The worries keep him up at night. He tosses in his bed. He paces around the house. Thoughts pinball through his mind.

Angel Escobedo thinks about his three children: Malachi, 4, Saniyah, 3, and Zoe, 1. He wanted them to be able to go to the pumpkin patch during Halloween. He wanted them to see their cousins at Christmas. But there’s a pandemic. He hopes they aren’t missing out.

The third-year IU wrestling coach worries about recruiting the right athletes to the program. He wants to bring a 2-10 team back into national relevancy. His inbox is constantly overwhelmed by emails and text messages. In September, the program was forced to pause workouts for two weeks after positive COVID-19 tests.

“It never stops,” Escobedo said.

Escobedo realizes there are some things he can't control. He tries to stay present and let the worries go. He’ll slip in his airpods while he's in bed and open the Headspace or Calm app on his phone.

Breathe, it tells him. In through the nose. Out through the mouth.

Family has always been the driving force in Escobedo’s life. They were there for him as a child when his uncle died in a car crash. They were there for him when he dislocated his shoulder in the NCAA tournament. Now, as he leads his team through a pandemic, they’re what steadies him.

Escobedo often tells his team to “embrace the chaos.”

There’s a daily inspirational quote on the board in the locker room. Escobedo tells his wrestlers he’s motivated to come in every day because he wants to help them grow as men. He continually tells sophomore Graham Rooks that he’s going to be an All-American.

Escobedo treats the wrestlers as if they were his own sons.

“He would do anything for his son,” IU assistant coach Jason Tsirtsis said.

During preseason workouts this fall, Escobedo woke up at 6:30 a.m. and made coffee. He checked his email. He put together his kids’ lunches of turkey, chips, yogurt and granola bars, among other items. He woke his kids up.

One day this fall, Saniyah didn’t want to go to school. Escobedo told Saniyah that her friends and teachers wanted to see her. After around 15 minutes of convincing, she agreed.

Related: [The unwavering voice of Angel Escobedo]

Growing up, Escobedo saw all the sacrifices his family made for him, driving to wrestling tournaments and putting food on the table. Now, he wants to do the same for his kids.

Now, before entering the school, they have the same conversation.

“Remember you have to be the hardest worker,” Escobedo said one morning this fall. “What else? Ask questions. What else? Listen to your teachers.”

“And never give up,” Malachi chimed in.

“Knuckles,” Escobedo said, reaching his fist out to Malachi and Saniyah. “Love you guys.”

He walks them to their classrooms every day. Malachi totes around an Avengers backpack while Saniyah has one from Frozen. Saniyah’s shirt reads “DREAMS DO COME TRUE.”

When Escobedo picks them up after school, he always asks them about their day.

“Malachi, do you remember what letter you learned today?” Escobedo said.

“C,” Malachi responded.

“C for what?” Escobedo said.

“Caterpillar,” Malachi called out.

“You say that everyday, dude,” Escobedo said with a laugh.

They proceeded to go through the alphabet. M for Malachi. S for Saniyah. G for grandpa.

“E for Angel,” Malachi said.

“Hey, you think that’s funny,” Escobedo said.

Malachi and Saniyah giggled with joy.

His mother’s scream is seared into his memory.

The coroner knocked on the Escobedo residence late at night. It wasn’t unusual for there to be trespassers around their Gary, Indiana, home. Sometimes people would try to break in.

At first, no one responded to the knock late in the night. Not 8-year-old Escobedo. Not his grandparents. Not his mother. Not his cousins.

The noise continued. That’s when he heard the scream. It pierced through the house. Now, if his wife yells, it takes Escobedo back to that moment.

The noise jarred young Escobedo, who was curled up in bed. His mother jumped into his grandmother’s arms sobbing. Everyone cried. They learned that his Uncle Esquiel wouldn’t be coming home again.

Uncle Esquiel had gone out to a bar earlier that night. One of his friends got into an argument, which led to a car chase. The vehicle Uncle Esquiel was in ran into a ditch.

