When Michael Penix stretched the ball barely across the goal line against then-No. 8 Penn State, giving IU a long-awaited upset victory, Harry Crider thought he’d look up to see thousands of fans storming the field. He thought he’d join night-long parties on Kirkwood Avenue.

Instead, the NFL draft-bound offensive lineman just saw empty bleachers. After Penix barely reached the ball over the goal line, giving IU a historic win over Penn State on Oct. 24 to begin the 2020 season, Crider drove his Jeep Renegade home from the stadium alongside a few dozen maskless students in the parking lot.

“Just go back to your solitude at your own apartment and wake up and go back to work the next day,” Crider said. “You just wonder how great it could have been around Bloomington with students getting more involved.”

IU had its best year in decades in a season that almost didn’t happen because of the coronavirus pandemic. The team finished with a 6-1 regular season record before losing to the University of Mississippi in the Outback Bowl on Jan. 2. The year featured program-defining wins over Penn State, Michigan and Wisconsin — the first time IU ever beat all three teams in the same season. IU ranked 12th in the final AP Top 25 poll.

But no fans were present to watch IU play before the Outback Bowl. Practices occurred entirely behind closed doors, a departure from previous years when media was allowed at fall camp. What happened inside the tunnels of Memorial Stadium stayed there.

During the summer, IU posted occasional press releases with testing data for the entire IU athletics program. Once the football season began, the updates stopped. Lists of inactive players ahead of each game did not specify whether a player was injured or ill, straying from norms of previous years where players’ injuries were specified.

But after the program had very few COVID-19 cases during the majority of the season, fans and some players alike were surprised when IU suddenly shut down its facilities Dec. 8, 2020. Nearly 30 players tested positive for COVID-19 during the team’s late-season outbreak.

“Nothing really kept us from playing until the second to last game,” said senior Jerome Johnson, an NFL Draft-bound defensive tackle. “I think that was just out of our control. It was bound to happen at some point.”

Throughout the season, players were tested daily and some were moved to hotels to avoid exposure. They received extra testing for potential long-term effects on their heart and lungs.

Four players departing the IU program — whether for the NFL draft or the transfer portal — spoke to the Indiana Daily Student to discuss the testing practices and rush to play despite several players not having fully recovered from the virus that has taken the lives of over 440,000 Americans.

Like every major college football program, IU learned how to handle a pandemic on the fly. And at IU, that meant pulling off a historic winning season while grappling with how to keep players safe from the coronavirus.

The rules were strict, and at first, that was overwhelming to Jordan Jakes, a redshirt freshman wide receiver who left IU via transfer after the season.

After months of debate, the Big Ten ultimately announced Sept. 16 that football games would resume in October. That came with a detailed COVID-19 response plan from the conference, including a requirement of daily testing.

Crider said daily testing made him feel more comfortable to play, even though he never considered opting out of the season.

“When our season first got canceled, I was still gonna plan on coming back,” Crider said. “But I was in, no matter what. I trusted the systems.”

The Big Ten also mandated players be tested for potential heart or lung damage if they contracted the virus. The risk for developing myocarditis — an inflammation of the heart which decreases its ability to pump blood — was especially concerning for the conference after a Penn State doctor found 30-35% of players in the Big Ten had myocarditis symptoms. All players who tested positive had to miss 21 days, including their 10-day isolation period and testing for harmful aftereffects.

The Big Ten wanted to create a bubble for each team. Players weren’t allowed to go out for anything other than picking up food or seeing a teammate. Johnson said he does not think any player violated that rule, but only an honor code enforced it.

Players weren’t allowed to see people outside of the program, including their families.

Australia native and NFL draft-bound punter Haydon Whitehead hasn’t seen his family in a little more than a year. But Whitehead never considered opting out, and said he didn’t know of many considering it.

“I think we all wanted to play, not only football in general, but I think we wanted to play together as a team,” Whitehead said. “I definitely say there was a drive there in general to want to play together and build off the 2019 season that we had.”

