to confirm the common observation of every intelligent citizen.”

Jordan’s name was stripped in 2018 from a Palo Alto, California, middle school. But at IU, his legacy is ever-present — in Jordan Hall, presumably on Jordan Avenue and even in the little brook that cuts through campus, known as the Jordan River.

A 2017 controversy over the Thomas Hart Benton mural in Woodburn Hall 100 also speaks to how symbolic representation of the past can sour the present. The mural titled “Parks, the Circus, the Klan, the Press” portrays Indiana history and depicts the Ku Klux Klan in white robes alongside a burning cross.

Students petitioned to have the mural removed. Provost Lauren Robel, in a statement sent to the campus, said the university had to balance preserving the mural with offering an inclusive learning environment. The mural actually celebrated the press for breaking the Klan’s political influence in the state, but that point was easy to miss in a classroom setting.

“This question becomes especially urgent whenever events such as the march of white supremacist groups in Charlottesville and the current national debate over Confederate monuments occur,” Robel said. “These broader conversations become deeply local, and we must come to a decision as a community on how to handle public art and memory.”

In her statement, Robel announced classes would no longer take place in Woodburn Hall 100, and that the space should be used as a gallery or for public lecture, where the larger point of the mural would be more easily conveyed.

History shapes the present. But the way the past is interpreted is changing, too.

***

More than 40 years before the building carried his name, Wildermuth advocated for the Fieldhouse to be built.

He gave a speech at its dedication in 1928 promoting exercise for young men in an increasingly mechanized world where “a button pushed floods the house with a glow of light.”

Wildermuth, born in 1882, described in his speech people waking up before sunrise, lighting a lamp and gathering wood to heat the kitchen.

“The boy of today may live with no more arduous physical exercise than picking his teeth or taking a bath,” Wildermuth said.

He enrolled at IU in 1902, then became one of the original residents of Gary, Indiana. He served there as a teacher, judge, librarian and president of the Gary Bar Association.

Wildermuth was president of the IU Board of Trustees from 1938 to 1949. He dedicated 27 years of his life to the board and the advancement of the university. He worked for IU during an era of transformation and expansion.

But for many the depth of his accomplishments was undercut by his views. He completely opposed integration, from housing to socialization to interracial marriage.

He told former IU President Herman B Wells, in a letter from 1942, that a teacher who told a class “colored people are just as good or better than white people” should be fired.

Wells, the stout IU legend, helped transform IU into an internationally recognized university. He was Wildermuth’s trusted colleague, but he didn’t share his views.

The campus pool at the time barred black swimmers. So one day Wells took black football player J.C. Coffee, who friends called Rooster, to the pool. Wells had him jump in, and from then on, the pool was desegregated.

Some say Wells was a silent advocate for racial justice.

Wildermuth died in 1964.

The Intramural Center was named for him in 1971. Wells remarked at the naming ceremony that Wildermuth influenced so many parts of the university including the law, medical and music schools as well as the libraries and physical plan of campus.

“I am both pleased and gratified that from this day on the name of Wildermuth will be familiar to every student and those that use this center will pay tribute to its virtual founder through perpetuating his name,” Wells said.

For decades, students worked out in the gym which many called the WIC.

In 2006, Wildermuth’s words resurfaced in a book and sparked an effort to have the building renamed.

***

Alumnus Tom Graham grew up in the same town as Bill Garrett. Graham was 4 years old when Garrett won the state championship with Shelbyville High School.

Garrett was one of Graham’s heroes. So Graham and his daughter, Rachel Graham Cody, wrote “Getting Open: The Unknown Story of Bill Garrett and the Integration of College Basketball.”

They spent hours combing through IU's archives and interviewing anyone connected to Garrett’s story.

Their book, published in 2006, exposed Wildermuth’s blatantly racist views.

It also started a conversation.

IU President Michael McRobbie tasked the university naming committee to consider the building’s namesake.