Uncle Esquiel had lived with Escobedo for a period of time. Growing up, Escobedo stayed in his grandparents house with his single mother, cousins and uncles. There were 14 relatives living in the house at one point. Others lived nearby. Escobedo didn’t get his own bedroom until he was a senior in high school.

Later that night, a friend who had been in the car with Uncle Esquiel arrived at the house. His clothes were cut and covered with dirt.

“I’m so sorry,” he kept saying. “I’m so sorry.”

“Please forgive me. It’s all my fault.”

Escobedo’s grandmother didn’t stop crying. His mother rarely spoke. The family remained in the living room, hour after hour, the lights illuminating the house through the darkness. They wanted to know if Uncle Esquiel had been in pain.

Escobedo tried to grapple with what death meant. He was too young to fully understand it. I’m not going to see him anymore, he thought to himself.

Uncle Esquiel got the family invested in Catholicism. Wrestling had also been a huge part of Uncle Esquiel’s life, and he helped introduce it to Escobedo. He drove Escobedo and his five cousins to tournaments. He’d always playfully rough up Escobedo.

In the weeks following his death, wrestling wasn’t in the family’s minds. Family members came to the house everyday. They went to a funeral at the church. Escobedo and his cousins carried the casket. They scooped dirt onto the coffin before Uncle Esquiel was buried.

Eventually, Escobedo and his cousins started wrestling again. They spoke about Esquiel before practice as a reminder of his influence.

“Not to forget about him, but to keep moving forward because that’s probably what he would want anyway,” Esquiel’s brother David said last year.

“For us to keep going.”

There was no sofa in Uncle David’s living room. No coffee table or rug. No television. Just a black wrestling mat, stretching from wall to wall with a light cascading down. Oven mitts were wedged between the wall and the mat so the wall wouldn’t be damaged.

Uncle David cut posters from wrestling magazines and plastered them around the room. The pictures displayed wrestling moves: single leg takedowns, double leg takedowns and fireman’s carries. There was a number next to each one, denoting how many times they had to be completed.

That’s where Escobedo and his five cousins would be after school on Mondays, Wednesdays and Thursdays. Before they could play outside, they spent time in the wrestling room.

David drilled the group, helping the young wrestlers sharpen different techniques around the room. Every move had to be completed with the left and right foot. If it wasn’t correct, they did it again.

“It seemed like an eternity,” Escobedo said.

David quickly saw the potential in Escobedo. He was quick and smooth. But Escobedo was the youngest of the group and would always get picked on.

When the whole family would get together during the holidays, it was almost a ritual for the kids to break out into a wrestling frenzy. They would start talking about wrestling and, on cue, the older family members would move to the side, scooping up any valuables with them.

Then, the children would try to take each other down. Picture frames flew. Tables bent. Glasses were launched. Escobedo would get pummeled by the older girls.

“They’d always kick my butt,” Escobedo said.

Wrestling acted as a distraction to the streets that took Uncle Esquiel. Gary was dubbed the murder captial of the nation in the 1990s, shortly after Escobedo was born. Escobedo’s grandmother, who immigrated from Mexico, moved to Indiana after living in Texas.

“Bullets fly everywhere,” David said. “When the sun went down, you had to be in.”

Escobedo and his cousins would often play manhunt, a version of hide and seek. While they tore around the house, a helicopter searching for an actual suspect hovered overhead. A spotlight splashed down, winding from an alley to the Escobedo residence and around the neighborhood.

If a car was slowly rolling down the street, the kids yelled “drive by” and dove into the bushes. When Escobedo was 10 or 11, a woman was hit by a car and killed right in front of them.

Escobedo stopped buying new bikes because they kept getting stolen. One time, he was gifted a go cart. He rode it once.

“It was like heaven,” Escobedo said. “It was unreal.”

The next day, it was gone.

