The shoes of Lilly King are going to be nearly impossible to fill. No one else on the team wears Crocs on the awards podium.

Her time swimming for IU came to a victorious close March 23 in Austin, Texas as she rose from the water after winning her race. She looked back at the crowd and held up eight fingers.

King had won the 200-yard breaststroke at the 2019 NCAA Women’s Swimming and Diving Championships. It marked her final collegiate race and her eighth NCAA title.

Each of King’s eight fingers represented one of her national championships as she solidified herself as the winningest female breaststroker in NCAA history.

It wasn’t always that easy.

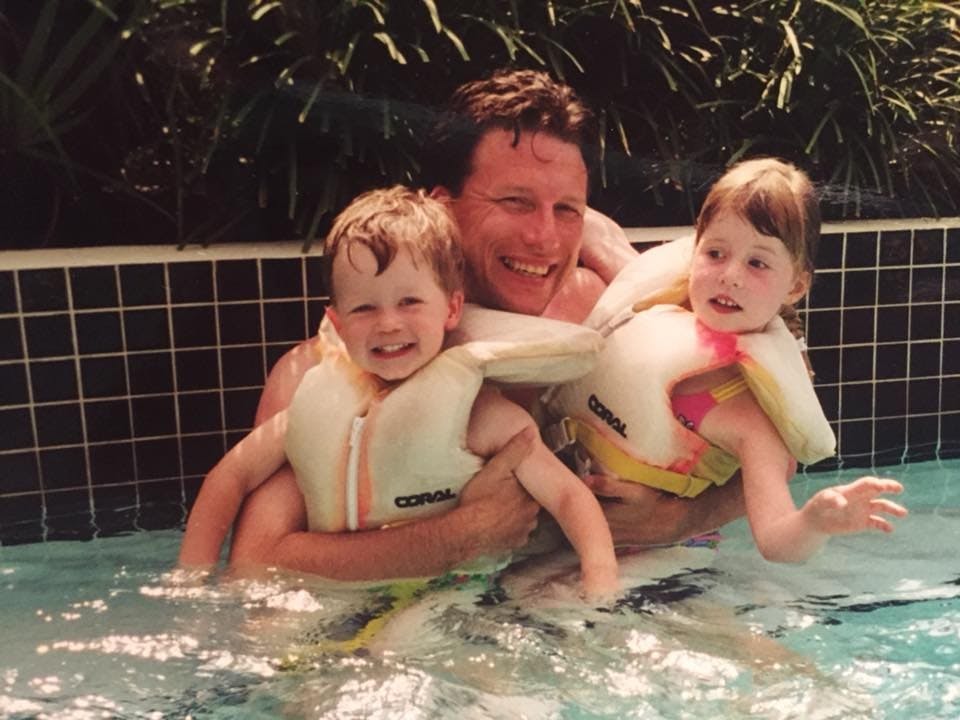

When King was 7 and started swimming, she wasn’t winning races.

“She was not good when she started,” King’s mother, Ginny, said. “It took her probably three years before she could beat people.”

Her love of the sport kept her with it. She began to work harder than the other swimmers, a trait that has followed her through her life.

“Seeing who I could catch at the next race, checking people’s names off a list or just getting faster, beating the boys in practice, those little things all added up and that’s why I am where I am today,” King said.

At 12, King swam in her age group state title meet. It was a day that changed her life.

“All day I was saying, ‘I’m gonna win, I’m gonna win,’” King said. “I think that one race taught me if I really believe in myself, I can do anything I put my mind to.”

King won the age group state title, signaling to her and those around her that her work had paid off, her ability as a swimmer finally coming to fruition.

“That was the first indication that like, ‘Oh, she might be pretty good,’” Ginny King said.

After getting the first taste of a major victory, King wasn’t about to relinquish it.

King may never have been the most talented swimmer growing up, but she was determined to outwork everyone.

“That really stuck with her that she could outwork other people,” Ginny King said. “She’ll race anybody, it doesn’t really matter. When she was a kid she’d race the boys, she’d race the big kids it didn’t matter.”

King's work ethic was unparalleled, said David Baumeyer, her coach at F.J. Reitz High School in Evansville, Indiana.

Reitz never had high-end facilities — or even its own pool. The entire swim team got just four lanes a day at Lloyd Pool, a public pool in Evansville, and often had to share time. The facilities were in disrepair, King said. She didn’t even have her own locker.Even with the obstacles to her development that Lloyd Pool presented, King continued to get faster.

