The 2020 election produced mixed results for both major parties. Republicans lost the presidency but are likely to continue controlling the Senate, though that will not be guaranteed until the Jan. 5 Georgia runoffs are finished. Meanwhile, Democrats retained an extremely slim House majority of 222 members.

The slim margins in the House and Senate are certain to result in unwanted outcomes for both parties at some point, but those same margins may also be wielded as a political tool. The majority parties will need nearly every vote from their coalition to pass legislation. Close margins mean that senators and representatives who are known to cross party lines will cast decisive votes. Moderates and progressives will now have the grounds to demand that their interests are considered in each bill in exchange for their coveted votes.

The dynamics of a narrowly split House of Representatives and perhaps evenly split Senate will give moderates and progressives the leverage they need to accomplish the policy goals their constituents demand of them, such as a balanced budget or climate change legislation. At the same time, this creates a conflict between the moderates and progressives, both of whom will be necessary to get basically any legislation passed. Narrow majorities for either Republicans or Democrats in both Houses of Congress will likely also magnify any intra-party conflicts.

Recently in the Senate, moderates have outsized power on important bills with strong opposition from the opposing party. For example, when the Senate rejected the “skinny repeal” of the Affordable Care Act in 2017, which would have eliminated the individual mandate and delayed the employer mandate while leaving the rest of the act in place, it was moderate Republican Sens. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, Susan Collins, R-Maine, and the late John McCain, R-AZ, who doomed the bill.

The House has much larger caucuses on both sides, so it is naturally easier to pass a bill without securing every single vote from the caucus. However, with only a slight majority, it will be nearly impossible for Democrats to pass any major legislation that Republicans ardently oppose without securing every Democratic vote, including the most progressive representatives. The next two years will prove to be a headache for both Republican and Democratic leaders as they contend with small majorities and potential dissidence from key members.

If Republicans maintain the Senate, Collins and Murkowski will often hold the deciding vote on legislation that sharply divides the Senate. If Democrats retake the Senate majority via victory in both Georgia runoff elections and a Democratic vice president, they will be forced to deal with the constraints that moderate senators such as Joe Manchin, D-WV, and Kyrsten Sinema, D-AZ, place on their agenda.

One item on the Democratic agenda that will be essentially impossible with a 50-50 split in the Senate is transforming the District of Columbia from a federal district into its own state. Statehood for Washington, D.C. has been on the progressive agenda for years. Manchin has explicitly stated his disagreement, citing a need to be further convinced on the issue, but leaving open the possibility of changing his position.

Sinema also proved her willingness to defy the Democratic party when she was one of only three Democrats to vote in the affirmative for Bill Barr’s confirmation as Attorney General, along with Manchin and soon-to-be former Alabama Sen. Doug Jones. Her votes on divisive issues, such as statehood for Washington, D.C., cannot be taken for granted by the Democratic party.

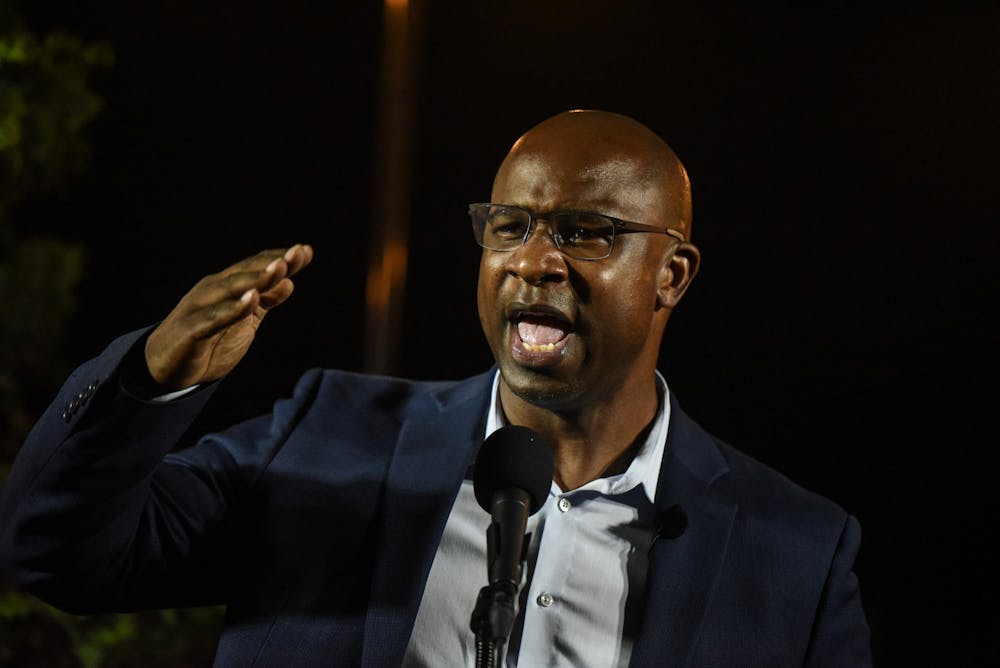

The House of Representatives is composed of many smaller informal groups, such as the Problem Solvers Caucus, the Freedom Caucus, and the Blue Dog Coalition. One informal group that has attracted notable public attention is the “Squad,” composed of Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-NY, Rashida Tlaib, D-MI, Ilhan Omar, D-MN, and Ayanna Pressley, D-MA.

These four congresswomen were all freshmen in the 116th Congress and were all reelected in 2020 by overwhelming margins to the 117th Congress. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has dismissed the “Squad” as only “four people”, but four votes could easily determine the fate of many bills this session.

Because the Biden-Harris administration ran on a message of national unity and President-elect Joe Biden is historically a centrist, it is likely that at least some of the legislation his administration will be pushing is not going to be as progressive as members of the Squad would like. Of course, this remains to be seen. There is a chance that Biden’s agenda will end up being more progressive than expected. For the House to pass meaningful legislation supported by Biden, though, Pelosi will need to either find some means of keeping the Squad in line or find some Republicans willing to cross party lines.

Republican cooperation with much of anything the Biden administration attempts to push through Congress will be at an all time low. This is not only due to the typically low bipartisanship between a minority party and a majority party who also controls the presidency, but also because of a disgruntled soon-to-be-former President Trump who will not likely be kind to Republicans who enable Biden’s agenda.

Leaders from both parties who have the support of rank-and-file members will spend plenty of time over the next two years wondering if a piece of legislation is too moderate for the progressives, or too progressive for the moderates. Either way, the 117th Congress is shaping up to be one of the most gridlocked yet.

Jack Rosswurm is a junior majoring in international studies and minoring in political science. He’s passionate about politics and adores the Star Wars franchise. He also loves learning about German language and culture.