The trustees considered in 2009 renaming the gym the William L. Garrett-Ora. L. Wildermuth Intramural Center, placing the name of a civil rights pioneer and a racist together.

The proposed change was swiftly put to an end after complaints from Garrett’s family.

“That will not happen in any circumstance, to share a name with a strict segregationist,” his wife Betty Garrett said.

One administrator spoke out to clarify the reasoning behind the university's decision.

"From the very start it has been our goal to recognize Bill Garrett and honor his achievements at IU," former IU vice president Terry Clapacs said in a release. "We believed that we had the blessing and support of the Garrett family, but we now have learned that is not the case. So the university will respect their wishes, and we will not proceed with this decision."

The fiasco received attention from local news, the Chicago Tribune and ESPN.

Still, Graham and other advocates were determined to see Garrett’s name on the building.

***

Nearly 10 years have passed since the Garrett-Wildermuth debacle.

A state historical marker was placed in 2017 outside the School of Public Health and once-Wildermuth Intramural Center that reminds passers-by of Garrett’s historical importance to IU. Wildermuth’s name on the standard campus sign lingered in the background as the marker was unveiled.

Maybe this was the physical reminder of the incongruity that pushed the trustees to act — or maybe it was Graham and his group of advocates.

In March 2018, Graham and three others — his daughter Rachel, former Herald-Times sports editor Bob Hammel and IU emeritus history professor James Madison — petitioned the Board of Trustees to get Wildermuth’s name off the building and to rename it for Garrett.

Black students were once banned from dorms, honor societies and the campus swimming pool, the petition pointed out. IU once accepted no more than 84 black women per year because that was the maximum number of rooms available to house them.

Then came Garrett. He became an outward symbol of integration. In a follow-up letter, the group sent a strong message about Wildermuth.

The name is an ongoing affront to core principles that IU stands for, and its removal would enable IU to tell the full story of its transition from segregation to integration, the letter said.

In October, by a 7-1 vote of the trustees, the university agreed.

McRobbie announced at the October trustees meeting that he appointed a group of trustees and representatives from the university naming committee to consider removing Wildermuth’s name.

The committee ultimately decided the name should be removed. The board affirmed it.

The trustee who voted against removal was Pat Shoulders. While he said he found Wildermuth’s comments loathsome, they need to be considered in context.

“The state of Indiana outlawed interracial marriage until after he had died, the IU campus was segregated, and some studies show that up to 30 percent of white males in Indiana were members of the Ku Klux Klan,” Shoulders said at the meeting.

Wildermuth was president of the Board of Trustees when Garrett was playing, Shoulders pointed out.

“It would not have happened if Wildermuth determined to stop it,” he said.

An IU spokesperson said the members of the Board of Trustees did not want to comment further on the name removal.

Now the sign that once displayed the trustee’s name simply says Intramural Center.

***

Tina Garrett didn’t fully grasp her father’s legacy as a pioneer for black students on IU’s campus until she was an adult.

“My father was a man who played basketball,” Tina, 63, said. “He wasn’t just a basketball player. He was a person who I think just represented the spirit of Indiana University as as early as the 1940s.”

She grew up knowing her father as a coach. During basketball season, her family would always eat late, around 8 p.m., after Garrett returned from practice at Crispus Attucks High School in Indianapolis.

She didn’t realized what an extraordinary player he was until he died.

“As a person, he was just spectacular,” Tina said. “He was like a quiet soul. He was this man with all this confidence, but he was really humble.”

Naming a building after him would start a larger discussion about IU’s values, Tina said.

“To me, it would be such an honor for my dad’s name to be on the building,” Tina said. “I just think about how his legacy will live on.”

A permanent name for the building is under consideration, IU said in a press release, and will likely be revealed this year.

For now, the old Fieldhouse remains the Intramural Center.

Graham and the group are still pushing for Garrett’s name on the building.

“IU goes big or goes small,” Graham said. “Going big would be acknowledging the segregation, telling history candidly. Told as a whole, it’s a very good story.”