She broke the Indiana high school state record in the 100 breaststroke and swam in multiple Junior National events. King’s name was becoming well-known to college coaches.

Having competed at numerous national meets and dominating Indiana high school swimming, King was a sought after recruit. She made a list of what she was looking for in a school. She wanted a school where the men’s and women’s teams shared a head coach. The head coach also had to be the breaststroke coach. Most importantly, King wanted a school that would help her prepare for the 2016 Olympics, set to take place after her freshman year.

The University of Tennessee fit all of those requirements for King and quickly became one of her favorites.

IU Head Coach Ray Looze wasn’t going to let a top in-state talent like King head south to Knoxville, Tennessee. No coach worked harder to recruit King than Looze.

“When she was born, I talked to her mother,” Looze joked. “Whatever the NCAA limit for visits is, I did that. There’s a joke that maybe I should have gotten an apartment down in Evansville.”

“Ray was just absolutely persistent,” King said. “I can’t say it any other way. He was always calling. You could only call once a week, so once a week every week. On July 1, which was the first time that we could have in-person contact, he was at my doorstep at 10 a.m.”

Eventually, Looze was able to convince King to take a visit to Bloomington. IU had a meet against Tennessee that day, and while Looze was able to get her on campus, King wasn’t there to see IU, at least not at first.

“I expecting to really fall in love with how Tennessee was, and it was the complete opposite,” King said.

King got the chance to see IU’s campus and interact with the coaching staff. But it was the meet itself that changed King’s mind.

“Then I got to watch the team on deck at a meet and it totally changed my rankings as far as what schools I was going to,” King said. “That was a big turning point for me in the recruiting process.”

Inside of a Walmart with her mother, King said she didn’t want to go on a trip they had planned to visit the University of Florida. She had made up her mind. She was going to IU.

“She’s somebody that’s just true to herself,” Ginny King said. “She took a lot of flak when she went to Indiana initially. ‘Why didn’t you go to Texas, why didn’t you go to Cal?’ She kind of stood on her own and made that decision.”

While King had limited resources to train in Evansville, the facilities and coaches in Bloomington allowed for King to push her training to a higher level. It was the type of jump that both she and those around her expected her to make once reaching college.

As a result of that increased training, King quickly emerged as one of the top young swimmers in the nation. In her freshman year, King won the national championship in both the 100- and 200-yard breaststroke, and was named the College Swimming Coaches Association of America Swimmer of the Year.

King was one of the favorites heading into the Olympic trials. In her training, King said she swam a time that would have qualified her for the 2012 Olympics. She knew her times in training were going to be enough to get her qualified in 2016 for the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro as well.

“Basically trials for me was just don’t screw up,” King said. “ I had it in the bag.”

It wasn’t until King’s improvements her freshman year of college that Olympic gold seemed at all a possibility. But King had her sights set on it for years.

“She didn’t make trials, and she wasn’t devastated,” Ginny King said. “But then the Olympics rolled around and she was really mad that she wasn’t there. And she had no shot in 2012 of making the team. But it was like, ‘That’s where I belong.’”

In King’s junior year of high school, Rebecca Soni, who won the gold medal in the 200 breaststroke at the 2012 Olympics, retired from swimming.

Baumeyer walked into practice that day and King came up to tell him the news.

“And she says, ‘That’s one less person I’m going to have to beat,’” Baumeyer said. “I think that showed a little bit of her confidence, but I’m thinking, ‘That’s a long way down the road.’”

Confidence is an important part in the personality of Lilly King. It’s a confidence that began for her in competition, sibling competition to be exact.

King and her brother Alex are just 11 months apart in age. For them, everything was a competition.

“When we would race to the car, race to put our seatbelts on, race to get out chores done, things like that, it made racing not as stressful for me,” King said. “That might be where my confidence came from. Winning over and over again tends to help with that.”

Alex is now a sophomore backstroker on Michigan men's swim and dive team.

The rest of her family shared that confidence.

“In 2016, after NCAAs and she broke the American record, we bought our tickets,” Ginny King said. “We bought our plane tickets to Rio before trials.”

King cruised through trials, finishing first and clinching a spot in the 2016 Olympics.

While a contender for the gold, King didn’t head to Brazil as the favorite in the 100 breaststroke. That was Yulia Efimova, a Russian who was competing amidst controversy. Efimova had just come off a suspension for doping in time for the Olympics.

