About a year ago, someone sent a link to 26 people through my Facebook Messenger account.

“Hacked?” one of my friends replied.

At the time, I changed my password, updated my privacy settings and shrugged off the issue. In a world where I’ve lost track of my online accounts, these breaches seem almost inevitable.

For the longest time, these issues didn’t seem real to me.

But after listening to podcast episodes that tracked down hackers of Uber and Snapchat accounts, I put my email address into “Have I been Pwned,” a website that searches across multiple data breaches to see if your email has been compromised.

Two data breaches stared back at me. Strangely, it wasn’t the fear of financial loss or identity theft that worried me the most. Instead, it was the revelation of how little I knew about my own privacy and security that made this begin to feel real.

Getting hacked is not uncommon. A 2017 Pew survey found that 64% of Americans have experienced a major data breach. The same survey found that about half of Americans do not trust social media sites or the federal government to protect their data.

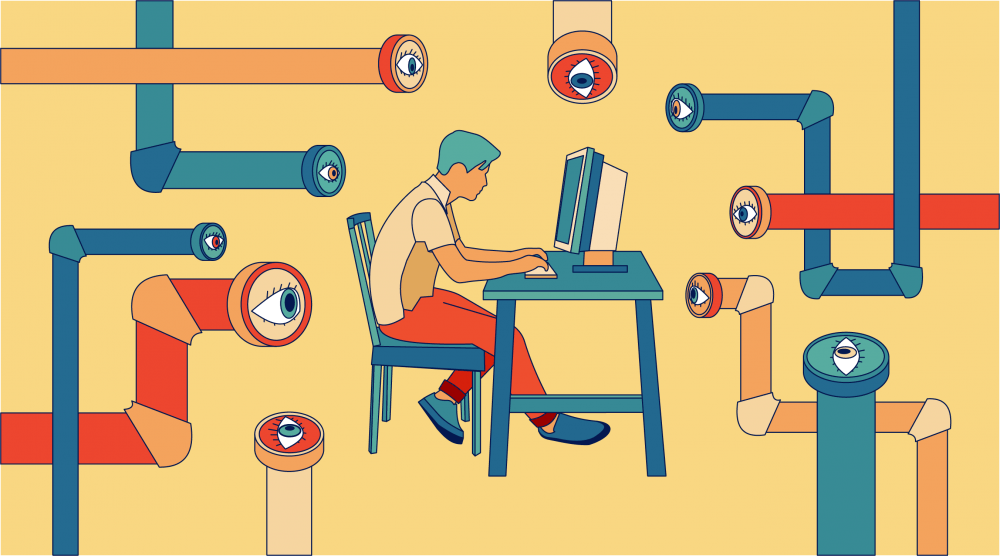

How do we operate in a society where vulnerability is becoming the norm? Most people trust that they won’t be targeted because they aren’t important, reflecting a mentality where they believe they can hide in the crowd.

This is an increasingly dangerous misconception. “The feeling that people can just hide in the masses is an outdated concept,” chief data officer for IU Sara Chambers said.

There are sophisticated ways of compromising our security and privacy online, and it’s our responsibility to be informed and take action.

Most people know they shouldn’t share sensitive information, like their Social Security number, online. But seemingly innocuous personal data can be used to make disturbingly accurate inferences about your identity.

Even if you don’t share your information, companies can use the data they have from other people to make inferences about your identity. This ability to deduce more about you than you disclose is known as “computational inference.” Companies can now predict, with high accuracy, information about you that you have never shared, including your religious beliefs, political views, sexual orientation and health.

“Organizations are building their version of your profile, which can include information about all aspects of your life,” Chambers said. “Decisions may be made based on these profiles without your knowledge.” This encompasses information about recent purchases, relationships, phone records, location information and more.

The implications are of great concern and can affect people’s lives beyond identity theft, such as in health.

A recent paper in JAMA Network Open found that out of 36 health apps studied, 33 transmitted data to a third party, which sometimes included sensitive information about substance use and mental health. A Wall Street Journal investigation found that the menstrual tracking app Flo shared information about period dates and pregnancy plans with Facebook. Privacy clearly goes beyond bank accounts and social media.

A common mistake that enables this kind of profiling is oversharing information.

“Oversharing seems innocent and safe in isolation, but organizations are collecting massive amounts of personal information from a variety of sources,” Chambers said. “When it comes together, it can paint a picture the student didn’t realize was possible.”

Andrew Kim, a junior studying computer science, agreed that oversharing is a common mistake among students.

“Once something is out there, it’s out there forever,” Kim said.

Maybe, like me, you find it hard to conceptualize these issues.

When I go outside in the winter without a coat, I feel cold. But when I share my information on the internet, I don’t know when I should feel exposed. There is a lack of a feedback mechanism when it comes to internet privacy. In other words, there’s no “cold” feeling to tell me when to put on a coat and protect my information.

Security also feels abstract to me. A deadbolt makes sense, but two-factor authentication can seem like a barrier. When I forget my phone at home, two-factor authentication feels like it’s locking me out instead of locking out potential wrongdoers.

Nevertheless, we lock the doors of our homes. Shouldn’t we do the same for our tech? After all, there are simple, effective ways to maintain our privacy and security online.

To protect obviously sensitive personal information, Chambers advises students to implement security practices, including two-factor authentication and password management.

Kim also emphasizes good password management.

“A common mistake is reusing passwords between accounts," Kim said. "This is often convenient, but it also leaves users vulnerable to credential stuffing.”

But if you’re like me, you have so many accounts that it’s hard to keep track of them. To resolve this issue, Chambers said that University Information Technology Services recommends using a passphrase vault, such as 1Password or LastPass, which locks different passwords behind a single, strong passphrase.

“Everyone in general should watch out for email phishing attacks, where a sender imitates a legitimate source and asks the receiver to send them their username and password. Even relatively technical people continue to fall for it,” Kim said. “Fortunately, common sense and a little Googling is usually enough to protect you from this.”

IU provides free phishing education and training to spot these scams.

To avoid less-obvious data sharing that leads to profile building, Chambers said that “if it’s not required, don’t share it.”

Instead of skipping those privacy notices, take the time to see what data companies are collecting and sharing with others.

“Privacy notices are now being written so they are more easily read, but students need to think about what they are reading,” Chambers said. “What control do you have over your data and how long will they keep your data?”

Finally, use common sense. “Protecting yourself online often comes down to good decision making. Technical protection alone isn’t a miracle worker,” Kim said.

We live in a society where online security and privacy feel increasingly scarce and where the burden of privacy and security often falls on the user, not the company.

We cannot be silent on this issue. Fortunately, times may be changing.

The Federal Trade Commission has been investigating Facebook for privacy violations that could lead to a multi-billion dollar fine. The New York Times is currently running a series of opinion articles on privacy. In the future, we need to continue these conversations and hold organizations accountable for our privacy and security.

“We haven’t made the leap to understanding how our data are being used behind the scenes,” Chambers said. “We need to become more aware as a society.”

These realities are not meant to scare people off the internet. Instead, they reveal our need for an informed public that holds organizations accountable for the data they collect and how they share it.