It’s long past time to learn about the Chicago headquarters of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party — even more so since it’s Black History Month. Last summer’s Black Lives Matter movement caused increased allyship and exposed the need for performative allyship to stop.

To learn how to best be an ally, look to the Rainbow Coalition, a radical, multiracial coalition based in Chicago. From them, we can learn what it means to work with vision, bridge divides and get work done that tangibly helps communities.

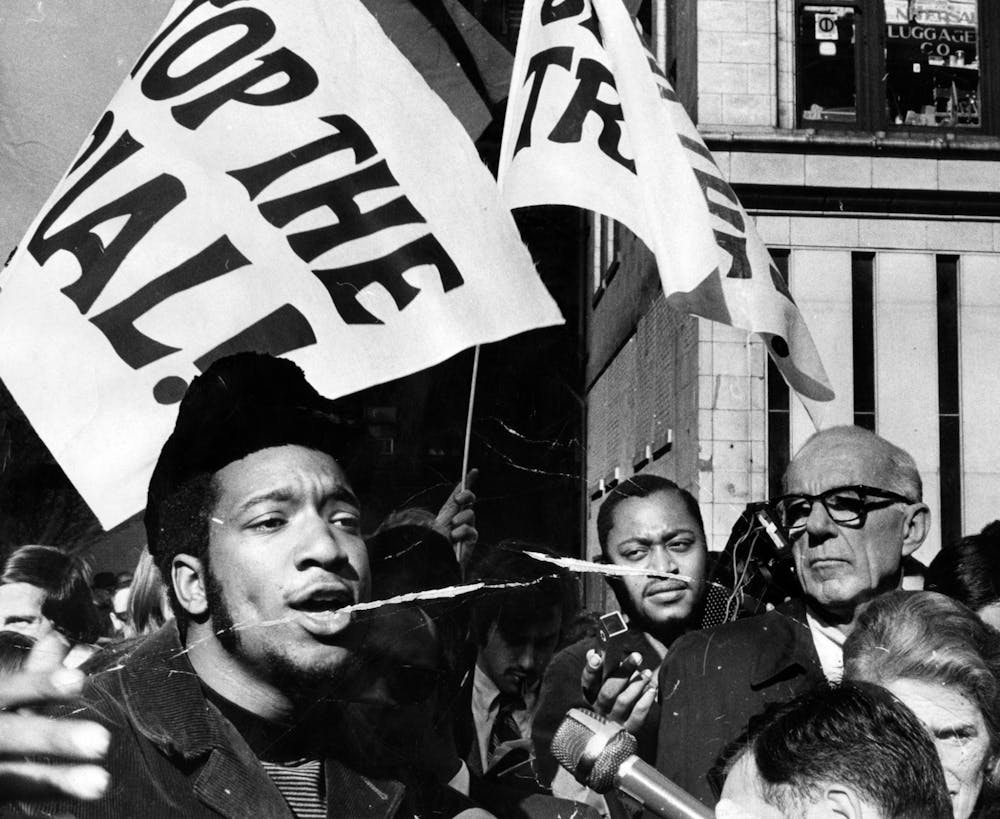

“Judas and the Black Messiah,” a film about Black Panther Deputy Chairman Fred Hampton and the informant charged to infiltrate the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party, premiers Feb. 12 in theatres and on HBO Max.

The Rainbow Coalition still lives on in large, city chapters and on campuses — including ours.

Jakobi Williams, an IU professor of African American and African Diaspora studies and history and the author of “From the Bullet to the Ballot: The Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party and Racial Coalition Politics in Chicago,” said the Rainbow Coalition was the brainchild of the Black Panther Party.

The Rainbow Coalition was a progressive, socialist movement that included the Black Panthers and a Puerto Rican gang-turned-human-rights organization called the Young Lords. Joining them was a white Appalachian migrant, leftist organization called the Young Patriots.

The coalition included Black Panther members Bobby Lee and Fred Hampton along with Young Lords founder José “Cha Cha” Jiménez and Young Patriots leader William “Preacherman” Fesperman. It eventually grew to include other Latino, Asian American, Native American and student organizations among others.

The Rainbow Coalition did not organize around colorblindness and non-confrontational political ideals.

“Chicago then, and still is today, the most racially, residentially segregated city in America,” Williams said.

According to South Side Weekly journalist Jacqueline Serrato, redlining, the systemic manner in which housing and services were segregated and denied to racial undesirables, was violently enforced by white street gangs. This was just one of many racial issues in Chicago.

“Fred Hampton and Bob Lee were able to transcend those so-called differences to bring these people together under the rubric of class solidarity,” Williams said.

They united to deal with poverty, gentrification, police brutality and political disempowerment.

Williams said the coalition saw itself as a continuation of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr 's Poor People’s Campaign, a democratic socialist effort that sought economic justice for poor people across backgrounds.

Survival programs, which the Panthers established to help meet the needs defined in their Ten Point Platform, were instrumental in the Coalition's work.

According to Serrato, these programs included the free breakfast program, free health clinics, day care centers and other social service programs. The Panthers helped other organizations establish programs in their communities, and these efforts were primarily spearheaded by women.

Some continue to be implemented by our government today, most notably the School Breakfast Program.

Along with embracing radical politics and emphasizing community programming, The Rainbow Coalition rejected paternalistic forms of allyship that meant others would come into communities as apparent saviors, impose solutions, and dominate leadership.

Williams said Hampton and Lee asserted “that we're working together in solidarity, but we're not trying to run your communities. So you guys advocate for whatever you think is important for your communities, and then when you’re ready to move forward, you contact us and we show up in support."

As we look at allyship today, it’s important to note the Rainbow Coalition did not come together for diluted ideas of diversity and representation.

They came together because of explicit and joint political goals. They did not dominate conversations of change, nor the communities being changed. They worked with each other, government organizations, and lawyers to bring change as quickly as possible.

Superficial reforms and demonstrations were not — and are not — enough. We need to have specific political vision, engage in community organizing, address policy directly, and work to break down oppressive systems systematically.

As we get ready to watch “Judas and the Black Messiah,” we should read and learn this history for ourselves. And when it’s time, get down and do the work.