He wanted to find whoever took it and wrestle them.

They sometimes only ate tortillas and butter for dinner. Fried bologna was also a staple. But his grandmother ensured they didn’t go to bed hungry, despite how little there was in the pantry.

Eventually, his five older cousins emerged from the environment, all becoming Division I wrestlers. At the same time, Escobedo turned into one of the best wrestlers in the country, finishing high school as the only four-time state champion in the family and heading to IU to continue his career.

“It’s chaos, but that’s all I know,” Escobedo said. “To me, that’s almost like it being calm.”

This year, IU wrestling is amid a chaos of its own.

The Hoosiers will open its season two months late on Jan. 10. Some of his wrestlers have been struggling with the lack of structure, online classes and wrestling being taken away. Now, they’re tested six days a week for COVID-19.

“Life’s hard and it doesn’t get any easier, it only gets harder,” Escobedo said. “How can I build men that are going to be prepared for that, when life gets really, really hard. You have to learn how to keep going.”

Escobedo’s shoulder popped right out of the socket. He immediately knew something was wrong. It was double overtime in the 125-pound quarterfinals of the 2008 NCAA National Championships. Escobedo was face first on the mat, rolling in pain.

In his freshman season at IU the year prior, he finished fourth. Now, he was three wins away from a national championship with a dislocated left shoulder.

The trainer rushed out onto the mat and kneeled next to Escobedo. Within the first minute, his shoulder popped back into place. The normal recovery time for the injury was 12-16 weeks. He later learned he tore his labrum, too.

“I’m going to have to be dead before I walk off of this mat,” Escobedo said.

Once the match resumed in the final segment of overtime, it only took Escobedo 10 seconds to escape. With his shoulder glued to his side, he corkscrewed his body, pressing his opponent's head down and slipping out of his reach. He earned one point, securing him the victory.

The semifinals were that same night. Escobedo had a painkiller injection. He iced his shoulder. He worked on his range of motion.

A black brace was wrapped around his left arm for the match. As the clock ticked down to one minute left in the bout he was trailing 1-0, but Escobedo swung his leg behind his opponent and drove him into the mat, surging ahead for a 4-1 win.

His worries kept him up that night. He thought about his game plan and his shoulder.

“You want to control everything, but in reality you’re not in control,” Escobedo said.

He weighed in early on the morning of the finals. Later, Escobedo’s mom came into his hotel room. She told him how proud she was. She prayed that he would wrestle to the best of his ability. That his shoulder would hold up.

The Scottrade Center in St. Louis has a capacity of more than 18,000. It was nearly full, and the match was broadcast on ESPN. Escobedo didn’t hear the fans. He wasn’t nervous. He wasn’t worried about his shoulder.

Escobedo had been competing with his cousins his whole life. Back in David’s wrestling room. Back during the holidays when he’d get beaten up. To him, this was no different.

More than 30 family members were there, including his mom, his cousins and Uncle David.

“It felt like I was meant to be there,” Escobedo said.

Thirty seconds into the final period, Escobedo escaped and took a 3-2 lead. With ten seconds left and leading 5-3, all Escobedo had to do was stay on his feet. But he saw an opening and flattened his opponent onto his back.

