Monroe County government filed a lawsuit against the United States Forest Service along with other plaintiffs last month in U.S. District Court in New Albany, Indiana, according to a press release from the Office of Monroe County Commissioners.

The lawsuit was over the Forest Service’s plan to log, burn and apply herbicides to a significant portion of the Hoosier National Forest, which has been facing opposition since the end of 2018.

The Indiana Forest Alliance (IFA), the Hoosier Environmental Council and plant biochemist David Simcox joined the county government in filing the May 13 lawsuit.

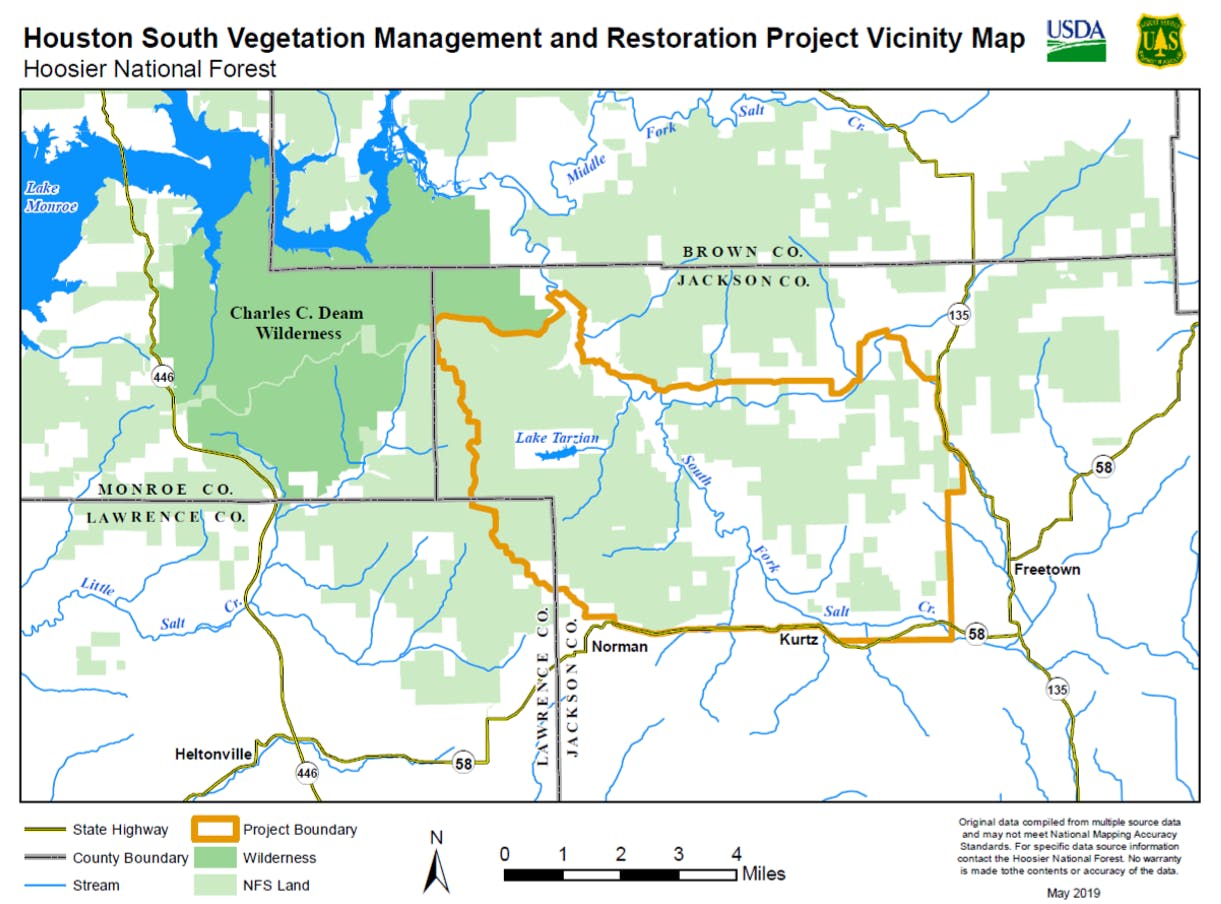

The plan, the Houston South Vegetation Management and Restoration Project, could take up to 20 years and includes 13,500 acres of prescribed burning and 4,375 acres of tree thinning, clear cutting and harvesting, according to the Forest Service's environmental assessment of the project. The project was approved by the Forest Service on Feb. 14 despite objections from experts and community members.

The stated purpose of the project, according to the assessment, is to “promote tree growth, reduce insect and disease levels and move the landscape toward desired conditions.”

The project takes place mostly in Jackson County and the rest in Lawrence County. However, the project’s proposed logging and burning areas overlap with a portion of the watershed of Lake Monroe, the sole source of drinking water for 140,000 people in the Bloomington region, according to the press release citing Monroe County Commissioner Julie Thomas.

The project will potentially yield soil and nutrient runoff that may pollute Lake Monroe.

Steep slopes exist in the project area, which encourage greater sediment and nutrient runoff than flatter surfaces, according to the assessment.

The assessment states that incorporating best management practices for water pollution could mitigate the potential pollution. However, Tim Maloney, senior policy director at the Hoosier Environmental Council, said such practices aren’t always successful and the Forest Service doesn’t have enough resources to monitor and maintain them.