The Olympics marked King’s first time on the top U.S. team. Most the world had never heard of her. A hidden camera placed by NBC in the ready room changed that.

After Efimova’s semifinal heat of the 100 breaststroke, King was caught wagging her finger at a shot of Efimova on the television. It was a moment that created national attention for King’s eventual final heat of the event against Efimova.

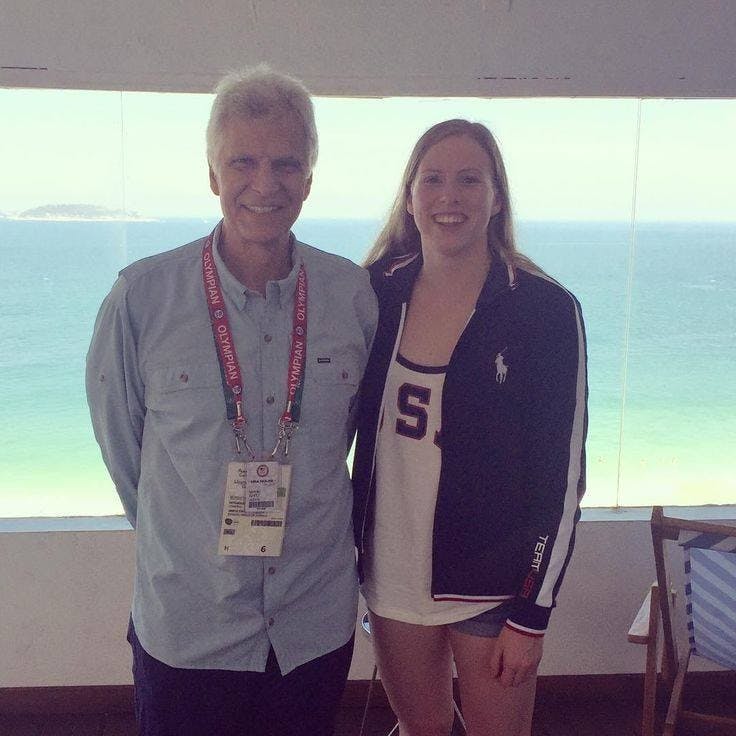

“We have some lions on the team,” said David Marsh, the head coach of the 2016 U.S. Olympic women's swimming team. “I know the world already knew that Michael Phelps is a lion, but I don’t know that the world knew Lilly King was a lion.”

King's finger wag quickly became a focal point at the Olympics games. She had no idea anyone even saw it.

“That night it all just came out,” King said. “Honestly, I didn’t know I was being filmed. Just kind of jokingly wagging my finger.”

The finger wag secured King’s stance as an advocate for anti-doping, an aspect of King’s legacy.

“It’s like having a stance on crime being bad. It shouldn’t necessarily be an issue, but it is. I’m glad that I am a spokesperson because I’m not afraid to speak my mind. I’m not afraid to share my opinion, and if you come after me, great, but I’m in the right.”

Marsh said King’s finger wag was not just a key moment at the Olympics but a call to other athletes to follow in King’s footsteps.

“If a sport is going to be clean, the athletes have to keep pounding the table,” Marsh said.

King has since gone on to become a major voice in pushing for clean sport. She traveled in 2018 to Washington, D.C. to speak to the World Anti-Doping Association.

Because of King’s finger wag, a rivalry was born. When King walked out for the gold medal race, the crowd cheered for her, while showering boos down on Efimova.

Despite Efimova winning her semifinal heat, Marsh said that she didn’t do anything impressive in her swim.

“That’s when I sort of had a smile on my face knowing that Lilly would, the night of the finals, would bring out her best and would be the kind of person that would rise to the big occasion,” Marsh said.

It was the race King had been dreaming of for years, but she treated it like just another meet. She had to.

“It’s different than it is watching from home because you never hear the NBC theme,” King said. “That’s what you associate with the Olympics. You don’t hear that at the Olympics because it’s only on TV.”

King, as always, was confident going in. Her parents weren’t nervous. Looze was.

“I had this recurring nightmare of Lilly just getting passed at the end,” Looze said. “Of leading it, leading it, leading it, and just getting passed right at the end. And I was just like, ‘How do I prevent this? How do we prepare for this?’ Everybody was like, ‘That’s not a nightmare, that could actually happen.’”

It nearly did.

King jumped out to the lead and touched the wall first at the 50 meter mark, with Efimova near the middle of the pack. As Looze feared, Efimova charged down the final 50 meters, inching closer and closer to King until they were virtually neck and neck.

