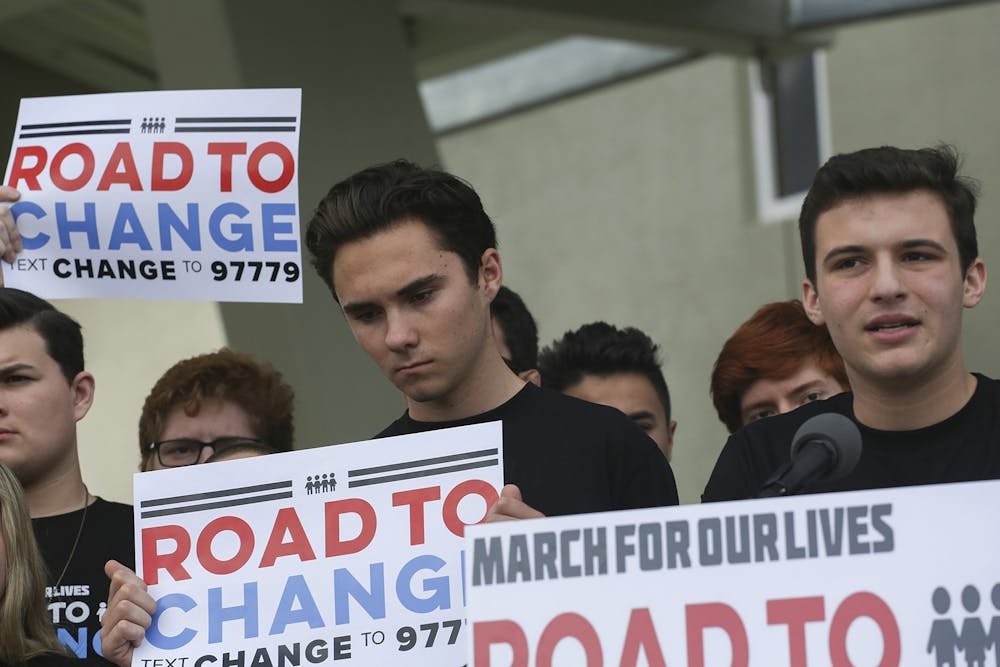

Valentine’s Day marked the second anniversary of the Parkland school shooting, in which 17 students and teachers were killed. Survivors created an organization following the shooting called March for Our Lives, which organized a national school walkout and a subsequent rally on March 24, 2018 in Washington, D.C.

March for Our Lives has raised awareness and mobilized young people, and it was arguably a principal cause of the decline in support for the NRA. However, it has become more of an advocacy organization than a protest movement, and due to this change it has had few if any legislative successes. If gun control activists care about legislative change, they should organize more like the sustained, disruptive and enduring protests of the 1960s.

Mainstream advocacy groups can be incredibly useful, but persistent boycotts, strikes, walkouts, sit-ins and other forms of disruptiveness and combativeness are the most useful tools available to disenfranchised groups like the minors who suffer from school shootings.

March for Our Lives has done commendable and crucially important work, and there have been more direct actions since the initial walkouts and rallies. Just last week, students occupied Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s office to demand he pass the gun legislation that has been passed by the House. It has inspired and lobbied for such legislation, notably the Bipartisan Background Checks Act of 2019.

That sort of action should have been happening all along, rather than every anniversary. March for Our Lives should have maintained the momentum that launched the movement.

I was about four months from graduating high school when the Parkland shooting happened and March for Our Lives was born. A group of my peers and I organized a school walkout and a trip to Washington, D.C., for the national rally.

My experience in the walkout was completely different from my experience in the rally. The walkout was fundamentally student-driven and fundamentally a protest. The focus was student voices and experiences, with community leaders and activists supporting rather than superseding us.

The rally, on the other hand, was a commercialized affair. The student speakers were inspiring, as was the turnout of about 800,000 people in D.C. It changed the terms and gravity of the debate around gun violence, but it did not feel like a student-led protest movement. It felt like a concert, which contradicted the grassroots character of the March for Our Lives.

Waiting for the next celebrity act to come on stage felt like a waste of political capital and momentum and a distraction from the purpose and aims of March for Our Lives, which in turn undermined further grassroots action. A protest movement that wanted to remain a protest movement would have capitalized on the mobilized rage present that day and seized an opportunity to launch more disruptive, effective direct action campaigns for the future and encouraged mobilization for next steps besides voting.

I went to D.C. excited and hopeful, but after I came home and the glow wore off, I realized that I had expected more. I had expected a sustained campaign, but the March for Our Lives is no longer primarily a protest movement, even though it was born as one.

As a participant and a supporter, I applaud its organizers and its successes. But March for Our Lives chose to stop being a protest movement and to redirect to town halls and forums, which strikes me as mistaken and far easier to ignore than direct action.

If the goals of March for Our Lives are to be met, gun violence activists have to do more than ask nicely within established channels of dissent, and they have to regain the momentum they had in March of 2018.

Kaitlyn Radde (she/her) is a sophomore studying political science. She plans to pursue a career in public interest law.