By Susanne Rust

Los Angeles Times

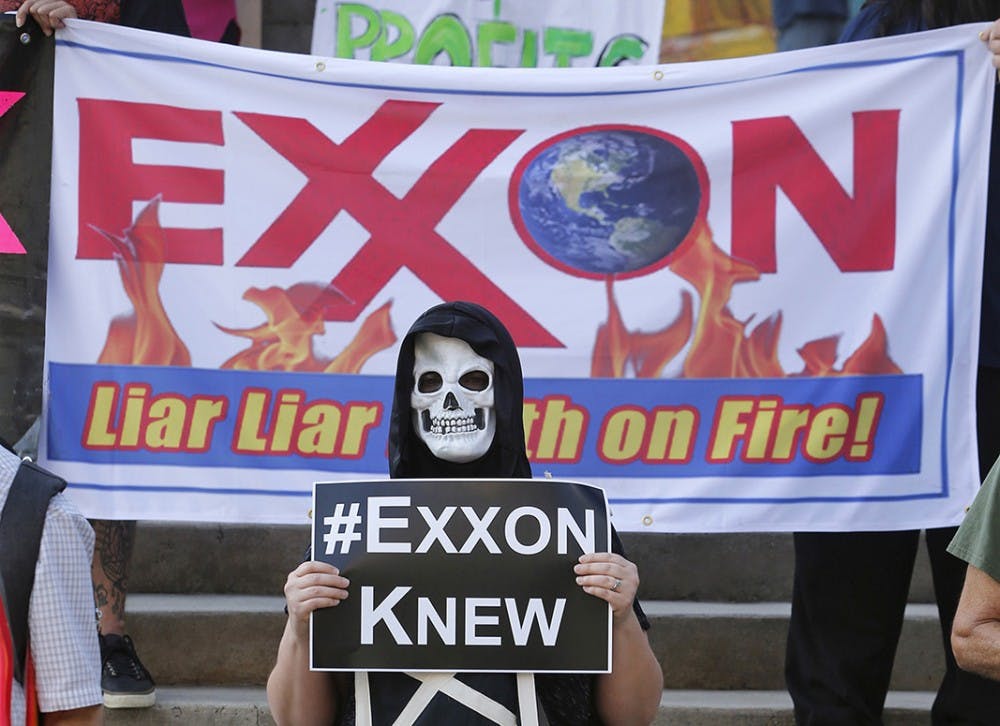

Two days before ExxonMobil goes to court Wednesday, facing New York state accusations the oil company misled investors about climate change, a team of researchers released a report Monday outlining the company and the broader fossil fuel industry's decadeslong campaign of deception, and its success at confusing the American public.

The report, which was published by scientists at Harvard, George Mason and Bristol universities, draws parallels between the campaigns launched by tobacco companies and oil industries to mislead the public about their products, both with a goal of delaying government policies and regulations that could cut into their profits.

Revelations about ExxonMobil's campaign came from 2015 news reports in the Los Angeles Times and Inside Climate News, and studies previous to Monday's have documented its efforts to manipulate public opinion.

ExxonMobil has previously dismissed such research as the work of anti-oil activists. But on Wednesday, New York's lawsuit, alleging the company mislead investors, is set to go to trial in state Supreme Court in Manhattan.

"For 60 years, the fossil fuel industry has known about the potential global warming dangers of their products. But instead of warning the public or doing something about it, they turned around and orchestrated a massive campaign of denial and delay designed to protect profits," said Geoffrey Supan, a researcher in the department of the history of science at Harvard. "The evidence is incontrovertible: Exxon misled the public."

The authors highlight the tactics used by the campaigns, including trotting out fake experts, promoting conspiracy theories and cherry-picking evidence. And they point to specific examples employed by ExxonMobil, including a 2004 New York Times advertisement that read like an editorial. It employed traditional disinformation techniques such as questioning scientific consensus and advocating for a "balanced" scientific approach to climate change, giving weight to those skeptical of the prevailing research.

The report suggests that while the disinformation campaign was successful in confusing the public and slowing a government response to a danger oil company scientists had identified as far back as the 1970s, such campaigns can be stopped.

Educating the public about the techniques used by these campaigns can "neutralize and inoculate the public against disinformation," said John Cook, an assistant professor of communications at George Mason University and lead author of the report.

Recent polls show a growing number of Americans believe climate change is occurring and that it is the result of human activity.

On Oct. 10, Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healy sent a notice to ExxonMobil of her office's intent to sue in civil court — for violating the state's Consumer Protection Act — "by engaging in unfair or deceptive acts" regarding the sale and branding of fossil fuel products.

ExxonMobil's lawyers are crying foul and have asked the Superior Court of Massachusetts' Suffolk County to slow down Healy's team — at least until the New York trial has come to an end.

"It appears your office has decided to charge the company without any consideration or concern for the underlying facts," wrote ExxonMobil's counsel, Theodore V. Wells Jr., in a letter dated Oct. 14. Instead, Wells said, the lawsuit seems purposefully timed to interfere with the New York trial.

"The timing of your notice provides further cause for concern that improper motives animate your office's decision to file suit," he wrote, suggesting it provided "the freshest evidence of your office's participation in a conspiracy with other state attorneys general."

Scott Silvestri, a spokesman for the company, said the New York and Massachusetts lawsuits were "... politically motivated and resulted from a coordinated effort by anti-fossil fuel groups and contingency-fee lawyers involved in other lawsuits against industry."

He added that "ExxonMobil believes that climate change risks warrant action and it's going to take all of us — business, governments and consumers — to make meaningful progress."