In the final 15 meters, King found one last burst, pushing just ahead of Efimova and touching the wall first to win the gold.

King slammed her hands into the water in celebration, a beaming smile stretching across her face.

“It was amazing,” Looze said. “When all that happened, the pressure, it was like either you win or you just got egg on your face. Everybody would have had egg on their face.”

King stood atop the podium as the gold medal was placed around her neck, the Star Spangled Banner beginning to play.

“Anytime I’d hear the national anthem at a swim meet, I would think of myself standing on the podium, watching my flag go up,” King said. “Then we got there. I just remember I got my medal, I saw my mom in the stands, and I just looked at it and was like, ‘Wow.’”

King had accomplished her goal, she had won a gold medal. King went on to also win gold in the 4x100 relay. In 2017, she set the world record in the 100 breaststroke.

She’d accomplished everything she could in her best event. When she came back to Bloomington, she was bored. King said when there isn’t someone for her to legitimately race, she doesn’t want to be at the meet.

By now, King wasn’t racing others. She was racing against her own best times.

King’s illustrious college career saw her break her own American records over and over.

At the 2019 Big Ten Women’s Swimming and Diving Championships, King became the first woman to swim the 100-yard breaststroke in under 56 seconds. A month later, at the NCAA Women’s Swimming and Diving Championships, King broke her own record again.

This year, King’s Hoosiers won the Big Ten title in their home pool. The Big Ten crown was the first team title King had ever won on any level.

In Texas, King completed her collegiate swimming career. As she departs the IU team, she’ll leave an unmatched legacy not just with IU, but in the state of Indiana as a whole.

When looking at King’s legacy as a Hoosier, there isn’t anywhere else to start but her times and accomplishments.

In her four years at IU, King won two Olympic gold medals, set a world record and won eight national championships. Her eight breaststroke national titles are the most NCAA history.

On her Senior Day in February, the IU swim and dive team unveiled a banner of King, immortalizing her in the Counsilman Billingsley Aquatic Center. Her banner sits among other IU legends including Mark Spitz and Doc Counsilman.

King’s dominance was the key role in IU’s development from one of the weakest breaststroke groups in the nation to one of the strongest.

The IU women’s swimming and diving team has enjoyed its best run of success in program history during King’s tenure. With King, IU has finished in the top 10 at the NCAA four years in a row, a first in program history.

It’s a level of success that has drastically helped Looze in recruiting.

“I think she’s given us a chance to eventually win a national title here,” Looze said. “She’s really put us on the map as a destination place for women’s swimming.”

What King has done throughout her IU career has heavily influenced swimming in Indiana. Baumeyer said that he’s seen high school swimming participation go up in the state as kids are seeing what King has done at a collegiate and international level.

No town has felt King’s influence more than Evansville.

When King went home, she didn’t want to swim in the dilapidated Lloyd Pool. She didn’t want young swimmers to have to same experience she had growing up.

King, along with young swimmers and parents, went to a city council meeting in 2018 to push for a new pool in Evansville. King got her wish.

“I remember they announced that it was approved, my mom and I, we just looked at each other, we were tearing up,” King said. “The kids are going to have a locker. I never had a locker growing up. Isn’t that crazy? That’s nuts. Just knowing they’re going to have somewhere nice to train. They’re not going to have worry about if the pool is closed because it has imploded, because that those were things I’d have to worry about.”

King won’t be going far after graduating. She’ll stay in Bloomington and train with IU’s professional group. With the 2020 Olympic games in Tokyo on the horizon, King will be preparing to become the first woman to win two consecutive gold medals in the 100 breaststroke.

King hopes to win four total golds in Tokyo. The 2024 Olympics are already in King’s plans as well.

“To me it isn’t really an ending,” Looze said at the 2019 NCAA championships. “It’s just a really fantastic college career. Best of any breaststroker, maybe male or female, ever.”

Once her swimming career comes to an end, King doesn’t know exactly what she wants to do, but she has an idea: teaching.

King has been student teaching during the spring semester, finding a love for it. She’d like to become a teacher down the road.

While her legacy at IU may be set, her legacy as a swimmer is far from complete. IU has never had a female swimmer achieve as much as King has. According to Looze, no female athlete ever at IU can match King.

“If there’s a better female athlete at Indiana University, I’d like to know,” Looze said. “I think she’s the finest women’s athlete we’ve ever had here, and by a long shot.”