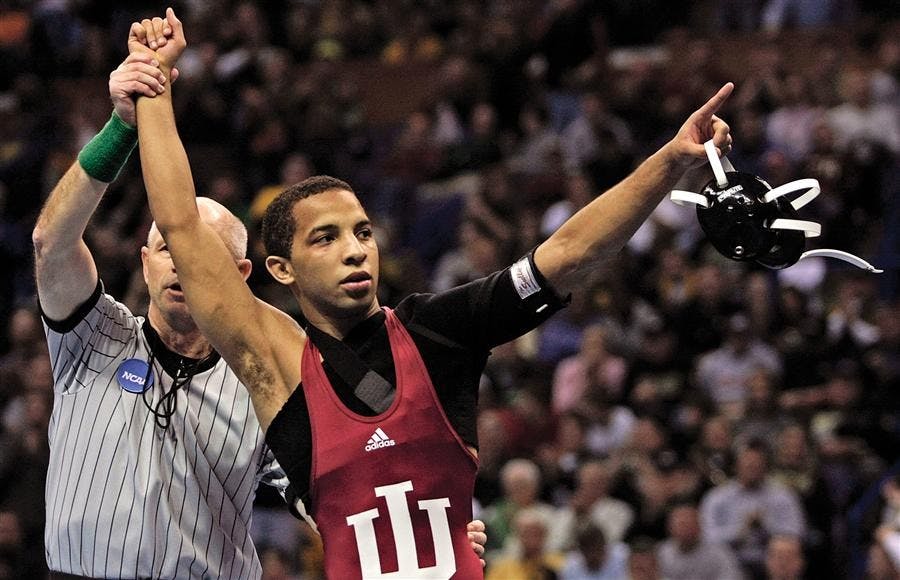

Escobedo popped up and pointed two fingers into the air. He flexed his biceps. He circled the mat and pounded his chest twice.

“An angel goes to the heavens,” the announcer said.

As the referee raised his arm in the air, Escobedo pointed to his family in the crowd. To his mom. To his cousins. To Uncle David.

In their hands, they waived homemade paper angel wings.

They raised them to the heavens.

If Escobedo doesn’t pick his kids up from school, they patiently wait for him to come home. They sprint to the door as soon as it opens.

“Daddy’s home,” Malachi or Escobedo’s wife Pauli calls out.

After a day of work, Escobedo plays with his kids. In the fall, they watched a pirate show on Nickelodeon. Escobedo pulled out a sheet of blank paper and drew a treasure map. He outlined the couch and TV and dotted a line leading to an X where a toy is hidden. They followed the path to the prize. Sometimes, they got lost and he had to help them.

If Escobedo is watching wrestling, they’re with him. If he has a recruiting call, they try to knock down the door. When they’re on break from school, they Facetime him in between practices. Malachi is already learning wrestling moves from his champion father.

When they all sit down for dinner, Saniyah says a prayer. Malachi pleads with his father to finish his meal so they can play more.

“He just refuses to let there be something that he could do better as a father,” Pauli said.

Escobedo and Pauli make it a race between Malachi and Saniyah to see who can get ready for bed the fastest. Escobedo reads bedtime stories to their youngest, Zoe. One of her favorites is “Daddy Loves Me!” Escobedo tickles her tiny feet during the story.

Then, Escobedo makes up bedtime stories for Malachi and Saniyah. It’s usually a winding mystical tale with Malachi and Saniyah as superheroes. They’re tasked with saving the world. One night, Pauli made up a story. Malachi said it wasn’t as good as his dad’s.

Escobedo lays there with them. Malachi is snuggled under a Spider-Man or Chicago Bears blanket. Saniyah’s bed is all pink with stuffed unicorns. Superhero costumes hang on the walls.

Escobedo stays until they fall asleep.

“Even when I was younger growing up, I remember thinking that if I ever become a dad, I want to be something that I didn’t have,” Escobedo said. “That’s my motivation. I make the most of the moment when I’m with them, just so when they become older they can always remember that I was there.”

There are still reminders of Escobedo’s youth around his house. Malachi has Escobedo’s old Hot Wheels cars. There’s a picture of Escobedo on his wedding day with his grandfather.

Whenever the family has gatherings in Indiana, Escobedo makes an effort to attend. The home screen on Escobedo’s phone is him with his kids and wife.

There’s one word inked on Escobedo’s upper chest that puts his life into perspective. He sees it in the mornings when he gets dressed. He sees it at night when he takes a shower. When he wears a V-neck shirt, his kids ask him what it means.

“I guess they forget,” Escobedo said. “So they keep asking again.”

Then he tells them.

Familia.