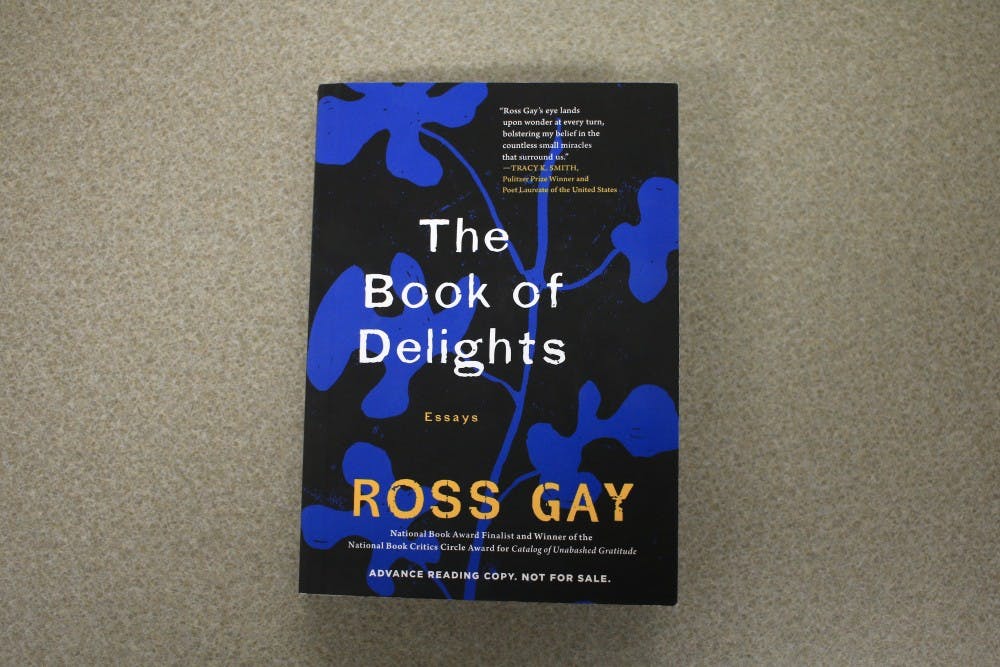

IU professor and poet Ross Gay’s “The Book of Delights” was released Feb. 12. Gay’s idea for the book began with a simple premise, discussed in the book’s preface.

“One day last July, feeling delighted and compelled to both wonder about and share that delight, I decided that it might feel nice, even useful, to write a daily essay about something delightful,” he wrote.

From the time he turned 42 to when he turned 43, Gay wrote 102 micro-essays on just those things — sources of delight.

The essay compilation is by no means a sentimental, Hallmark-card collection of cliches, nor is it heavy with philosophical analysis. It falls somewhere between, marked by sincerity, grounded in concrete experiences and defined by optimism.

The book is filled with moments of little beauty as much as it is wonderful language. Lines read, “It might be that the logics of delight interrupt the logics of capitalism” and “I love not getting the groceries in from the car in one trip.”

Gay’s sincere, conversational style renders these joys in small, loving language. His examination of the mundane carries a sense of infinity, wisdom and compassion for the world around him.

In Chapter 14 “Joy Is Such a Human Madness,”’ Gay reflects on a student, Bethany, talking about her aspirations as a teacher and what she wanted her classrooms to be like, when she said “What if we joined our wildernesses together?”

“Sit with that for a minute,” Gay writes. “That the body, the life, might carry a wilderness, an unexplored territory, and that yours and mine might somewhere, somehow, meet. Might, even, join.”

Whether he describes digging in a garden, scoring on 12-year-olds in pickup basketball or peeing his pants, Gay renders these micro-essays with surprising and unrelenting compassion. Each delight comes from a place in his own life — his experiences with odd vernacular sayings, examining different statues around campus or the childhood concept of the do-over.

Even the not-so-beautiful moments, such as being racially profiled at a pawn shop or his bad dream of having sex with his mother, are explored with a determination and often end on a note of optimism.

“Very few things have been as delightful as when I woke from that dream, let out a groan, shook off the grossness, and shouted ‘Thank you! Thank you!’ to no one but me,” Gay wrote.

“The Book of Delights,” in its examination of the world, is eager to remind readers of their curiosity. It wants to nudge them against the borders of everyday moments and observe them a little more closely, in hopes that they’ll find the little worlds within.

No essay forces a moral lesson on the reader. Gay's love for language and the world arises out of the text and inspires the reader in nondidactic ways.

Gay reflects on music, art and the effects they’ve had on him, citing Donny Hathaway’s song “For All We Know.” While the phrase is cheap when other singers use it, Gay wrote, Hathaway uses the phrase to talk about dying and disappearance in a way that might summarize much of Gay’s tender philosophy.

“His is a voice that makes you realize that your voice is the song of your disappearing, which is our most common song,” Gay wrote. “The knowledge of which, the understanding of which, the inhabiting of which, might be the beginning of a radical love. A renovating love, even.”