Three years ago Wednesday, a young LGBTQ+ person, anti-fascist and president of the Pride Alliance at the Georgia Institute of Technology was having a mental health crisis. We would not know this, and Scout Schultz might still be alive, had police officers not approached Schultz outside a dormitory. In a matter of minutes, Georgia Tech police officer Tyler Beck shot and killed Schultz from a distance. Beck claimed the closed multipurpose tool in Schultz’s possession was a threat to the officer’s safety.

“I never felt safe at Georgia Tech after I learned that it has its own police force,” said Marissa Shields, a friend of Schultz. “While most students were, and still are, enamored with their social media stunts and ‘outreach’ efforts, they murdered my friend having a mental health crisis. Students have since pushed for reforms including crisis training and tasers, but we will never be safe as long as state-sanctioned executioners occupy the campus, with or without guns.”

Across the country, and in the wake of protests following George Floyd's death, students are demanding their universities dismantle university-affiliated police departments. It has become clear to many that the issues with policing are not a matter of “good” and “bad” cops, but of an institution that is fundamentally racist. It is an institution designed to suppress protest and unable to respond adequately to everyday problems such as domestic violence and mental health crises.

The history of American policing is defined by its origins in slave patrol, the oppression of minorities and the use of violence to in situations better served by de-escalation and access to basic resources.

Today, police killings of Black people occur nearly three times more often than police killings of white people. Meanwhile, a 2015 study by the Treatment Advocacy Center found 25% of people murdered by police had severe mental illness. Despite the fact that the vast majority of calls to campus police are for non-violent situations, and most so-called “violent” situations do not warrant force, 91% of public universities have armed officers.

Campus policing cannot escape the lineage of police violence in non-campus settings. A re-evaluation of campus policing — and the collaboration of campus police with city, county and state police departments — is long past due.

To better understand the origins and functions of campus policing, I spoke with Micol Seigel. She is a professor in American studies at IU and studies policing as a form of violence. The IU Police Department formed in 1971 and graduated its first class of police officers in 1972. University police departments, Seigel said, were founded in order to suppress antiwar and civil rights protests in the 1960s and 1970s on campuses across the country.

“Created amidst the student unrest of the antiwar and civil rights movements, campus police were supposed to be more attuned to the particular needs of a student community,” Seigel said in a statement. “Yet campus police have proven identical to their city counterparts, particularly in the treatment of students of color, labor struggles and protest.

Schultz’s friends at Georgia Tech became acutely aware of police repression of protests on campus when they confronted the Georgia Tech Police Department on the night of Schultz’s vigil and were attacked by law enforcement and charged with felonies.

Students and faculty in the University of California school system have also seen firsthand the ways police violence is leveraged against student protesters. In February of this year, graduate student workers at UC Santa Cruz declared a work stoppage to demand a Cost of Living Adjustment to their wages.

The police responded to students’ demands for a living wage with violence.

In the first week of the strike, the UC Santa Cruz administration spent $300,000 per day on policing, said Nick Mitchell, a professor in feminist studies and critical races and ethnic studies at UC Santa Cruz.

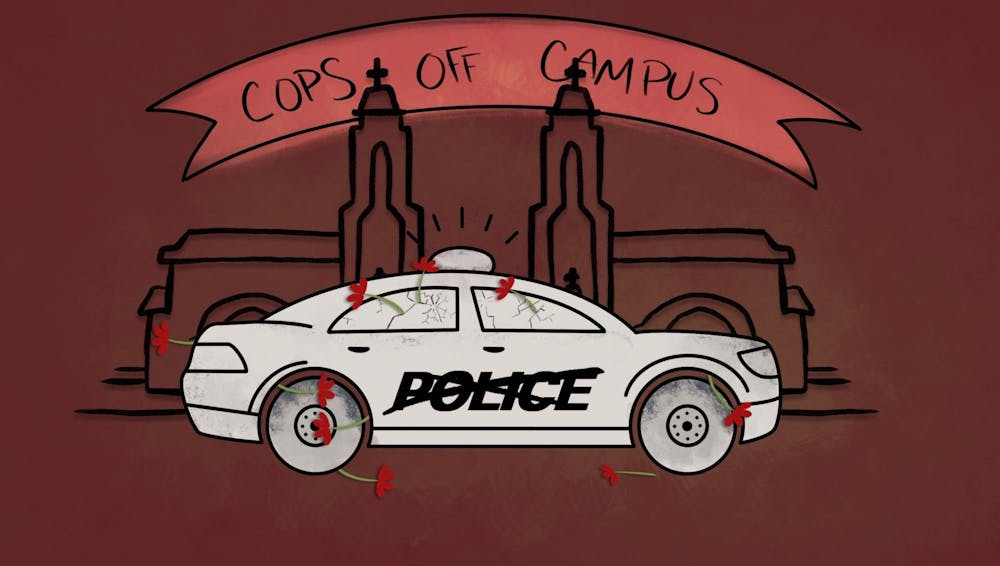

This experience with campus policing prompted students to form the Cops Off Campus campaign, which made police abolition its goal. Mitchell is also a faculty representative of the UC Santa Cruz Cops Off Campus campaign.

“What’s distinctive about our particular Cops Off Campus formation at UC is that it is a distinctly abolitionist one,” he said. “We aren’t simply calling for a reduction in the budget for policing. It’s not asking for better police, or kinder police, or Blacker or browner or queerer police."

In her Public Seminar piece titled “Reject Reform: Why ‘No Justice, No Peace; Prosecute Police’ hopes for too little,” Seigel argues against reform and prosecution of police as viable solutions to police violence.

“The police are the people who inflict the state of exception on those whom it deems unworthy of those rights," the 2020 article reads. "As things now stand in America, they get the deadly last word.”

What can IU students do to fight against police violence? Mitchell and Seigel urge students and faculty to demand cop-free campuses.

“In the wake of the police murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Tony McDade and others, the global struggle against policing was one that was urgent to fight on our own campuses,” Mitchell said. “Many of us had learned many times over that police function as the front line of defense for the various forms of inequality that universities enshrine.”

Directing his message to IU students in particular, Mitchell said students who are not on UC campuses should organize on campus, regionally and nationally. He urged students to study the police on their campuses and reach out to organizers at UC and elsewhere for support.

"Members of the IU-Bloomington community who genuinely hope to diminish the racism on our campus could find no better first step to take than to dismantle the IUPD and the cadet program,” Seigel said.

Bradi Heaberlin (they/them) is a second-year Ph.D. student studying geography and informatics. They are also a member of Young Democratic Socialists of America Bloomington and the Graduate Workers Coalition.