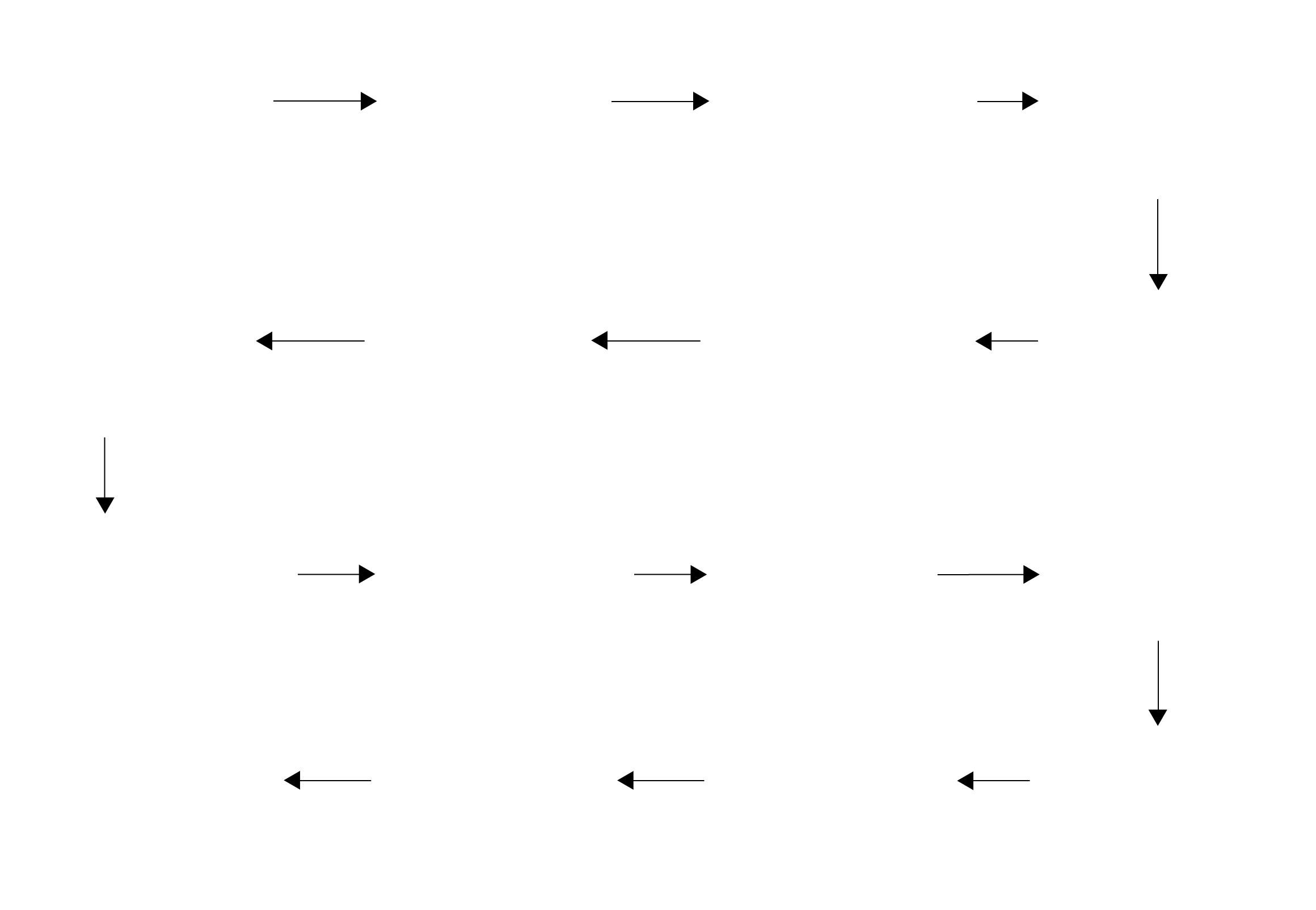

Players woke up around 6 a.m. every day for a self-administered nasal swab test between 7 a.m. and 8 a.m. at the football facility.

At first, Jakes said he got headaches from the swab poking deep inside his nose.

After their tests, players went into the locker room to get dressed for practice. Whitehead said IU’s staff effectively spaced out players as they entered the locker room and had them complete their tests in small groups.

But that meant players spent time with each other, indoors, before knowing their results. Two players who spoke to the Indiana Daily Student for this story said there were instances when a player they were near was pulled out of the locker room or a team meeting because of a positive test result.

A team spokesperson declined to comment on the record on testing practices and potential false results.

Players who tested negative would keep their masks on and move to a team meeting. Soon after, they took the field for practice where players did not consistently wear masks underneath their helmets, as photos from this season’s practices show.

The days blended together. Coronavirus restrictions meant that every day was the same, without in-person classes and parties and holidays. The schedule was uniform and left no room for players to go out or have any break from football. Jakes said he and others used the coaching staff’s mantras for each day of practice including “Mindset Monday” or “Takeaway Tuesday” as the only reminder of what day it actually was.

After practice and classes, most players relaxed playing video games online with their teammates, Jakes said. They played Madden, Call of Duty and Rocket League. Whitehead used the time to watch extra game film. Johnson binge-watched TikTok. Crider played Beatles and Nirvana music on his guitar and watched movie marathons, including classic movies he’d never seen before. The players’ options for entertainment were limited, and Crider said the time got boring.

But Jakes called football his job, and he said that was more important than missing a night out to party. He said he never got a chance to bond with his teammates like he did during the pandemic.

It’s not like he had a choice. They were the only people he could be around.

Johnson was surprised when he tested positive for the coronavirus. The team had stopped practicing Dec. 8, 2020, because of a COVID-19 outbreak, and the Purdue game — originally set for that weekend — had just been called off.

He said he hadn’t done anything outside of his home. So when he learned he tested positive, with no symptoms, he isolated in his room, wondering how he’d become a part of the late season outbreak too.

When a football player tested positive, the team moved their roommates to a new location. Most football players have roommates, but they are all just other players on the team. Crider had to relocate in the middle of the season when one of his roommates tested positive. He was moved to a hotel for 10-days while his roommate was isolated in their apartment. Crider called that a mini-vacation because he got new scenery for a few days.

Johnson said he didn’t know of any player who broke the team’s COVID-19 protocol, so many players were shocked when an outbreak started so fast. Johnson said with so many other teams shutting down, it was just a matter of time before IU had to.

Johnson finished his MRIs and heart testing in time to return to practice for the Outback Bowl, set to be played Jan. 2. The team resumed practice on Dec. 21, 2020. He said he didn’t feel rushed back, but he did not feel 100%. He said the coaches supported him whether or not he could play in the bowl game. Johnson had no issues with his breathing or his heart, but he only had a week-and-a-half to return to practice.

He said he remembers getting tired much quicker than usual during the game.

“I think for the most part the tempo was definitely different from what I’m used to,” Johnson said.

The tempo, Johnson said, both refers to how fast Ole Miss plays and to how he didn’t feel at full strength to keep up.

Jakes said he felt players who were sick didn’t have enough time to practice before the Outback Bowl. They had to go from not practicing during the outbreak to being ready to play a bowl game in two weeks.

“The preparation wasn’t the same,” Jakes said. “I feel that if we had a real preparation for the bowl game, the outcome would have been different.”

The four players who spoke to the IDS for this story said they were glad they chose to play this season. They were part of history — both the success on the field and the unprecedented circumstances off of it.

And being part of a historic winning season meant taking on historic risks.