Yes! magazine released an article in December describing a tribal elder hearing his grandfather's voice for the first time due to IU researchers’ digitally preserving thousands of Native American songs on wax cylinders. However, not everyone is pleased about using modern technology to preserve these songs.

Some western academics and Native groups do not think these recordings should be made available to the public due to the sacred nature of the culture they come from. Rather, they believe these recordings should only be heard by the groups for which they were intended.

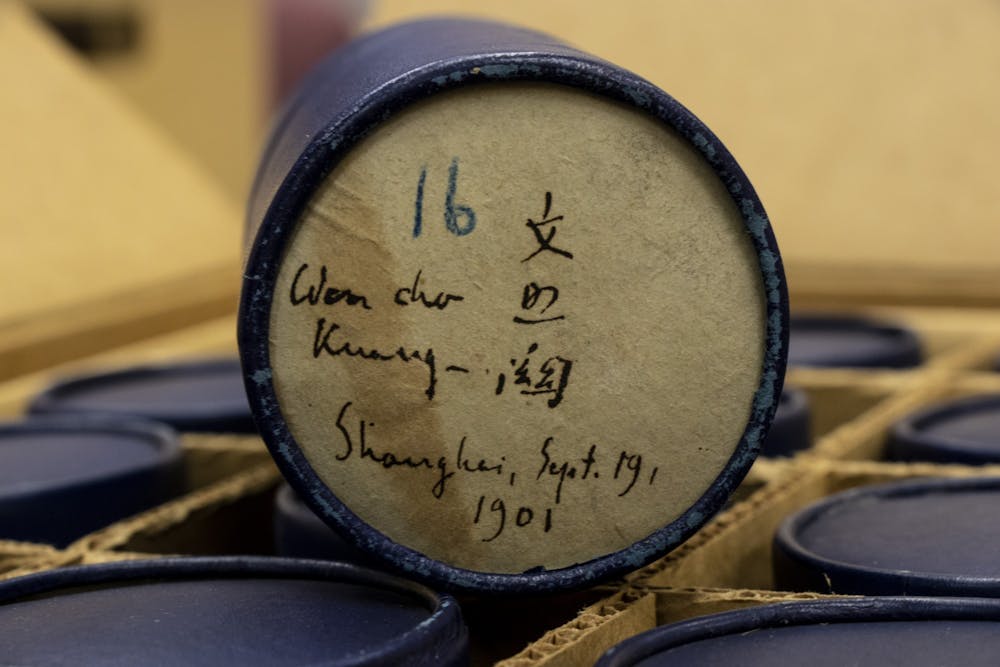

Daniel Figurelli, senior audio preservation engineer for the Media Digitization and Preservation Initiative, said the initiative has 7,000 cylinders, each containing recordings from more than 60 countries, the majority of songs from Native groups in North America.

The goal of the project is to allow people access to these media collections online, Figurelli said.

The family members and communities to whom these recordings belong must agree to give IU the rights and usages of the recordings for them to be put online, Figurelli said. The MDPI is meant to present this material for educational and research purposes, not commercialize it.

In an email to the Indiana Daily Student, Renson Madarang, the Native education and programs assistant for the First Nations Educational and Cultural Center said it is great to see researchers using technology to preserve these cylinders. He said the cylinders may have been lost to time or damaged without preservation.

“There is a lot of potential for good to come of preservation projects, especially when it is done in collaboration with the appropriate indigenous communities,” Madarang said in the email.

However, Madarang said it’s important for researchers to identify and respect the host cultures from which IU has received these pieces and allow them the opportunity to decide how these artifacts are preserved and made available for the masses.

Although these are historical recordings, not all of the songs are lost or no longer sung, Madarang said in the email.

As an academic of indigenous heritage, Madarang said he can understand the value of cultural preservation, but these recordings belong to a living community and culture.

“It is up to the inheritors of these traditions to determine the depth of Western academia’s involvement in the perpetuation of said culture,” Madarang said.

Nicky Belle, director of the FNECC, said the digital preservation of these wax cylinders is one example of how modern technology can be used to support cultural transmission.

The piece that is in question is who should have access to these materials, Belle said. He said there is a lot of material in the collections, and as the FNECC learns more about what is in the archives, the center will pass that information to tribal representatives and communities so those groups will have the opportunity to come and listen.

Belle said there are mixed opinions among the Native American community about this project of digitization. He said some recordings are public, while others are specifically meant to be heard by certain people or at specific times of day. There are some people who say these songs should never have been collected.

Belle said some tribal groups have recordings that are only meant for women or men. These specifications vary from group to group, making opinions on digital preservation differ in the Native American community, he said.

Jayne-Leigh Thomas, director of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, said it is important to have open and transparent conversations with tribal communities about these recordings. She said her office has been working with the Archives of Traditional Music at the IU Libraries to make sure tribal communities are aware of this project and help the communities access the songs.