Bloomington’s natural resources manager didn’t set a goal for how many deer hunters should kill during the city’s first regulated cull over the past three weekends at Griffy Lake Nature Preserve.

Steve Cotter said the deer population is unknown, so it’s impossible to determine how many should die. But according to ecologists and deer management experts, there are too many deer for a healthy plant community.

City officials have attempted over the past decade to solve Bloomington’s deer overpopulation problem. A $25,000 grant from the Indiana Department of Natural Resources' Community Hunting Access Program allowed the city to hire a coordinator this year to organize a regulated deer hunt.

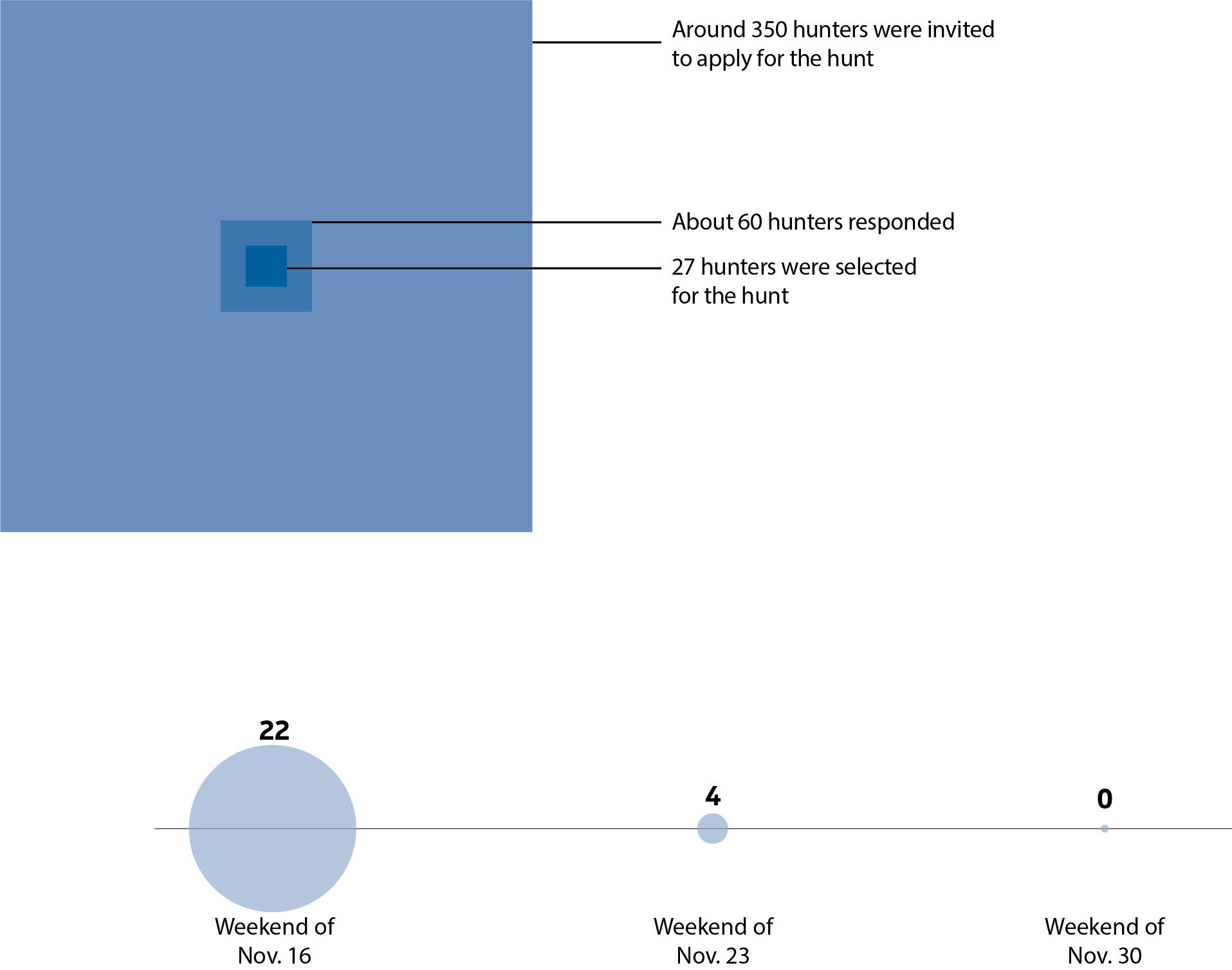

The 27 hunters were vetted and tested. CHAP hunts are supposed to benefit them, too, by providing an opportunity for recreational deer hunting.