Soil and nutrient run-off can lead to eutrophication in water bodies, favoring algae growth and killing other species by depleting them of oxygen. Due to pollution and sedimentation from decades of agricultural activities, the Indiana Department of Environmental Management has already listed Lake Monroe as impaired water, citing algae blooms and odors.

“Compared to what’s coming off those agricultural fields, this will have no impact at all,” said David LeBlanc, professor of biology at Ball State University. He said he has helped the IFA conduct fieldwork in the past, but he disagrees with their position on the Houston South Project.

However, to Jeff Stant, executive director of the IFA, the project would be like adding fuel to the flame.

“The problem here is that they are making a stressed situation worse,” he said.

Vic Kelson, director of City of Bloomington Utilities, which ensures clean drinking water for the city, declined an interview request, saying the department will reserve its comments for inquiries from parties of the pending litigation.

The project may also bring harm to the habitats of endangered bat species and other wildlife, exacerbate impacts from climate change through logging and burning and damage recreational trails, according to the lawsuit.

Stant said by trying to promote the Hoosier National Forest’s oak-hickory system, the Forest Service is essentially preparing the types of trees most profitable as commercial timber.

“Because these guys are fundamentally loggers, they want the forest to be used, including public forests,” Stant said.

LeBlanc said, however, that the Forest Service is perfectly justified to do so.

“This is a part of the forest that has been designated as potentially providing timber production,” he said, citing the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960 that allows national forests’ renewable surface resources to be managed by the federal government to meet the country’s needs.

The groups filing the lawsuit were frustrated about the failure of the Forest Service to address objections and consider alternative locations for the project.

Monroe County Attorney Margie Rice attended the last meeting early this year between the Forest Service and objectors to the project. She said the Forest Service did not address their objections.

“Sitting on the side listening to the United States Forest Service talk to the objectors around the table, there were no answers to the questions,” she said. “They were basically just saying, ‘Please withdraw your objections. What can we do to get you to withdraw them? We’re not changing our plans.’”

“They were intent on proceeding with the project and had the framework of the project in mind,” Maloney said. “And they have really not varied from their original intent in any substantive manner.”

The Forest Service did formally respond in writing to comments of objection and publish them online, but it practically proposed no modification to the original environmental assessment.

The final environmental assessment and the Finding of No Significant Impact both claimed the Houston South Project would not have a significant impact on the environment.

A FONSI shows that an agency’s proposed action does not bring significant impact to the environment. The National Environmental Policy Act requires that an agency prepares a FONSI to be exempt from preparing an Environmental Impact Statement, which would need to address the direct, indirect and cumulative environmental impacts of the proposed action.

NEPA also requires that the agency in its environmental assessment briefly discusses alternatives to the proposed action and their environmental impacts.

“Many members of the public, including the plaintiffs in this litigation, provided specific alternatives that would better protect the environment, but the Forest Service refused to consider any alternatives other than either doing nothing at all or doing exactly what it proposed to do,” said attorney Nick Lawton, a senior associate at Eubanks & Associates, the law firm representing the plaintiffs.

Lawton said the alternatives proposed included locating the project outside the Lake Monroe watershed or, if in the watershed, plans that would better protect the environment.

One of the alternatives was relocating the project to a 63,000-acre area in the Hoosier National Forest that does not carry the risk of polluting reservoirs. This area is much larger than the proposed acreage covered by the Houston South Project.

Simcox, one plaintiff of the lawsuit, said because relevant records have not been disclosed to the public, he didn’t know the thoroughness of the Forest Service’s examination of the alternative locations. He said he asked the Forest Service multiple times whether they have examined rigorously the feasibility of conducting the forest management activities in that area, but he was told that it had been decided that the proposed location would be the best location.

Simcox holds a doctorate degree in plant biochemistry from University of California at Los Angeles. He is a member of the Monroe County Environmental Commission and a former volunteer board member of the IFA.

However, in this lawsuit, he files as an individual plaintiff as he had personally sent letters of comment and objections to the Forest Service and is concerned as a regular hiker at the Hoosier National Forest.

Stant said the Forest Service was only citing research to support the project and ignored studies suggesting otherwise.

“They’re acting in an arbitrary and capricious manner,” he said. “Federal law doesn’t allow them to do that. That’s what NEPA’s about – avoiding that way of operating.”

The lawsuit seeks to ask the court to send the project proposal back to the Forest Service for further analysis following NEPA requirements, according to the press release. Rice said the hope for this lawsuit is that the Forest Service would engage in meaningful dialogue with members of the public to help them understand the necessity of the project and why it does not bring the negative environmental impacts it is alleged of potentially bringing.

If they fail to convince the court to have the Forest Service re-review the project, Rice said that would mean the court has determined that the Forest Service has followed NEPA and other legal requirements and that the project can proceed.

Lawton said the lawsuit is likely to last six to nine months if expedited, or one to one-and-a-half years if not. He said he hopes to work with the government to put a hold on the Houston South Project before the court reaches a decision.

Currently, the case is at a very early stage, Lawton said, and the parties are collaborating on a schedule to brief the court on their positions.

The Forest Service declined to comment, citing pending litigation.