Recent years have seen many protests, from the Women’s March to climate marches. Most recently, in response to many high-profile police killings, a student-led Black Lives Matter protest in Bloomington drew thousands. Other actions followed. In short, IU student activism is nothing new.

Our rich protest history varies widely in tone, tactics and targets. Although 1960s activism is often remembered as something that happened on the coasts or in the Deep South, it happened all over the U.S., including right here in Bloomington. Here are three of the most memorable, so that you can keep your Hoosier dissident ancestors in mind the next time you plan or participate in a protest at IU.

1. The Green Feather Movement (March 1954)

In the mid-1950s, McCarthyism and the Red Scare had spread to every corner of America, including to IU. Due to fears about students and young people taking the wrong messages out of literature, some officials and textbook commissioners sought to ban all stories about Robin Hood and his merry men.

In a mocking protest, five students gathered chicken feathers from local farms and dyed them green in a bathtub, representing the green feathers that Robin Hood wore in the stories. They then spread the feathers all over campus.

This lighthearted protest caused outrage. A local newspaper, then the Bloomington Herald-Telephone, disparaged the five students who carried this out. The Indiana Daily Student had trouble getting professors to comment, since the students were under investigation by the FBI for their protest and they feared the same consequences if they expressed support.

They were not granted the status of an official student organization, but their defense of academic freedom and their interactions with administration and faculty influenced later student protests for years.

2. Dow Chemical Company Protest (October 1967)

IU students participated in the anti-Vietnam War movement, often by protesting IU’s connections to the war, such as faculty research supporting the war effort, compulsory ROTC, which student activists successfully ended, and recruitment by companies that manufactured military items. One such company was Dow Chemical Company, which manufactured napalm.

Anti-war students marched from Ballantine Hall to the business school and walked up to the interview rooms, demanding to see the Dow recruiters. When they refused, they quietly sat outside the interview rooms, holding signs for interviewees to see before they went in. One read: “Check your appearance. Are you responsible enough to be interviewed by the makers of jellied death?”

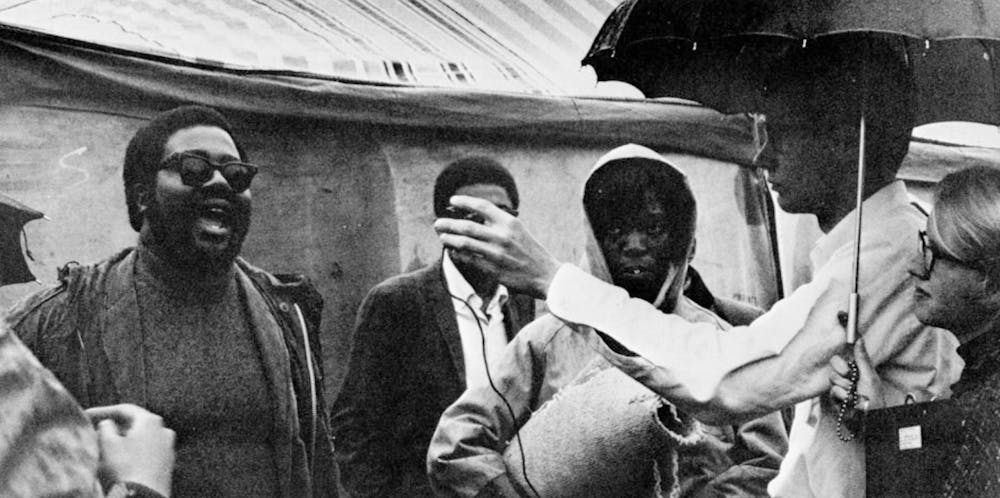

The police were called, and they arrested all of the participating students, some of whom went to the bus of their own accord. The police immediately began dragging the students who remained, beating them with newly issued riot sticks. One of the policemen ordered the others to “get the colored boy” in reference to Robert Johnson, the only Black participant in this particular protest.

This was the most violent police confrontation on IU’s campus. Evidence of brutality and racism in the police department made many students and some faculty uncomfortable with having police on campus, leading some of the students’ faculty allies to plead with the administration not to call the police in the future.

Some companies, and the CIA, cancelled IU recruiting visits. This protest caused more students to identify as actively anti-war, and it exposed the racism and excessive force inherent in the police.

3. Occupy Little 500 (May 1968)

The Little 500 is one of IU’s most famous and most lucrative traditions. In the late 1960s, there was no women’s race yet, and only white fraternities participated.

A group of 50 Black students decided to occupy the stadium and refuse to move until the fraternities struck the racially discriminatory clauses from their charters. The occupation lasted 38 hours, even after it began to rain and the stadium turned to mud. It was closely monitored by the FBI.

The students feared attacks from the Ku Klux Klan, which at this time frequently made itself known via acts of racial terror in Bloomington, and from law enforcement. But some faculty members came to show support, and fellow IU students and local high school students, Black and white, came to offer protection and supplies.

The race was postponed by a week due to the weather, and IU’s administration during this period ruled that no fraternity with discriminatory clauses would be allowed to race. Bloomington fraternity leaders frantically called their national offices to try to get rid of their clauses in time, and all but one succeeded and were allowed to race.

Note: All information, unless otherwise cited, comes from the book “Dissent in the Heartland: The Sixties at Indiana University” by Mary Ann Wynkoop.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story mistakenly referred to the Dow Chemical Company. The IDS regrets this error.

Kaitlyn Radde (she/her) is a rising junior studying political science.