The first weekend, hunters killed 22 deer. The second weekend, they killed four. The final weekend they didn’t kill any.

A healthy ecosystem should have about 15 deer per square mile, Cotter said. For an ecosystem as damaged as Griffy Lake, there should only be about five per square mile. That means just 10 deer should roam the 2-square-mile preserve.

“For a first attempt, I think it went pretty well,” he said. “We learned a lot.”

Killing deer used to be more controversial.

City and county governments have explored deer management since September 2010, when the Joint City of Bloomington-Monroe County Deer Task Force began its work.

Then-mayor Mark Kruzan blocked 2014 legislation that would have allowed professional sharpshooters at Griffy Lake. City council overturned the veto. Protesters wearing deer masks congregated outside City Hall. No deer were killed.

In 2017, the city spent about $43,500 to hire a sharpshooter from White Buffalo Inc., a deer management company, according to a 2018 Bloomington City Council meeting. The shooter killed 62 deer.

Then in 2018, the city received a grant from DNR’s CHAP program that would fund a coordinator for a community deer hunt for up to $25,000 a year for two years. This program is more cost-effective because hunters purchase their own licenses and equipment, said Sam Whiteleather, a wildlife biologist with the DNR.

It also creates hunting opportunities for Indiana residents.

“There’s more demand than there are places to hunt,” Whiteleather said.

But by the time the city council approved using firearms at Griffy Lake for the hunt in 2018, it was too late to recruit enough hunters. The Parks and Recreation Department postponed the hunt until 2019.

Cotter knew of just three complaints throughout the 2019 hunt. One person visited the preserve to express concerns. Another called him.

“I think the increasing number of deer in neighborhoods in Bloomington helped people understand the threat that they pose to the nature preserve,” Cotter said.

Four community activists co-wrote a guest column in the Herald-Times last week calling the hunt “the latest in a series of costly, misguided assaults on the Griffy deer who are said to be denuding the park.”

The activists, including city council member Dorothy Granger and two employees for the Humane Society of the United States, pressed for using nonlethal alternatives such as fertility control programs.

“It’s an embarrassing record of mismanagement, but that is because the city’s aim is misguided,” the column said. “At a time when climate change and accelerating species loss threaten the very future of our planet, the city needs to practice coexistence with the wildlife who share our parks and yards.”

Robert Rudisill, a CHAP coordinator from Boonville, Indiana, has hunted deer for 52 years. He said he loves the “thrill of the chase.”

“I love being out in God’s tabernacle,” he said.

Rudisill was one of about 350 hunters invited to apply for the Bloomington hunt, and one of about 60 who responded. He answered personal questions about his educational background and willingness to hunt antlerless deer, and he provided three references.

After passing the application, Rudisill completed a proficiency test, hitting three consecutive shots in a four-inch circle from 50 yards away.

Twenty-seven hunters qualified, Bloomington CHAP coordinator Ryan Rodts said.

Rodts and Cotter said they wanted more.

Before the hunt began Nov. 16, Rudisill scouted the area. He noticed a lot of tracks and droppings. He killed three deer in two hours.

Then he brought the deer home and deboned the meat, which took about an hour per deer. On Black Friday each year, Rudisill, his son and his son’s friend come over and make jerky with the meat.

Hunters could choose to donate their meat to Hoosier Hills Food Bank, but Cotter said every hunter kept the deer they shot.

Kevin Tungesvick, a senior ecologist for Eco Logic LLC, measures plant heights in early May at the preserve to study the effects of deer browsing. After the 2017 sharpshooter killed 62 deer, Tungesvick said he noted “minor improvements in height and browse activity.”

But after the deer were left alone in 2018, his measurements returned to 2016 levels. He said he doesn’t expect to see a major improvement until three to five consecutive years of deer removal.

“Deer management will always be a part of the park,” he said.

Cotter said he expects to use the CHAP grant to repeat the hunt next year, but he isn’t certain. The city could also pursue a deer reduction zone designation, which would allow individual hunters to kill more deer during the deer hunting season. Or they could hire another sharpshooter.

Uncontrollable factors likely affected this year’s outcome.

Rodts said rain and cold the second and third weekends probably deterred hunters who planned to participate. And the state reduced Monroe County’s deer harvest quota from five to three deer this year because of an outbreak of a deer disease called Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease.

Once a hunter shot two antlerless and one antlered deer, they had to stop.

Rodts said hunters told him they saw many more deer than the 26 they were able to shoot.

“I would’ve liked to harvest more deer,” Rodts said. “There’s no question about that.”